Case Presentation

Case Presentation – May 2021

Malignant Melanoma in a Pleural Fluid

Written by: Justin Arthur (student), Cleveland Clinic School of Cytotechnology, Cleveland, Ohio

Patient Age: 63-year-old male

Specimen Type: Right Pleural Fluid, ThinPrep® Non-Gyn cytology

Patient History: History of malignant melanoma on upper left shoulder in 2017.

Cytologic Diagnosis: Positive for malignant cells. Malignant Melanoma. The malignant cells are negative for AE1/3 and weakly positive for SOX10, supporting the diagnosis.

Case provided by: Cleveland Clinic Medina Hospital

Malignant Melanoma in a pleural fluid

Etiology: Malignant melanoma (MM) is a neoplasm of melanocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis, which are responsible for pigmentation in the skin1. The exact etiology of melanoma is unknown, but studies have identified a number of characteristics present in populations at high risk for developing melanoma. These include duration of exposure to UV-A and UV-B radiation, history of blistering sunburn, fair skin complexion and prior personal and family history2.

Clinical Features: Melanoma usually presents as a cutaneous lesion but metastasis to effusions can occur. During a clinical examination, the “ABCDE” system is routinely used for skin lesions that are suspicious. This system includes: Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation, Diameter larger than 6mm, and Evolution or timing of the lesion’s growth3. Common metastatic sites to see MM are in the lymph nodes, lungs, liver, and body cavity effusions4. The clinical presentation of a malignant pleural effusion includes shortness of breath, dry cough, and chest pain.

This patient had a prior history of cutaneous melanoma on his upper back 3 years prior and presented with dyspnea due to a right pleural effusion, right pleural masses, and bilateral pulmonary emboli.

Treatment and Prognosis: Surgical resection is the primary treatment for all stages of melanoma. Adjuvant therapy is recommended for patients with stages II, III, and IV, but the use of chemotherapy drugs is of little value to patients with stage IV melanoma. Patients with stage IV melanoma have a poor prognosis, with a survival rate of 6-9 months after diagnosis1. Patients with stage IV disease can be further subdivided into those with only cutaneous metastases (IVa), lung metastases (IVb), or other visceral metastases (IVc)5. These subcategories are useful for clinical trial stratification, but the overall prognosis of stage IV melanoma remains poor5. It is for this reason that the Melanoma Staging Committee recommends no stage groupings for stage IV5.

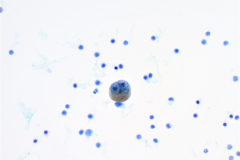

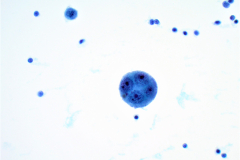

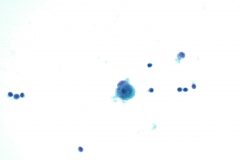

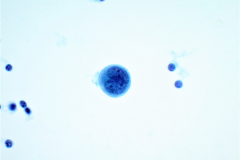

Cytology: MM is known as the “great mimicker”, as it can display a variety of morphologies, particularly in a setting of metastasis. Melanoma is classically seen as dispersed single cells and loose clusters with eccentric nuclei (plasmacytoid) that are often binucleated4. The nuclei can have prominent nucleoli, which are often large (macronucleoli). The cells may be epitheloid, spindled, or wildly pleomorphic. Melanin pigment may be present in the cytoplasm, but unfortunately this is not common4. In effusions MM cells closely resemble benign mesothelial cells. They are often isolated round cells with prominent nucleoli4. The nuclei are enlarged and often binucleated with increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios. Intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions can be seen, which can also aid in the diagnosis. Immunohistochemistry is helpful for these cases. Melanoma is positive for SOX10, S-100, HMB45, and Melan A, and is negative for keratin protein stains4. Mesothelial cells are positive for cytokeratin stains and negative for the melanoma markers mentioned above.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on this case with the atypical cells weakly positive for SOX10 and negative for AE1/3, supporting the diagnosis of MM.

Differentials of Melanoma in Fluids:

The cytomorphologic features in this case showed single dispersed cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios. Multiple cells were binucleated with prominent nucleoli and irregular coarse chromatin. A few cells contained melanin pigment in the cytoplasm which stain as finely granular brown particles on the PAP stain. Histiocytes with hemosiderin can closely mimic this brown pigment in the cytoplasm of malignant cells. With this being said, a diagnosis cannot be made off pigmented cells alone.

Adenocarcinoma:

Adenocarcinoma in fluids presents as 3D groupings/clusters with smooth community borders. It may present as single cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios. The nuclei are often enlarged and irregular, with hyperchromatic coarse chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Cytoplasmic vacuolization and signet ring cells can also be seen in metastatic adenocarcinoma presenting in fluids4, most classically in gastric or breast adenocarcinomas. In general, tumor cells will stain positive for BerEP4 and are negative for calretinin. Additional immunohistochemical stains may be positive depending on the site of origin.

Benign/Reactive Mesothelial cells:

Cells are present in flat sheets, small clusters or singly dispersed. They often have “windows” between them which suggests that they are mesothelial in origin. The nuclei are centrally located; reactive mesothelial cells often are binucleated with small nucleoli. The cytoplasm is abundant with a “lacy skirt” on the periphery, which is another morphologic indication of mesothelial origin4.

Mesothelioma:

Malignant mesothelial cells often have either a morular pattern (large clusters of cells with scalloped edges) or a dyshesive single cell pattern4. They may have normal or high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios and may have “windows” between cells. Abundant dense cytoplasm can be present with round or atypical nuclei. They are often binucleated with prominent nucleoli. The nuclear membranes can be smooth to irregular with the chromatin ranging from finely granular to coarse. Clinical history and biopsy are necessary to confirm a mesothelioma diagnosis. Using immunohistochemical stains to differentiate benign and malignant mesothelial cells is unreliable. Mesothelial markers such as WT1, D2-40 and calretinin can be helpful to differentiate mesothelioma from adenocarcinoma4.

References:

- Fisher RA, Larkin J. Malignant melanoma (metastatic). BMJ Clin Evid. 2010 Dec 21;2010:1718. PMID: 21418691; PMCID: PMC3275328.

- Leonardi GC, Falzone L, Salemi R, Zanghì A, Spandidos DA, Mccubrey JA, Candido S, Libra M. Cutaneous melanoma: From pathogenesis to therapy (Review). Int J Oncol. 2018 Apr;52(4):1071-1080. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2018.4287. Epub 2018 Feb 27. PMID: 29532857; PMCID: PMC5843392.

- Ward WH, Lambreton F, Goel N, Yu JQ, Farma JM. Clinical Presentation and Staging of Melanoma. In: Ward WH, Farma JM, editors. Cutaneous Melanoma: Etiology and Therapy [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Codon Publications; 2017 Dec 21. Chapter 6. PMID: 29461773.

- Cibas ES, Ducatman BS. Cytology: Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates. 4th 2014. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014. 146, 369.

- Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, Thompson JF,Atkins MB, Byrd DR, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol 2009;27: 6199–6206.