Case Presentation

Case Presentation – Spring 2020

NHGUC with Schistosoma sp.

Written by: Alessandro Marotta, Student, Cleveland Clinic School of Cytotechnology, Cleveland, Ohio

Patient age: 28-year-old male

Specimen type: ThinPrep® Non-Gyn, Urine

Patient history: Gross hematuria in the past that becomes worse with lifting. While in Nairobi, patient states that he had been treated with “pills”. CT scan displays 2 bladder mural nodules. Treatment with Praziquantel prescribed.

Cytologic diagnosis: Negative for high grade urothelial carcinoma with Schistosoma sp.

Case provided by: This case generously donated by Associated Medical Professionals, Syracuse, NY.

NHGUC with Schistosoma Sp.

Etiology:

Schistosomiasis is an infectious disease where parasitic worms called blood flukes or trematodes of the Schistosoma genus undergoes a life cycle in humans.1 Their environment is in contaminated and infested waters from tropical and subtropical regions.1 Infection occurs when larval forms released by freshwater snails penetrate the skin.1,4 Once in the body, the larvae will grow into their adult forms and females produce eggs within the blood vessels.1,2 Some of these eggs exit via feces or urine but others remain embedded in body tissues, triggering immune reactions and eventual damage to organs.1 Transmission occurs when these infected patients utilize the water source during agricultural, recreation, domestic and any occupational activities.1

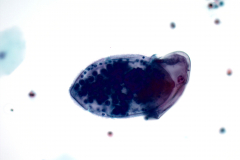

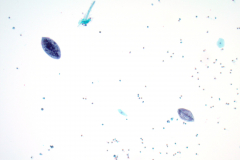

At this part of the cycle, the organism is categorized as diagnostic because the eggs are initially deposited in the portal and perivesical systems. 2 The adults, after infecting their hosts, move towards the intestines where they lay eggs. The ova eventually reach ureters and bladder before being eliminated by urine.2 When they hatch, they are called miracidia.2

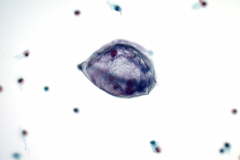

The case shows an example of a specific genus of Schistosoma, the Schistosoma haematobium, which is found in the bladder. The egg is characterized as large sized (about 110 – 170 micrometers long and 40 – 70 micrometers wide) and has a conspicuous, terminal spine.10 Some miracidia that hatched from the eggs were also present in the slide.

Clinical Features:

During a urogenital infection, there are general signs and symptoms including hematuria, fibrosis of the bladder and ureters as well as kidney damage.1,3,4 Women can get genital lesions, vaginal bleeding and nodules in the vulva and deal with painful intercourse.1 Men are at higher risk for developing squamous cell carcinoma.5

An intestinal infection develops abdominal pain, diarrhea and bloody stool.1 Children infected by the trematodes tend to develop anemia and a stunt in their growth.1

The patient is a 28-year-old male who had previous gross hematuria. The CT scan showed two bladder mural nodules.

Treatment & Prognosis:

Currently, there are no vaccines. The drug Praziquantel is used for treatment on a large-scale population.3 However, the timing of infection is critical as the drug is most effective with adult worms that will allow antibodies to form in response to the parasite.3 Travelers should take this medication about 6 – 8 weeks after last exposure to contaminated water.3 A single course of treatment is effective but patients with weaker immune systems need about 2 – 4 weeks.3 Dosage is about 40 – 60 mg/kg per day orally divided in 2 or 3 doses throughout the day.3

Malignancies associated with Schistosoma haematobium infection is endemic within the regions of North Africa and the Middle East.5 The Schistosoma-induced neoplasms is responsible for 20 – 30% of all bladder malignancies.5 The most common malignancy is squamous cell carcinoma and they are usually well or moderately differentiated but prognosis is more difficult if the carcinoma is poorly differentiated.5

Cytology:

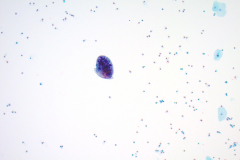

The voided urine specimen was processed as a ThinPrep® slide and was diagnosed as negative for high-grade urothelial carcinoma (NHGUC) based on the criteria established by the Paris System. NHGUC includes benign or reactive urothelial, glandular and squamous cells.5 There may be some urothelial tissue fragments or sheets and clusters, viral cytopathic effects, as well as post-therapy conditions.5

The superficial urothelial cells tend to be in convex or scalloped shapes with abundant or foamy cytoplasm.5 The nuclei can be bi- or multinucleated in a centric pattern with smooth nuclear membranes.5 Chromatin pattern is fine with the occasional nucleoli along with a low N/C ratio.5

Intermediate urothelial cells are roughly the same size as superficials but with lesser cytoplasm and decreased vacuoles.5 The chromatin may appear coarser but the thin, smooth nuclear membranes along with a relatively uniform distribution keeps the diagnosis at benign.5

The case shows benign urothelial cells with normal nuclei along with scattered squamous cells containing pyknotic and vesicular nuclei. There are also inflammatory cells including eosinophils, lymphocytes and neutrophils. These types of cells are normal during an infection of Schistosomiasis because they are the immune response to a parasitic infection. Thus, a few reactive changes to the nuclei are also benign. However, too many changes to the nuclei may indicate atypical, suspicious or positive for squamous cell carcinoma with Schistosomiasis.

