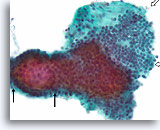

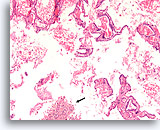

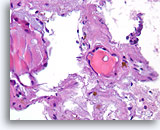

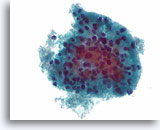

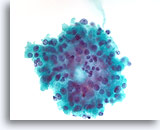

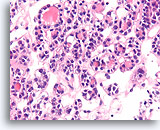

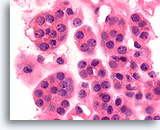

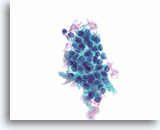

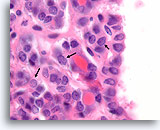

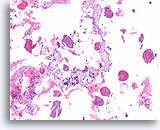

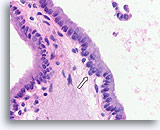

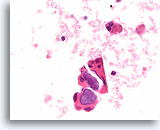

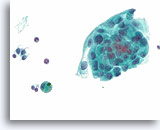

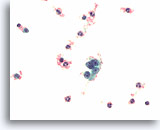

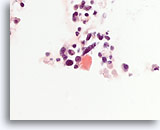

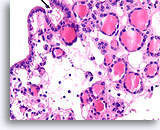

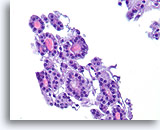

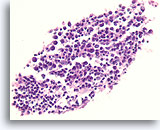

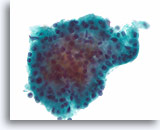

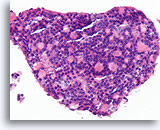

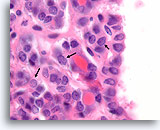

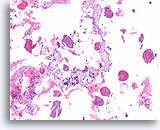

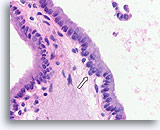

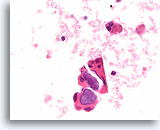

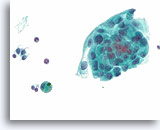

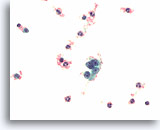

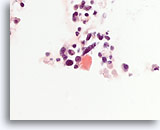

Figure 13

Benign, Hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The cell block corresponding to Figures 11-12 shows a clear admixture of micro and macrofollicles. Two features favor a benign nodule. The first is that the microfollicles show a flattened cytoplasm compared to the more robust-appearing macrofollicular cells (compare the height of the cytoplasm at the two arrows). A second feature is the variation in the appearance of the colloid from follicle to follicle. Note the edematous colloid in one follicle adjacent to a follicle with dense colloid (open arrows). Benign hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodules are anticipated to show heterogeneity, while follicular neoplasms are more monotonous.

40X

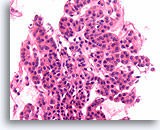

Figure 13

Benign, Hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The cell block corresponding to Figures 11-12 shows a clear admixture of micro and macrofollicles. Two features favor a benign nodule. The first is that the microfollicles show a flattened cytoplasm compared to the more robust-appearing macrofollicular cells (compare the height of the cytoplasm at the two arrows). A second feature is the variation in the appearance of the colloid from follicle to follicle. Note the edematous colloid in one follicle adjacent to a follicle with dense colloid (open arrows). Benign hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodules are anticipated to show heterogeneity, while follicular neoplasms are more monotonous.

