Case Presentation

Case Presentation – October 2021

Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma

Written by: Bryn Kelver, Student, Cleveland Clinic School of Cytotechnology, Cleveland, Ohio

Patient Age: 52-year-old female

Specimen Type: Left pleural fluid, ThinPrep® Non-Gyn, Traditional cell block

Patient History: Left flank pain. Family history of ovarian carcinoma.

Cytologic Diagnosis: Positive for malignant cells. Adenocarcinoma.

Biopsy / Pathologic Diagnosis: Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma.

Case provided by: Cleveland Clinic, regional Hospital, Mayfield Heights, Ohio

Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma

Etiology: Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (EHE) is a malignant, extremely rare vascular tumor originating from vascular pre-endothelial or endothelial cells and it can arise in any site of the body. The most common sites for primary lesions are liver and lung, but reports of primary lesions in bone, skin, spleen, pleura, and lymph nodes have also been reported.1 Under the classification of sarcomas, the World Health Organization defined EHE as an independent disease from other vascular tumors. EHE is such a rare disease, with an incidence rate of 1 in 1 million, that literature describing the entity is limited to case reports and small sample retrospective case series.1

Clinical Features: Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma affects women more than men at a 4:1 ratio and the median age of occurrence is 36 years old.1,2 These tumors are heterogeneous, with nearly a third of them presenting clinically as pulmonary EHE.2 Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma can be found in any site of the body and may or may not have symptoms specific to that body site. A cohort study of 33 patients diagnosed with EHE in various body sites showed 54.5% were asymptomatic and they had tumors with sizes ranging from 0.6-10.7 cm. EHE is typically discovered incidentally on physical examination or on imaging as a space-occupying lesion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful for diagnosing and analyzing the resectability of soft tissue tumors as they tend to present as isolated lesions. EHE presents as space-occupying lesions with low to middle signal intensity on MRI and on CT as low- or mixed-density tumors, which are considered nonspecific characteristics. 1

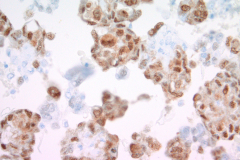

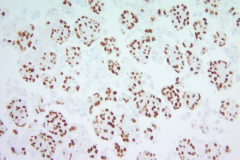

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) stains can also be an important tool in proper diagnosis of EHE. Stains such as CD31, CD34, and ERG have been described to stain EHE.2,3 CD31 is a platelet endothelial cell marker expressed frequently in vascular endothelial cells. CD34 stains for 90% of vascular tumors because it is a highly glycosylated transmembrane glycoprotein associated with the origin of vascular tumors. Positive staining for both CD31 and CD34 is considered diagnostic of this tumor.1 In this case, we have CAMTA1, a tumor suppressor transcription factor, staining positively for EHE shown in Image 1.

Treatment and Prognosis: For patients with a localized lesion, surgery is the primary treatment for epithelioid hemangioendothelioma tumors because they can be resected. Radiotherapy is used specifically for EHE lesions of the bone, and chemotherapy is administered to patients with advanced tumor lesions or deep tissue lesions. Because of the rarity of this tumor, standard treatment has not been established. EHE is insensitive to both radiotherapy and chemotherapy, stirring controversy on the best methods for treatment. Targeted therapies such as pazopanib, sorafenib, and bevacizumab have been reported as being successfully utilized. In some cases, tumors of EHE have spontaneously regressed.1

Prognosis of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma is unclear, but it can vary on the site of the primary tumor and its resectability, metastasis at initial diagnosis, and the stage of disease. Tumors that can be completely resected surgically give patients a cumulative survival rate of 96.2% for 1 year, 87% for three years, and 75.3% for five years according to a small cohort study with 33 patients who had confirmed EHE diagnosis.1 Within this study, patients with metastasis or patients who only underwent biopsy for a non-resectable tumor had poorer prognoses. Another case series of 49 EHE cases described high-risk patients as those with >3 mitotic figures per 50 high-powered fields (HPF) having a 5-year disease-specific survival of 59%.2 It was also described that having constitutional symptoms such as weight loss and anemia or displaying pulmonary symptoms such as hemorrhagic pleural effusions and hemoptysis, pose as risk factors for poorer prognosis.2

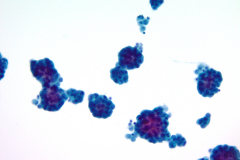

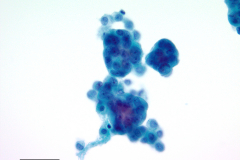

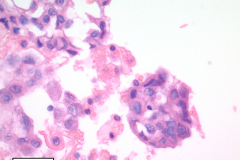

Cytology: Cytologic features suggestive of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma include spindle or polygonal epithelioid cells with moderate to abundant dense cytoplasm, well-defined cytoplasmic borders, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles and may present as single cells, small clusters or sheets. The large, eccentric nuclei are mildly pleomorphic with nuclear grooves, and nuclear cytoplasmic inclusions along with finely granular chromatin, irregular nuclear membranes, and nucleoli.4,5 Histologic features commonly seen in EHE include myxoid stroma, hyalinized stroma, and chondromyxoid stroma, as well as infrequent-to-frequent mitoses, erythrocytes, and a general absence of necrosis.3,4

This case reflects some of these features, including finely granular chromatin, enlarged, round nuclei, prominent nucleoli, dense and abundant cytoplasm, and formation of small groups. A fluid environment can also account for the cellular groupings seen in this case.