Differentials Diagnoses:

Other Schistosoma species

There are other species within the Schistosoma genus including: S. japonicum, S. mansoni, S. mekogni and S. intercalatum.10 Each of them carries unique features including, but not limited to, shape, size, spine, geographic distribution and how they are excreted.10

- S. mansoni are larger and have a lateral spine in comparison to S. hematobium with their terminal spines while they both contain mature miracidium.10 They can be found in some areas of South America, Caribbean, Africa and the Middle East.10

- S. japonicum are rounder and have inconspicuous spines compared to S. hematobium in an ovoid shape with a prominent spine at the posterior end.10 This group of species is more commonly found in the Far East.10

- S. mekogni are smaller than S. japonicum but are also round with an inconspicuous spine.10 They are found in Southeast Asia.10

- S. intercalatum is locally exclusive in central West Africa and are longer ovoid shape with a central bulge.10

Unlike S. hematobium, the other Schistosoma species are seen in stool. They can be asymptomatic or symptomatic including fever, cough, abdominal pain, diarrhea, hepatosplenomegaly and eosinophilia.10 Further infections may cause granulomas, fibrosis and other types of lesions depending on the species.10

Lung Fluke (Paragonimiasis)

The lung flukes of the Paragonimus genus shares its similarities and differences with the Schistosoma.7 These parasites lay eggs within lungs and are picked up from sputum sampling.7 They do not appear in the bladder, but instead are digested and defecated.7

The eggs of the Paragonimus also differ from Schistosoma haematobium both in size and unique features.9, 10 Schistosoma haematobium includes a terminal spine while the Paragonimus does not have any form of a spine.9, 10

Paragonimus requires a second intermediate host such as crabs or crayfish before they are consumed under inadequate conditions.7,8 These worms also infect other organs and tissues and can cause chest pain, dyspnea, fever, pleural effusions and pneumothorax.7

Symptoms and signs are like tuberculosis and treatments, such as Triclabendazole and Praziquantel, are both used to get rid of the infection.7

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (Primary)

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is one type of epithelial cancer that present as a primary within multiple body sites.6 SCC can metastasize to other locations and progress in stages. Nuclear criteria include: hyperchromasia, chunky chromatin, membrane irregularity, pleomorphism and prominent nucleoli.6 Cytoplasmic criteria include the following but not limited to: keratinization, denser cytoplasm, tadpole or spindle shaped and poorly-differentiated.6

It’s also important to make note that this cancer, as well as any non-urothelial carcinomas, are uncommon and a pure population of cells is imperative for diagnosis.5 In countries where Schistosoma is endemic, there are two types of primary squamous cell carcinoma within the urinary tract.5

Bilharzial squamous cell carcinoma has a high male to female ratio (5-6:1) and presents with painful/tender, palpable masses.5 These patients are the ones who have chronic Schistosoma haematobium infections along with necroturia or dead cells found in urine.5 This condition occurs by the sixth decade.5

The non-bilharzial squamous cell carcinoma does not involve the organism. Patients who have epithelial injuries such as: spinal cord injury, chronic inflammation or paraplegic tend to develop non-bilharzial SCC before the seventh decade of life. These patients present with painless hematuria as well as irritative symptoms.5

References: 1. World Health Organization. Schistosomiasis. Published April 17, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schistosomiasis 2. CDC. Parasites – Schistosomiasis. Reviewed August 14, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/schistosomiasis/biology.html 3. CDC. Resources for Health Professionals – Schistosomiasis. Reviewed April 11, 2018. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/schistosomiasis/health_professionals/index.html 4. Bellafiore S, et al. Schistosoma haematobium in Urine Cytology: Diagnosis Is Possible. Am J Med. 2018;131(3):e87-e88. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.09.041 5. Rosenthal DL, et al. The Paris System for Reporting Urinary Cytology. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2016. 6. Cibas ES and Ducatman BS. Cytology: Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2014. 7. World Health Organization. Paragonimiasis. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://www.who.int/foodborne_trematode_infections/paragonimiasis/en/ 8. CDC. Parasites – Paragonimiasis. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/paragonimus/biology.html 9. CDC. Paragonimiasis. Reviewed December 14, 2017. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/paragonimiasis/index.html 10. CDC. Schistosomiasis. Published December 14, 2017. Reviewed August 14, 2019. Accessed January 16, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/schistosomiasis/index.html