40X

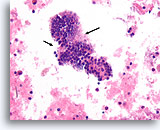

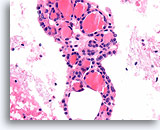

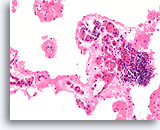

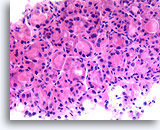

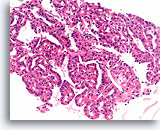

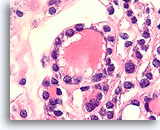

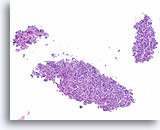

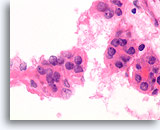

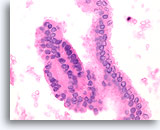

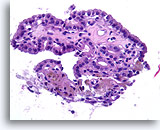

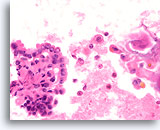

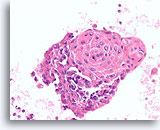

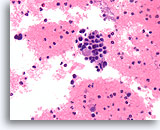

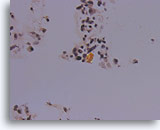

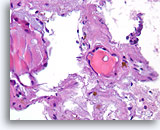

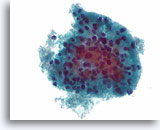

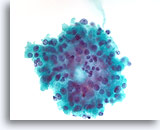

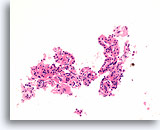

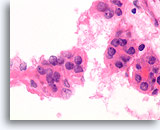

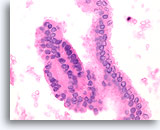

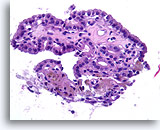

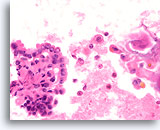

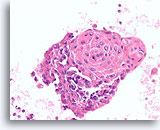

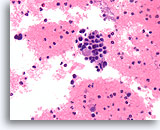

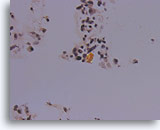

Figure 14

Benign, Hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Note the flattened cytoplasm in the microfollicles compared to the cuboidal to columnar cytoplasm of the macrofollicular epithelium at the upper left. Note also the watery colloid in one follicle (arrow) compared to the dense colloid in the microfollicles.

40X

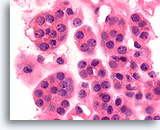

Figure 14

Benign, Hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Note the flattened cytoplasm in the microfollicles compared to the cuboidal to columnar cytoplasm of the macrofollicular epithelium at the upper left. Note also the watery colloid in one follicle (arrow) compared to the dense colloid in the microfollicles.

40X

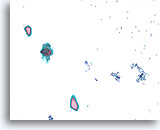

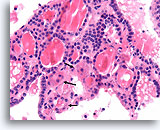

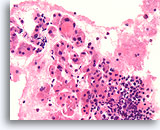

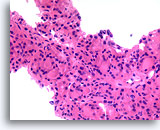

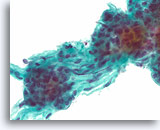

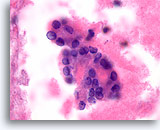

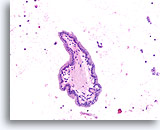

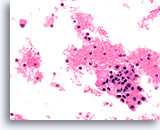

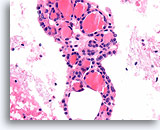

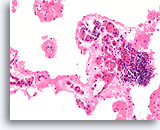

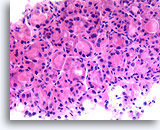

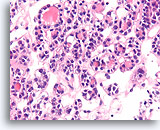

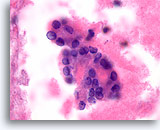

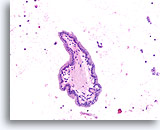

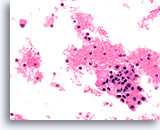

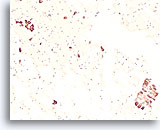

Figure 15

Benign, Hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Dense fibrous tissue (not actively desmoplastic) containing hemosiderin and markedly atrophic, flattened follicles are seen.

40X

Figure 15

Benign, Hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Dense fibrous tissue (not actively desmoplastic) containing hemosiderin and markedly atrophic, flattened follicles are seen.

40X

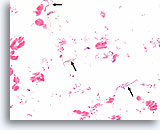

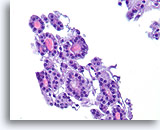

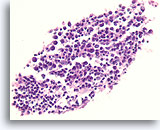

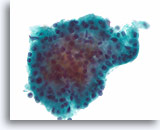

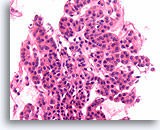

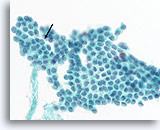

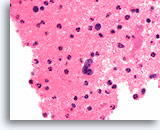

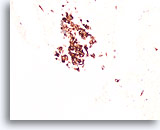

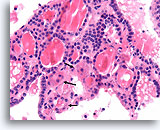

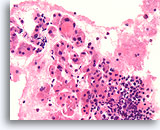

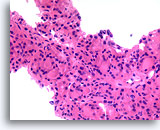

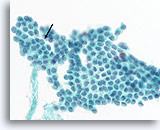

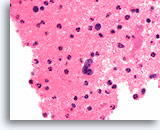

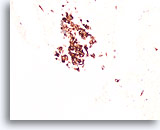

Figure 16

Benign, Hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Thin colloid at the lower left compared to the denser colloid in the microfollicles together with a flattened, atrophic appearance of the follicular cells in the microfollicles favor a benign hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule.

40X

Figure 16

Benign, Hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Thin colloid at the lower left compared to the denser colloid in the microfollicles together with a flattened, atrophic appearance of the follicular cells in the microfollicles favor a benign hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule.