Nuclear grooves and erythrocytes can be seen in the cell block (Image 3).

Differential Diagnosis:

Adenocarcinoma is a top differential in this case because it was initially signed out as such based on cytological findings. Image 4 shows round cells grouped together with finely granular chromatin and nucleoli, and Image 5 has cells that form pseudo-rosettes and cells resembling signet-ring cells. Density of the cytoplasm should be taken into consideration when differentiating the two entities, however this criterion is not unique to epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Immunohistochemistry stains to confirm adenocarcinoma are TTF-1 for lung primary, and CK7, CK20 or CEA for gastric signet ring adenocarcinoma.10 ERG stains positive in prostate adenocarcinoma and endothelial cells which could be useful in this case of a female patient. 9

Hemangioma is a benign, relatively common soft-tissue tumor of blood vessels that affects young children most often. They are found in skin and subcutaneous tissue, particularly in the head, neck, and liver. Cytologically, they are round or spindle-shaped, appear singly or in sheets, and may have endothelial cells with moderate cytoplasm that may be pale and delicate to dense and homogenous. The nuclei are small, bland, and have nuclear grooves, which can mimic EHE. Mitoses without atypia may also be present.5 Unlike EHE, hemangiomas are often diagnosed on imaging by CT6 or MRI7 and in cytology, and these tumors lack prominent nucleoli.

Epithelioid Angiosarcomas are very rare soft-tissue sarcomas that normally appear in the skin, liver, and breast. Cytologically, they can take on a wide range of features. The endothelial cells of these tumors can be bland or pleomorphic. They can have a single-cell pattern in high-grade tumors with spindle-shaped to oval nuclei or can present in papillary groups with whorls or rosette-like groups important for diagnosis. Similar to EHE, the nuclei of low-grade tumors can have nuclear grooves, fine chromatin, and be slightly pleomorphic. High-grade tumors can also present with abundant cytoplasm, prominent nucleoli, and binucleation. Unlike EHE, epithelioid angiosarcomas can have hyperchromasia, large cell varieties, and can display erythrophagocytosis. DeMay describes this phenomenon as “an attempt at neovascularization.”5 IHCs that can help differentiate the two tumors include vimentin and cytokeratin markers AE1/AE3 for epithelioid angiosarcoma due to its epithelial origin.8 CAMTA1 can also be used to confirm epithelioid hemangioendothelioma over epithelioid angiosarcoma.2

Melanoma is a common differential because it can mimic several cancer types. Some common criteria it shares with EHE include a dispersed cell pattern, spindle-shaped cells, intranuclear inclusions, prominent nucleoli, abundant cytoplasm, eccentric nuclei, finely granular chromatin, and cytoplasmic vacuoles.5 One apparent difference between the two tumors is the presence of melanin to indicate a melanoma. Immunohistochemistry stains we can use in favor of melanoma are S100, Melan-A, and Ki67.11

References:

- Wu X, Li B, Zheng C, Hong T, He X. Clinical characteristics of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: a single-center retrospective study. European journal of medical research. 2019 Dec 1;24(1):16.

- Rosenberg A, Agulnik M. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: update on diagnosis and treatment. Current treatment options in oncology. 2018 Apr 1;19(4):19.

- Anderson T, Zhang L, Hameed M, Rusch V, Travis WD, Antonescu CR. Thoracic epithelioid malignant vascular tumors: a clinicopathologic study of 52 cases with emphasis on pathologic grading and molecular studies of WWTR1-CAMTA1 fusions. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2015 Jan;39(1):132.

- Murali R, Zarka MA, Ocal IT, Tazelaar HD. Cytologic features of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. American journal of clinical pathology. 2011 Nov 1;136(5):739-46.

- DeMay, RM. The Art and Science of Cytopathology. Volume II. Chicago, IL: ASCP; 1996.

- Nelson RC, Chezmar JL. Diagnostic approach to hepatic hemangiomas. Radiology. 1990 Jul;176(1):11-3.

- Yoon SS, Charny CK, Fong Y, Jarnagin WR, Schwartz LH, Blumgart LH, DeMatteo RP. Diagnosis, management, and outcomes of 115 patients with hepatic hemangioma. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2003 Sep 1;197(3):392-402.

- Gagner JP, Yim JH, Yang GC. Fine‐needle aspiration cytology of epithelioid angiosarcoma: A diagnostic dilemma. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2005;33(6):429-33.

- Miettinen M, Wang ZF, Paetau A, Tan SH, Dobi A, Srivastava S, Sesterhenn I. ERG transcription factor as an immunohistochemical marker for vascular endothelial tumors and prostatic carcinoma. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2011 Mar;35(3):432.

- Boutis AL, Andreadis C, Patakiouta F, Mouratidou D. Gastric signet-ring adenocarcinoma presenting with breast metastasis. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2006 May 14;12(18):2958.

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, Binder SW. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2008 May;35(5):433-44.