Case Presentation

Case Presentation – June 2022

Epithelioid Sarcoma

Written by: Summer Bledsoe, Student, Cleveland Clinic School of Cytotechnology, Cleveland, Ohio

Patient Age: 26 years old, Female

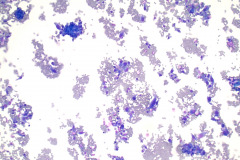

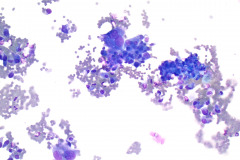

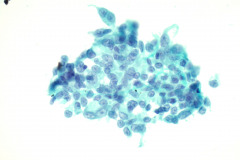

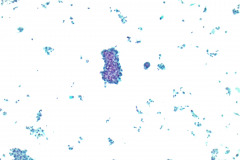

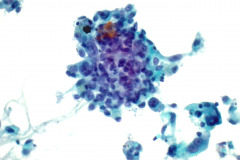

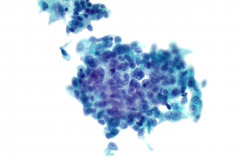

Specimen Type: FNA of Lung, Right Upper Lobe Nodule, Traditional smears with Diff-Quik and pap stain, ThinPrep® Non-Gyn

Patient History: History of epithelioid sarcoma involving the plantar fascia of the right foot and transmetatarsal amputation.

Cytologic Diagnosis: Positive for malignant cells, consistent with epithelioid sarcoma.

Biopsy / Pathologic Diagnosis: Immunohistochemistry stains are positive for AE1/AE3, EMA, ERG, and negative for CD34. Loss of INI1 nuclear expression. These results are consistent with epithelioid sarcoma. Surgical biopsy performed 8 months later diagnosed multifocal metastatic epithelioid sarcoma of the right lung upper, middle, and lower lobes.

Case provided by: Cleveland Clinic Main Campus

Epithelioid Sarcoma

Etiology:

Epithelioid sarcoma (ES) is an aggressive malignant soft-tissue tumor that is generally slow-growing and typically presents with nodular aggregates of epithelioid cells.1,2 ES is incredibly rare, constituting less than 1% of all diagnosed sarcomas.3 While the etiology of ES remains unknown, there is a possible association between ES and scar tissue due to cases involving previous trauma and tumor development.3 The most common genetic alteration in ES is the loss of integrase interactor 1 (INI1) function, which occurs in 90% of cases.2 INI1 is coded by the SMARCB-1 gene located at chromosome 22q.2

Clinical Features:

ES tumors predominantly occur in males and usually develop in young to middle aged adults, although they can also be seen in children and adolescents.2 Grossly, these tumors present as small, firm, or ulcerated nodules that can exist singly or in clusters.4

There are two subtypes of ES that present with differing features. The classical (also termed as distal) subtype primarily occurs in the extremities, most commonly the hands and wrists, and are generally superficial, involving the dermis, subcutis, tendons, or aponeuroses.5 Classical type ES is known to be slow growing and frequently causes pain and ulcerations.5 In contrast, the more aggressive proximal subtype of ES tends to be found in the deep soft tissue of the pelvis and peritoneum,5 occurs less commonly, and affects an older population.6 However, these subtypes are similar in that they can both occur anywhere in the body2 and tend to locally recur and regionally metastasize.1 The most common primary sites of metastasis involve the lung and pleura.2

Treatment and Prognosis: ES has a poor prognosis with an overall 5-year survival rate of 60% and an overall 10-year survival rate of 49%.4 This prognosis is likely due to the high rates of recurrence and metastasis, which have been reported as 63% and 42%, respectively.4 Factors that contribute to a poor prognosis include large or deep tumors, older age, history of local recurrence and presence of metastases.3 Unlike other soft tissue sarcomas, ES frequently metastasizes to regional lymph nodes and distant sites, specifically the lung.3 The proximal subtype has a poorer prognosis than the classical subtype because it tends to metastasize sooner.3

Localized ES tumors are usually treated with radical excision with microscopically radical margins and perioperative radiotherapy.2 In some cases of broad infiltration without the possibility of functional reconstruction, amputation may be necessary.2 A sentinel node biopsy may also be performed if lymph node metastasis is suspected.2 If lymph node metastasis has occurred, a therapeutic lymph node dissection will be performed.2 ES is generally radioresistant, however, radiotherapy (RT) is routinely used as an adjuvant to surgery.2 Unfortunately, neither adjuvant RT or chemotherapy have shown promising results for ES and there is currently no data on the effects of RT in recurrent or metastatic ES.2

Current adjuvant therapy options include preoperative RT, postoperative RT, systemic anthracycline-based chemotherapy, and postoperative chemotherapy.7 Patients who are suffering from distant metastasis can receive palliative treatment with various types of chemotherapy or RT with or without surgery.7 The FDA has recently approved tazemetostat, an EZH2 methyltransferase, for patients 16 and older who have metastasized or locally advanced ES and are not eligible for radical resection.2

Cytology: In fine needle aspirations of ES tumors, the specimens are usually moderately to highly cellular and the cytologic atypia can vary.6 ES tumors display a primarily single cell pattern with small, loosely cohesive clusters of cells mixed with a central fibrillary matrix.5 The cells can appear as polygonal, round, or spindle shaped with well-defined borders.5 It is common for the cells to be binucleated or multinucleated.5 The nuclei can be mild to moderately pleomorphic, and are large, round, and eccentrically placed.5 Clumped or vesicular chromatin and one or multiple small nucleoli can be observed.5 The cytoplasm of these cells can range from moderate to abundant and will be dense with small vacuoles.5 Necroinflammatory debris will often be present in the background of smears.5 In Romanowsky stains, a fibrillar metachromatic staining matrix can rarely be observed.6