40X

Figure 17

Benign, Hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The tissue architecture evident here illustrates the variability in the cytoplasm between neighboring follicles, with the follicles marked with arrows showing varying degrees of Hürthle cell change compared to the unmarked follicles.

40X

Figure 17

Benign, Hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The tissue architecture evident here illustrates the variability in the cytoplasm between neighboring follicles, with the follicles marked with arrows showing varying degrees of Hürthle cell change compared to the unmarked follicles.

40X

Figure 18

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The uniformity of the cytoplasm, the robust cuboidal epithelial cells, the microfollicular arrangement, the absence of hemosiderin, and the uniformity of the colloid favor a follicular neoplasm in this one field.

40X

Figure 18

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The uniformity of the cytoplasm, the robust cuboidal epithelial cells, the microfollicular arrangement, the absence of hemosiderin, and the uniformity of the colloid favor a follicular neoplasm in this one field.

40X

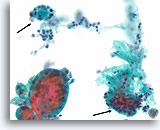

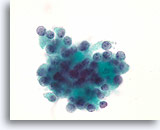

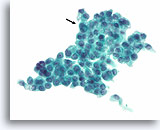

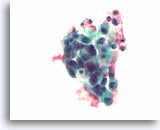

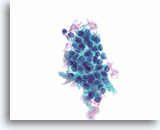

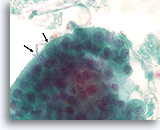

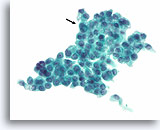

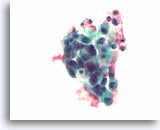

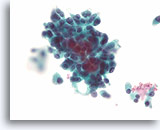

Figure 19

Cellular lesion, Cannot rule out follicular neoplasm (lymphocytic thyroiditis vs. Hürthle cell neoplasm), Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

A microfollicular arrangement of Hürthle cells is seen. A few lymphocytes are admixed with the epithelium favoring lymphocytic thyroiditis.

60X

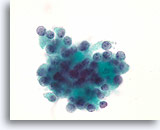

Figure 19

Cellular lesion, Cannot rule out follicular neoplasm (lymphocytic thyroiditis vs. Hürthle cell neoplasm), Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

A microfollicular arrangement of Hürthle cells is seen. A few lymphocytes are admixed with the epithelium favoring lymphocytic thyroiditis.

60X

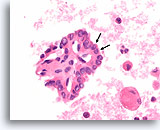

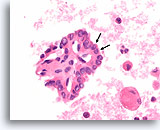

Figure 20

Benign, Lymphocytic thyroiditis, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This image from the case shown in Figure 19 shows a dense lymphocytic infiltrate with adjacent flattened microfollicles showing Hürthle cell change.

20X

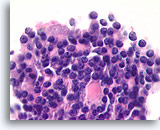

Figure 20

Benign, Lymphocytic thyroiditis, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This image from the case shown in Figure 19 shows a dense lymphocytic infiltrate with adjacent flattened microfollicles showing Hürthle cell change.

20X

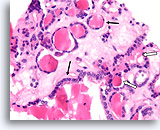

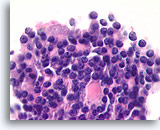

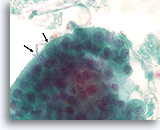

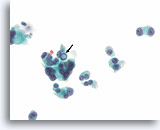

Figure 21

Benign, Lymphocytic thyroiditis, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

At higher magnification, the infiltration of the follicles with lymphocytes can be seen.

40X

Figure 21

Benign, Lymphocytic thyroiditis, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

At higher magnification, the infiltration of the follicles with lymphocytes can be seen.

40X

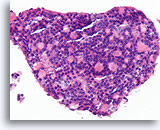

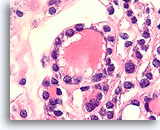

Figure 22

Benign, Lymphocytic thyroiditis, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A lymphoid germinal center is shown.

40X

Figure 22

Benign, Lymphocytic thyroiditis, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A lymphoid germinal center is shown.

40X

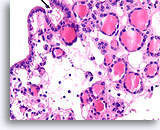

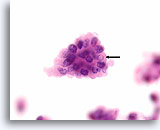

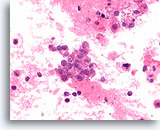

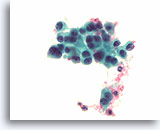

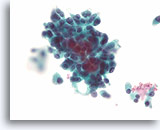

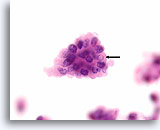

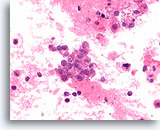

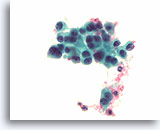

Figure 23

Cellular lesion, Cannot rule out follicular neoplasm (Hürthle cell neoplasm vs. Lymphocytic thyroiditis), Thyroid, ThinPrep®.

