Case Presentation

Case Presentation – November 2021

Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma

Written by: Elisha Clapacs, Student, Cleveland Clinic School of Cytotechnology, Cleveland, Ohio

Patient Age: 70-year-old male

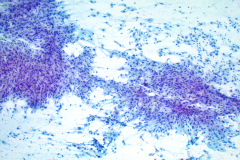

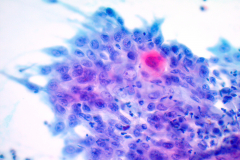

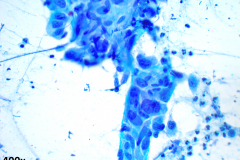

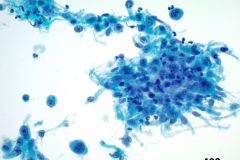

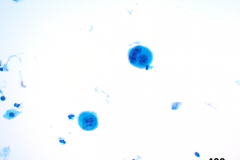

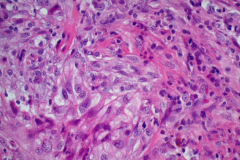

Specimen Type: Right lobe of thyroid, fine needle aspirate, ThinPrep® Non-Gyn, Pap-stained smears, H&E stained concurrent surgical biopsy

Patient History: Patient presented to neurology for headaches and was discovered to have a right anterior neck mass. A neck CT scan revealed a 4.2 x 5.5 x 5.4 cm heterogenous right lobe thyroid mass that was suspicious for thyroid carcinoma.

Cytologic Diagnosis: Positive for malignant cells; high grade carcinoma, most consistent with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. The tumor cells showed positive immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for AE1/3 and PAX-8, and focal positivity for p40. The specimen was negative for TTF-1 and p53.

Biopsy / Pathologic Diagnosis: Right lobe thyroid, biopsy. Undifferentiated (anaplastic) thyroid carcinoma. The anaplastic cells on cytology showed positivity for IHC stains AE1/3, CAM5.2, CK5/6, p63, TTF-1, PAX-8, p53, Ki-67, and BRAF V600E. The specimen was negative for thyroglobulin, synaptophysin, and chromogranin.

Case provided by: Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma

Etiology: There is no known obvious and singular predisposing factor for the development of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC). This type of cancer can develop de novo but has also been found to coexist with other types of thyroid carcinoma, suggesting that ATC may arise via dedifferentiation of other well differentiated thyroid carcinomas, specifically papillary thyroid carcinoma. However, there is a subset of patients under 50 who present with ATC without a well-differentiated carcinoma component, suggesting that healthy follicular cells can directly transform into an undifferentiated cell, and then progress into ATC.1 It has been posited that iodine deficiency and exposure to radiation may number among the causative agents for development of this type of carcinoma.2 All cases of ATC are considered to be stage IV, and all primary ATC tumors are classified as stage T4.1

Clinical Features: The most common clinical presentation of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma is the presence of a rapidly enlarging thyroid mass or gland. ATC occurs three times more frequently in women, and most often in patients who are older than 60, though the age range is wide (20-90 years of age).2 A longstanding history of nodular hyperplasia is also a common pattern of presentation.3 The main presenting symptoms or chief complaints for patients with ATC are related to the mechanical processes that accompany an enlarging neck mass, including stridor, dyspnea, dysphagia, and cervical pain.4 Though the extent of the disease is important, most patients end up expiring from local symptoms, mostly mechanical symptoms from tumor invasion.5

Treatment and Prognosis: The prognosis for ATC is extremely poor. ATC accounts for less than 5% of all thyroid cancers but is responsible for more than 50% of the deaths caused by thyroid cancer. The mortality rate for ATC is over 90%, with a survival rate of a mere six months after diagnosis.4 Combination therapy has proven to be the most effective method to combat ATC; a multidisciplinary approach involving a combination of therapies including radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery has been proven to increase survival rates.5 In many cases, surgery is not indicated, either due to distant progression of disease or involvement of local structures.6 In the current case presentation, the patient’s course of therapy included concurrent chemoradiation with paclitaxel and carboplatin.

One new treatment option involves targeted therapy based on the molecular profile of the tumor. The current patient’s tumor was positive for the BRAF V600E point mutation. This mutation has been identified in 25-45% of ATC cases, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors that target the altered BRAF gene (dabrafenib with trametinib) can be used in patients whose tumors harbor this mutation. This targeted treatment can decrease local tumor involvement and allows surgical resection, providing a better prognosis in some patients.6

Cytology: ATC specimens are usually highly cellular, and the cells present with an obviously malignant appearance. The malignant cells will be arranged in clusters and sheets, as well as found singly. The malignant cells themselves can have a varied appearance, and range from polygonal, epithelioid, giant cell-like, to spindled. The cells are often quite pleomorphic, vary wildly in shape and size, and frequently appear bizarre. The nuclei of the cells of ATC display criteria that are grossly malignant and include marked pleomorphism, irregular nuclear membranes,coarse, dark, and irregularly dispersed chromatin and prominent macronucleoli. Intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions are also possible findings but are not specific for this tumor type.