Some cytologic differences exist between the two subtypes of ES tumors. The classical subtype usually presents with monomorphic, bland appearing epithelial cells with mild nuclear atypia.2 In contrast, the proximal subtype is more likely to display larger, more atypical cells along with necrosis and mitoses.5 The proximal subtype may present with a rhabdoid appearance, in which sheets of large, rounded cells display eccentric, vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusion bodies.1 Overall, the cytologic differences between the subtypes are minimal and they can both present in similar cytomorphologic patterns.6

In effusion specimens, ES tumors can present with 3D morular aggregates of cells with coarsely granular chromatin.6 Patterns of single cells with hypochromatic nuclei and prominent nucleoli can also be observed with a background of mesothelial cells.6 In early lesions, spindle cells can be commonly seen, but metastatic tumors usually present with atypical polygonal epithelioid cells.2

Differential Diagnosis: Due to the epithelioid morphology of ES, the possible differential diagnoses of ES are incredibly broad.6 The most beneficial ancillary test to use in the diagnosis of ES tumors is immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining, specifically for the loss of SMARCB-1 or INI1 expression.6 Unfortunately, SMARCB-1 expression can be lost in other uncommon neoplasms, so an extensive IHC panel is usually completed before these tumors are finally diagnosed.6 ES tumors also stain positively for pan-cytokeratin, which can increase the difficulty in distinguishing these tumors from carcinomas.6 Luckily, the morphological single cell pattern of ES would be unusual to find in most carcinomas.6

Malignant Rhabdoid Tumor (MRT) is a concerning differential because morphologically, it presents with a predominance of rhabdoid appearing cells that can be mistaken for the proximal subtype of ES.1 Additionally, MRT usually stains positive for cytokeratins, however, the expression will present in a dot-like pattern and the inclusion bodies typically only express CK8 and CK18 while ES will express many other cytokeratins.1 Also, while ES tends to express CD34, MRT usually does not.1 MRT mainly occurs in children younger than 3 years old, so the clinical information may also help to distinguish these entities.1

Epithelioid Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor (MPNST) is a major differential for ES because INI1 expression is lost in about 50% of cases.1 This tumor can occur in both superficial and deep soft tissues of the extremities.1 Epithelioid MPNST displays vague nodules of clusters or strands of large, rounded cells with prominent nucleoli that can appear similar to ES.1 However, it is often seen with foci of spindle cells intertwined with epithelioid cells.1 Fortunately, it commonly shows a diffuse and strong expression of S100 protein, which is usually absent in ES.1

Epithelioid Angiosarcomas can also be incredibly difficult to distinguish cytologically from ES.1 The majority of these tumors strongly express many of the same IHC markers as ES, including pan-cytokeratins, CD34, and ERG, which is expressed in about 40% of ES tumors.1 Additionally, most of these tumors express nuclear INI1, but it is possible for INI1 expression to be absent in some.1 However, small areas of vasoformation and foci of hemorrhage are commonly present in these tumors that should not be seen in ES.1 These tumors also express endothelial makers such as CD31, which should not be expressed in ES.1

Amelanotic malignant melanoma poses another diagnostic challenge when determining the presence of ES because these tumors can have remarkable morphological similarities.6 To distinguish these entities, an extensive IHC panel will need to include markers for melanoma such as S100, SOX10, HMB45, and melanA, which will be absent in ES.6

ES tumors may also morphologically resemble benign entities such as necrotizing granulomas, giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath, rheumatoid nodules, or fibrous histiocytomas.1 Necrotizing granulomas will have epithelioid histiocytes that display elongated and curved or indented nuclei that are not likely to be seen with ES in cytology.6 Additionally, these benign entities lack cytokeratin expression and most will not express EMA, both of which are usually diffusely expressed by ES.1 More cytological differentials of ES include epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma, mesothelioma, perivascular epithelioid cell tumor, or other various sarcomas that display epithelioid morphology.6

References:

- Thway K, Jones RL, Noujaim J, Fisher C. Epithelioid sarcoma: diagnostic features and genetics. Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 2016;23(1):41-9. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000102.

- Czarnecka AM, Sobczuk P, Kostrzanowski M, et al. Epithelioid sarcoma – from genetics to clinical practice. Cancers. 2020;12(8):2112. doi:10.3390/cancers12082112.

- Alves A, Constantinidou A, Thway K, Fisher C, Huang P, Jones RL. The evolving management of epithelioid sarcoma. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2021;30(6):e13489. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13489.

- Elsamna ST, Amer K, Elkattawy O, Beebe KS. Epithelioid sarcoma: half a century later. Acta Oncologica. 2020;59(1):48-54. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2019.1659514.

- Cibas ES, Ducatman BS, Jo VY, Qian X. Soft Tissue. In: Cytology: Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates. Fifth ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:581-584.

- Wakely PE. Cytopathology of classic type epithelioid sarcoma: a series of 20 cases and review of the literature. Journal of the American Society of Cytopathology. 2020;9(3):126-136. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2019.11.001.

- Asano N, Yoshida A, Ogura, K, et al. Prognostic value of relevant clinicopathologic variables in epithelioid sarcoma: a multi-institutional retrospective study of 44 patients. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2015;22(8):2624-32. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-4294-1.