A microfollicular group of Hürthle cells with a few possible lymphocytes is present.

60X

Figure 23

Cellular lesion, Cannot rule out follicular neoplasm (Hürthle cell neoplasm vs. Lymphocytic thyroiditis), Thyroid, ThinPrep®.

A microfollicular group of Hürthle cells with a few possible lymphocytes is present.

60X

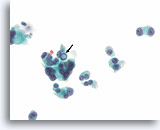

Figure 24

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This image from the case in Figure 23 shows the uniformity of the Hürthle cell population which, together with the robust cuboidal cytoplasm in microfollicles, favors a Hürthle cell neoplasm.

40X

Figure 24

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This image from the case in Figure 23 shows the uniformity of the Hürthle cell population which, together with the robust cuboidal cytoplasm in microfollicles, favors a Hürthle cell neoplasm.

40X

Figure 25

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The extent of the Hürthle cell change is too broad to be a reaction to any rare admixed lymphoid cells.

40X

Figure 25

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The extent of the Hürthle cell change is too broad to be a reaction to any rare admixed lymphoid cells.

40X

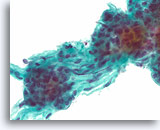

Figure 26

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

This case shows a uniform microfollicular arrangement of robust-appearing Hürthle cells without lymphocytes.

60X

Figure 26

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

This case shows a uniform microfollicular arrangement of robust-appearing Hürthle cells without lymphocytes.

60X

Figure 27

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

This crowded group consists of relatively uniform cells with dense, granular cytoplasm.

60X

Figure 27

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

This crowded group consists of relatively uniform cells with dense, granular cytoplasm.

60X

Figure 28

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This image from the same case in Figures 26-27 shows uniform Hürthle cell change, microfollicular arrangement and absence of lymphocytes.

20X

Figure 28

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This image from the same case in Figures 26-27 shows uniform Hürthle cell change, microfollicular arrangement and absence of lymphocytes.

20X

Figure 29

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Another area shows larger-sized fragment with a monotonous population spanning several hundred microns and favors the diagnosis of a neoplasm.

20X

Figure 29

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Another area shows larger-sized fragment with a monotonous population spanning several hundred microns and favors the diagnosis of a neoplasm.

20X

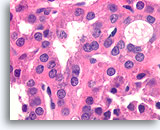

Figure 30

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Higher magnification shows the round nuclei and distinct chromatin particles of the Hürthle cells.

100X

Figure 30

Follicular neoplasm, Hürthle cell type, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Higher magnification shows the round nuclei and distinct chromatin particles of the Hürthle cells.

100X

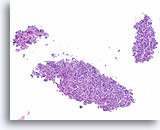

Figure 31

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

This low power view shows three groups with uniform microfollicles.

10X

Figure 31

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

This low power view shows three groups with uniform microfollicles.

10X

Figure 32

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This image from the case in Figure 31. Macrofollicles are seen, but no cystic change is present and the intervening abundant microfollicles are uniform.

10X

Figure 32

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This image from the case in Figure 31. Macrofollicles are seen, but no cystic change is present and the intervening abundant microfollicles are uniform.

10X

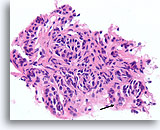

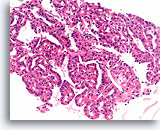

Figure 33

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A higher magnification shows the robust cuboidal follicles and slightly atypical but monotonous population of cells forming microfollicles.

40X

Figure 33

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A higher magnification shows the robust cuboidal follicles and slightly atypical but monotonous population of cells forming microfollicles.

40X

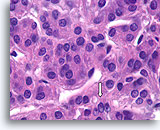

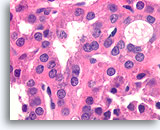

Figure 34

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The follicular cells have round nuclei with anisonucleosis and slightly coarse chromatin aggregates.

100X

Figure 34

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The follicular cells have round nuclei with anisonucleosis and slightly coarse chromatin aggregates.

100X

Figure 35

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Another case is shown, with uniform microfollicles.

20X

Figure 35

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Another case is shown, with uniform microfollicles.

20X

Figure 36

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Higher power shows round nuclei with slightly coarse chromatin.

60X

Figure 36

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Higher power shows round nuclei with slightly coarse chromatin.

60X

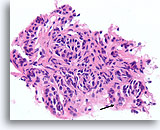

Figure 37

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A microbiopsy fragment from the same case in Figures 35-36 shows a monotonous microfollicular growth pattern. No hemosiderin or cystic degeneration is apparent.