Mitotic figures are also common, including abnormal forms. The cytoplasm of ATC cells is often abundant and variable in appearance, and may be dense and squamoid, pale and vacuolated, or granular. The background is typically dirty and displays diathesis, necrosis, and acute inflammation. Colloid should be scant or absent. Another potential feature of ATC is the presence of osteoclast-like pleomorphic giant cells which may be multi- or mono-nucleated with mild nuclear irregularity.2,3

Differential Diagnosis:

Making the diagnosis of malignancy in a patient with ATC is typically easy, owing mostly to the highly malignant character of the neoplastic cells.3 However, a specific diagnosis of ATC can be challenging, particularly on fine needle aspiration biopsy. To confirm the diagnosis of thyroid carcinoma, immunohistochemical (IHC) stains thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and thyroglobulin are used. However, as ATC is a dedifferentiated or undifferentiated thyroid carcinoma, all ATC lose expression of thyroglobulin, and most ATC cells lose expression of TTF-1. In addition, ATC may only very weakly express other epithelial markers, or lose expression of them completely.1 Depending on the morphologic variant of ATC, there are different differential diagnoses to consider. The three most common variants of ATC are spindle cell, giant cell, and squamoid.5

With the spindle cell and giant cell variants of ATC, one of the main differentials is sarcoma. Primary thyroid sarcomas are very rare, and so the presentation of sarcomatoid cellular features should either be considered ATC or a metastatic sarcoma. Clinical data must be used to rule out a metastatic sarcoma, and in general, a sarcomatoid lesion arising in the thyroid without a history of other prior sarcoma should be considered ATC unless otherwise excluded. The features that qualify sarcoma as a differential diagnosis include spindled cells with elongated nuclei, coarse chromatin and fragile cytoplasm, as are present in both primary sarcomas and some cases of ATC. Some authors have reported that the main differentiating feature that separates ATC and sarcoma is the lack of frank cellular pleomorphism in sarcoma.1,4,7

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) can also be mistaken for ATC, as it can appear spindled and epithelioid. However, MTC specimens usually contain amyloid and the chromatin from MTC cells should be finely stippled (neuroendocrine type features). MTC also lacks the degree of nuclear pleomorphism ATC presents, and typically lacks necrosis or osteoclast-like giant cells, which are all common features of ATC. IHC stains such as chromogranin, synaptophysin and calcitonin may be used in this differential diagnosis, as MTC will be positive and ATC is negative for these stains.5,7

Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common differential diagnosis for the squamoid variant of ATC. The most likely site of SCC metastasis is from the lung. This subtype is characterized by both spindle elements and the presence of keratinization.4,7 The common features for both of these malignancies include enlarged nuclei, irregular nuclear membranes, keratinization, pulled out cytoplasm, and abnormally dispersed chromatin.2,7 PAX-8 is the best IHC stain as it would prove that the origin of the tumor is thyroid in nature, as PAX-8 is negative in SCC. The clinical presentation should also be considered to determine between ATC and SCC—lung SCC will have clinical evidence of a mass, while ATC presents as a rapidly enlarging thyroid mass.2-4

Reidel thyroiditis can present with a similar clinical picture as ATC; a rapidly enlarging thyroid mass entrapping local critical structures. However, fine needle aspirates of Reidel thyroiditis have scant cellularity, in opposition to ATC, and are characterized by reactive and plump spindled myofibroblasts.8,9 The features that distinguish benign Reidel thyroiditis from ATC include an absence of necrosis, mitotic activity, hyperchromasia and pleomorphism as these features are commonly found in ATC.1,4

References:

- Molinaro E, Romei C, Biagini A, et al. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: from clinicopathology to genetics and advanced therapies. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2017;13(11):644-660. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2017.76.

- Mody DR, Thrall MJ, Krishnamurthy S. Diagnostic Pathology: Cytopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018.

- DeMay, RM. The Art & Science of Cytopathology. 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: American Society of Clinical Pathology; 2012.

- Ragazzi M, Ciarrocchi A, Sancisi V, Gandolfi G, Bisagni A, Piana S. Update on Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma: Morphological, Molecular, and Genetic Features of the Most Aggressive Thyroid Cancer. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2014;2014:1-13. doi:10.1155/2014/790834.

- Are C, Shaha AR. Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma: Biology, Pathogenesis, Prognostic Factors, and Treatment Approaches. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2006;13(4):453-464. doi:10.1245/aso.2006.05.042.

- Wang JR, Zafereo ME, Dadu R, et al. Complete Surgical Resection Following Neoadjuvant Dabrafenib Plus Trametinib in BRAFV600E-Mutated Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma. Thyroid. 2019;29(8):1036-1043. doi:10.1089/thy.2019.0133.

- Ali SZ, Cibas ES. The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology: Definitions, Criteria, and Explanatory Notes. Cham: Springer; 2018.

- DeMay RM. The Book of Cells. United States: American Society for Clinical Pathology; 2016.

- Cibas ES, Ducatman BS. Cytology: Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014.