10X

Figure 37

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A microbiopsy fragment from the same case in Figures 35-36 shows a monotonous microfollicular growth pattern. No hemosiderin or cystic degeneration is apparent.

10X

Figure 38

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Note the robust cuboidal cells that form monotonous microfollicles. No colloid is evident.

40X

Figure 38

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Note the robust cuboidal cells that form monotonous microfollicles. No colloid is evident.

40X

Figure 39

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

At higher magnification, the round, regular nuclei with slightly coarse chromatin aggregates are seen.

100X

Figure 39

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

At higher magnification, the round, regular nuclei with slightly coarse chromatin aggregates are seen.

100X

Figure 40

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

A different case from the preceding shows a monotonous population of follicular cells with a microfollicular arrangement and no hemosiderin.

20X

Figure 40

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

A different case from the preceding shows a monotonous population of follicular cells with a microfollicular arrangement and no hemosiderin.

20X

Figure 41

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Small, uniform, dense colloid fragments are contained in the microfollicular groups, and the follicular cells have similar morphology from group to group.

40X

Figure 41

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Small, uniform, dense colloid fragments are contained in the microfollicular groups, and the follicular cells have similar morphology from group to group.

40X

Figure 42

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

The nuclei of these follicular cells do not show features of papillary thyroid carcinoma. The nuclei are round, and chromatin is arranged in frequent non-linear aggregates.

100X

Figure 42

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

The nuclei of these follicular cells do not show features of papillary thyroid carcinoma. The nuclei are round, and chromatin is arranged in frequent non-linear aggregates.

100X

Figure 43

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This image from the case in Figures 40-42 shows a monotonous population with a microfollicular growth pattern, without hemosiderin or cystic change.

10X

Figure 43

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This image from the case in Figures 40-42 shows a monotonous population with a microfollicular growth pattern, without hemosiderin or cystic change.

10X

Figure 44

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Nuclei are round and uniform, with coarse chromatin. An ominous feature is the back-to-back, solid arrangement of the follicular cells, without an intervening basement membrane.

100X

Figure 44

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Nuclei are round and uniform, with coarse chromatin. An ominous feature is the back-to-back, solid arrangement of the follicular cells, without an intervening basement membrane.

100X

Figure 45

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Our unpublished observations suggest that the back to back growth pattern, reminiscent of cribriform ductal carcinoma in situ, is suggestive of the insular type of poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Indeed, the resection of this specimen showed insular carcinoma with widespread angio-invasion.

40X

Figure 45

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Our unpublished observations suggest that the back to back growth pattern, reminiscent of cribriform ductal carcinoma in situ, is suggestive of the insular type of poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Indeed, the resection of this specimen showed insular carcinoma with widespread angio-invasion.

40X

Figure 46

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A detached cluster of small blood vessels is staining positive for CD34 at the upper left. Note the absence of staining within the back-to-back group of follicular cells (arrow). The large-scale back-to-back growth without an intervening basement membrane/capillary network is essentially the diagnostic insular pattern recognized by surgical pathologists.

10X

Figure 46

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A detached cluster of small blood vessels is staining positive for CD34 at the upper left. Note the absence of staining within the back-to-back group of follicular cells (arrow). The large-scale back-to-back growth without an intervening basement membrane/capillary network is essentially the diagnostic insular pattern recognized by surgical pathologists.

10X

Figure 47

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

A solid-appearing growth pattern is seen without colloid.

60X

Figure 47

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

A solid-appearing growth pattern is seen without colloid.

60X

Figure 48

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Another similar “clonal-appearing” cluster, with similar nuclear and cytoplasmic features is seen.

60X

Figure 48

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Another similar “clonal-appearing” cluster, with similar nuclear and cytoplasmic features is seen.

60X

Figure 49

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This image from the case in Figures 47-48 shows a relatively cohesive, uniform, clonal-appearing population with microfollicular architecture, consistent with a neoplasm.

10X

Figure 49

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This image from the case in Figures 47-48 shows a relatively cohesive, uniform, clonal-appearing population with microfollicular architecture, consistent with a neoplasm.

10X

Figure 50

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The nuclei show focal chromatin clearing (arrow). This process is clearly neoplastic, but could it be follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma?

40X

Figure 50

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The nuclei show focal chromatin clearing (arrow). This process is clearly neoplastic, but could it be follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma?

40X

Figure 51

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

While most of the nuclei are round and show some coarse chromatin aggregates, a few thin nuclear grooves are present and some of the nuclei show fine chromatin (open arrow).

100X

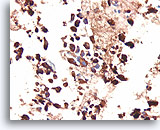

Figure 52

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

An immunostain for cytokeratin 19 is negative. While there are no definitive markers of papillary thyroid carcinoma, an absence of cytokeratin 19 is somewhat helpful in excluding papillary thyroid carcinoma. Reactive changes that can resemble papillary thyroid carcinoma are often positive for cytokeratin 19, so positive staining has to be interpreted carefully.

20X

Figure 52

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

An immunostain for cytokeratin 19 is negative. While there are no definitive markers of papillary thyroid carcinoma, an absence of cytokeratin 19 is somewhat helpful in excluding papillary thyroid carcinoma. Reactive changes that can resemble papillary thyroid carcinoma are often positive for cytokeratin 19, so positive staining has to be interpreted carefully.

20X

Figure 53

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A positive thyroglobulin stain can be helpful to exclude medullary thyroid carcinoma in a case that shows no evident colloid.

20X

Figure 53

Follicular neoplasm, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A positive thyroglobulin stain can be helpful to exclude medullary thyroid carcinoma in a case that shows no evident colloid.

20X

Figure 54

Suspicious for follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Multiple small dense colloid fragments are seen consistent with microfollicular architecture. At the edges of the fragment, nuclei show open chromatin, and slight irregularity in shape (arrow).

100X

Figure 54

Suspicious for follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Multiple small dense colloid fragments are seen consistent with microfollicular architecture. At the edges of the fragment, nuclei show open chromatin, and slight irregularity in shape (arrow).

100X

Figure 55

Suspicious for Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Compared to the follicular neoplasms shown in previous figures, the chromatin is less coarse in this microfollicular group, and slight anisonucleosis is present.

100X

Figure 55

Suspicious for Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Compared to the follicular neoplasms shown in previous figures, the chromatin is less coarse in this microfollicular group, and slight anisonucleosis is present.

100X

Figure 56

Suspicious for Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Pronounced nuclear envelope irregularity is present (arrow).

100X

Figure 56

Suspicious for Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Pronounced nuclear envelope irregularity is present (arrow).

100X

Figure 57

Suspicious for Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Low magnification of the case in Figures 54-56 shows numerous clonal-appearing fragments with a predominantly microfollicular architecture.

40X

Figure 57

Suspicious for Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Low magnification of the case in Figures 54-56 shows numerous clonal-appearing fragments with a predominantly microfollicular architecture.

40X

Figure 58

Suspicious for Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Two of the follicles at this magnification appear to be macrofollicular (at least 10 follicular cell diameters). No papillary structures are evident. Papillary thyroid carcinomas do not need to show papillary architecture and they can be macrofollicular. The defining feature of papillary thyroid carcinoma lies in the nuclear morphology, requiring higher magnification.

10X

Figure 58

Suspicious for Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Two of the follicles at this magnification appear to be macrofollicular (at least 10 follicular cell diameters). No papillary structures are evident. Papillary thyroid carcinomas do not need to show papillary architecture and they can be macrofollicular. The defining feature of papillary thyroid carcinoma lies in the nuclear morphology, requiring higher magnification.

10X

Figure 59

Suspicious for Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Very fine chromatin and slight nuclear envelope irregularity is present, suspicious for follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Note how fine linear arrays of chromatin (nuclei marked with arrows) are more easily seen than rounded aggregates of chromatin. The linear arrays represent very shallow nuclear envelope folds.

100X

Figure 59

Suspicious for Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Very fine chromatin and slight nuclear envelope irregularity is present, suspicious for follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Note how fine linear arrays of chromatin (nuclei marked with arrows) are more easily seen than rounded aggregates of chromatin. The linear arrays represent very shallow nuclear envelope folds.

100X

Figure 60

Suspicious for Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The dividing line between follicular-type and papillary-type epithelium is not yet well-defined. Histolologic sections of thyroid FNAs provide a common platform for surgical pathologists and cytopathologists to define criteria. The resection from this case was diagnosed as follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma.

100X

Figure 60

Suspicious for Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The dividing line between follicular-type and papillary-type epithelium is not yet well-defined. Histolologic sections of thyroid FNAs provide a common platform for surgical pathologists and cytopathologists to define criteria. The resection from this case was diagnosed as follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma.

100X

Figure 61

Suspicious for papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

A cluster with a microfollicular architecture and dense colloid shows nuclei with fine chromatin, ovoid shape, and occasional grooves. Hemosiderin is present, a finding that favors papillary thyroid carcinoma over a follicular-type neoplasm.

60X

Figure 61

Suspicious for papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

A cluster with a microfollicular architecture and dense colloid shows nuclei with fine chromatin, ovoid shape, and occasional grooves. Hemosiderin is present, a finding that favors papillary thyroid carcinoma over a follicular-type neoplasm.

60X

Figure 62

Suspicious for papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This high power image from the same case as Figure 61 shows similar features. Note the fine chromatin arranged in thin lines representing shallow folds of the nuclear envelope.

100X

Figure 62

Suspicious for papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This high power image from the same case as Figure 61 shows similar features. Note the fine chromatin arranged in thin lines representing shallow folds of the nuclear envelope.

100X

Figure 63

Suspicious for papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A cytokeratin 19 stain is positive, strongly supporting the suspicion of papillary thyroid carcinoma.

20X

Figure 62

Suspicious for papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A cytokeratin 19 stain is positive, strongly supporting the suspicion of papillary thyroid carcinoma.

20X

Figure 64

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

A sharply defined intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion (arrow), very fine chromatin texture, irregular nuclear contours, and ovoid nuclei are characteristic. Note the broad flat 2 dimensional sheet, indicative of a macrofollicular architecture which is common in papillary thyroid carcinomas.

60X

Figure 64

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

A sharply defined intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion (arrow), very fine chromatin texture, irregular nuclear contours, and ovoid nuclei are characteristic. Note the broad flat 2 dimensional sheet, indicative of a macrofollicular architecture which is common in papillary thyroid carcinomas.

60X

Figure 65

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The presence of abundant colloid does not exclude papillary thyroid carcinoma.

10X

Figure 65

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The presence of abundant colloid does not exclude papillary thyroid carcinoma.

10X

Figure 66

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The long strip on the right side is a macrofollicular grouping similar to that shown in Figure 64. Note the fine chromatin and nuclear envelope irregularity.

60X

Figure 66

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

The long strip on the right side is a macrofollicular grouping similar to that shown in Figure 64. Note the fine chromatin and nuclear envelope irregularity.

60X

Figure 67

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A sharply demarcated intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion (arrow), fine chromatin texture, and nuclear envelope irregularity are the most important features for diagnosing papillary thyroid carcinoma.

100X

Figure 67

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A sharply demarcated intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion (arrow), fine chromatin texture, and nuclear envelope irregularity are the most important features for diagnosing papillary thyroid carcinoma.

100X

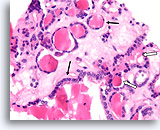

Figure 68

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Papillary structures may be present in both papillary thyroid carcinomas and benign hyperplastic nodules. The crowding of the nuclei is suggestive of papillary thyroid carcinoma.

20X

Figure 68

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Papillary structures may be present in both papillary thyroid carcinomas and benign hyperplastic nodules. The crowding of the nuclei is suggestive of papillary thyroid carcinoma.

20X

Figure 69

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A higher magnification of Figure 68 shows diagnostic features consisting of crowded nuclei with nuclear grooves, very fine chromatin, a rare intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion (open arrow), and a subtle loss of polarity in areas.

60X

Figure 69

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A higher magnification of Figure 68 shows diagnostic features consisting of crowded nuclei with nuclear grooves, very fine chromatin, a rare intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion (open arrow), and a subtle loss of polarity in areas.

60X

Figure 70

Benign, Hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Papillary structures without the nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma strongly favor a benign nodule. Compared to papillary thyroid carcinoma, the nuclei are round, evenly spaced, and have a uniform amount of apical cytoplasm. [6]

40X

Figure 70

Benign, Hyperplastic/adenomatoid nodule, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Papillary structures without the nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma strongly favor a benign nodule. Compared to papillary thyroid carcinoma, the nuclei are round, evenly spaced, and have a uniform amount of apical cytoplasm. [6]

40X

Figure 71

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Note the abnormal polarity of the nuclei (arrow) that also exhibit nuclear grooves, and fine chromatin.

100X

Figure 71

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Note the abnormal polarity of the nuclei (arrow) that also exhibit nuclear grooves, and fine chromatin.

100X

Figure 72

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Abnormal nuclear polarity in two adjacent cells (arrows) is seen in a papillary fragment, similar to that in Figure 71.

60X

Figure 72

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Abnormal nuclear polarity in two adjacent cells (arrows) is seen in a papillary fragment, similar to that in Figure 71.

60X

Figure 73

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Bluish calcified psammoma bodies are highly suggestive of papillary thyroid carcinoma but are not sufficient for a diagnosis.

60X

Figure 73

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Bluish calcified psammoma bodies are highly suggestive of papillary thyroid carcinoma but are not sufficient for a diagnosis.

60X

Figure 74

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Open chromatin, rare nuclear grooves, and subtle abnormal nuclear polarity are present. Note the cystic background – a common feature in papillary thyroid carcinoma.

60X

Figure 74

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Open chromatin, rare nuclear grooves, and subtle abnormal nuclear polarity are present. Note the cystic background – a common feature in papillary thyroid carcinoma.

60X

Figure 75

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Uniform empty-appearing cytoplasmic vacuoles are sometimes seen in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Typical nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma are present, with a prominent intranuclear inclusion (arrow).

60X

Figure 75

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Uniform empty-appearing cytoplasmic vacuoles are sometimes seen in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Typical nuclear features of papillary thyroid carcinoma are present, with a prominent intranuclear inclusion (arrow).

60X

Figure 76

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

The vacuolated cytoplasm can sometimes give the papillary thyroid carcinoma cells a histiocytoid appearance.

60X

Figure 76

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

The vacuolated cytoplasm can sometimes give the papillary thyroid carcinoma cells a histiocytoid appearance.

60X

Figure 77

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Histiocytoid carcinoma cells with uniform empty cytoplasmic vacuoles similar to those in Figure 76 are shown.

60X

Figure 77

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Histiocytoid carcinoma cells with uniform empty cytoplasmic vacuoles similar to those in Figure 76 are shown.

60X

Figure 78

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Squamous metaplasia is another common cytoplasmic change in papillary thyroid carcinoma.

60X

Figure 78

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Squamous metaplasia is another common cytoplasmic change in papillary thyroid carcinoma.

60X

Figure 79

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This group from the same case in Figure 78 shows similar, prominent squamous metaplasia.

40X

Figure 79

Papillary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This group from the same case in Figure 78 shows similar, prominent squamous metaplasia.

40X

Figure 80

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Mildly pleomorphic cells with eccentric nuclei are present with translucent, dense fragments of amyloid.

60X

Figure 80

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Mildly pleomorphic cells with eccentric nuclei are present with translucent, dense fragments of amyloid.

60X

Figure 81

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Slightly coarse chromatin, eccentric nuclei, and slight cell-to-cell variation in the nuclear morphology is present.

60X

Figure 81

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Slightly coarse chromatin, eccentric nuclei, and slight cell-to-cell variation in the nuclear morphology is present.

60X

Figure 82

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Typical coarse “salt and pepper” chromatin is present.

60X

Figure 82

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Typical coarse “salt and pepper” chromatin is present.

60X

Figure 83

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A solid growth pattern is present with a fragment of amyloid. Note the eccentric nuclei with a plasmacytoid appearance, and slight nuclear variability.

40X

Figure 83

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

A solid growth pattern is present with a fragment of amyloid. Note the eccentric nuclei with a plasmacytoid appearance, and slight nuclear variability.

40X

Figure 84

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Small aggregates of amyloid are present in a mildly pleomorphic population.

40X

Figure 84

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Small aggregates of amyloid are present in a mildly pleomorphic population.

40X

Figure 85

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

“Salt and pepper” chromatin similar to Figure 82 is shown.

60X

Figure 85

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

“Salt and pepper” chromatin similar to Figure 82 is shown.

60X

Figure 86

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This congo-red stain performed on the case shown in Figures 80-85 highlights a fragment of amyloid.

60X

Figure 86

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This congo-red stain performed on the case shown in Figures 80-85 highlights a fragment of amyloid.

60X

Figure 87

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Under polarized light, the congo red-stained amyloid shows the characteristic greenish birefringence.

40X

Figure 87

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Under polarized light, the congo red-stained amyloid shows the characteristic greenish birefringence.

40X

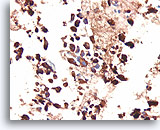

Figure 88

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

These groups from the case in Figures 80-86 stain positive for calcitonin.

20X

Figure 88

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

These groups from the case in Figures 80-86 stain positive for calcitonin.

20X

Figure 89

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Synaptophysin immunoreactivity is also present in medullary thyroid carcinoma.

20X

Figure 89

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

Synaptophysin immunoreactivity is also present in medullary thyroid carcinoma.

20X

Figure 90

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

A different case from the previous case shows a slightly more pleomorphic population that varies from plasmacytoid to focally spindled.

60X

Figure 90

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

A different case from the previous case shows a slightly more pleomorphic population that varies from plasmacytoid to focally spindled.

60X

Figure 91

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

An intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion is present in one of the cells of this mildly pleomorphic population.

60X

Figure 91

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

An intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion is present in one of the cells of this mildly pleomorphic population.

60X

Figure 92

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Spindle shaped tumor cells are also present.

40X

Figure 92

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, ThinPrep®.

Spindle shaped tumor cells are also present.

40X

Figure 93

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This same case as Figures 90-92 shows a strong positive immunostain for calcitonin.

40X

Figure 93

Medullary thyroid carcinoma, Thyroid FNA, Cell Block.

This same case as Figures 90-92 shows a strong positive immunostain for calcitonin.

40X