Case Presentation

Case Presentation – July 2023

Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma

Written by: Jessica Coyne, student, Cleveland Clinic School of Cytotechnology, Cleveland, Ohio

Patient Age: 73-year-old male

Specimen Type: Main carina mass, fine needle aspirate, Diff Quik and Papanicolaou stained smears, ThinPrep® Non-Gyn cytology, and H&E stained cell block.

Patient History: The patient is a male non-smoker who presented to Pulmonology with a 3-4 month history of wheezing, cough, increasing discomfort on exertion, shortness of breath, and fatigue. A CT scan revealed a right hilar/mediastinal mass, measuring approximately 8.4 x 3.5 x 8.1 cm.

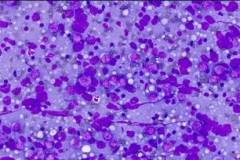

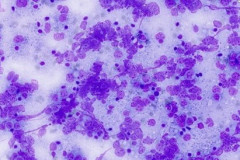

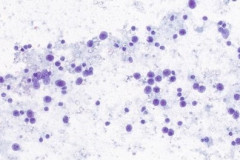

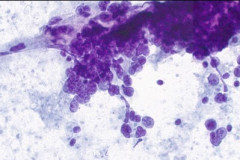

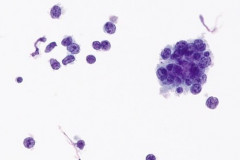

Cytologic Diagnosis: Positive for malignant cells. B-cell lymphoma. The main carina mass aspirate is cellular and contains a population of dyshesive medium to large-sized malignant cells with irregular nuclear outlines, small prominent nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm. The findings are consistent with B-cell lymphoma.

Biopsy / Pathologic Diagnosis: Mature aggressive B-cell lymphoma. The morphologic findings are consistent with involvement by a mature, aggressive B-cell lymphoma. The lymphoid cells are predominantly large in size with vesicular chromatin, variably prominent nucleoli and increased eosinophilic cytoplasm. The findings are compatible with a germinal center phenotype by Hans criteria based on expression of BCL6.

Case provided by: Cleveland Clinic

Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma

Etiology:

The predisposing factors for developing Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) include genetic features, clinical characteristics, occupational exposure, and viral aspects1. DLBCL can often arise from a pre-existing low-grade B-cell lymphoma and is not considered a heritable disease.1 Increased risk factors can include genetic susceptibility, increased BMI, Epstein-Barr virus, agricultural pesticides, and ionizing radiation.1 The majority of DLBCLs arise from normal antigen-exposed B cells that are at different stages of differentiation.2 These cells undergo clonal expansion in germinal centers which are susceptible to genetic mutations and chromosomal translocation errors, specifically in the Immunoglobulin gene remodeling process.2 Specific translocation errors include MYC, BCL2, and/or BCL6 rearrangement. The combination of these translocations can classify a lymphoma as a double-hit, having two translocation errors, or triple-hit having all three. The case described was not classified as a double or triple-hit lymphoma due to the expression of only BCL6.

DLBCL is divided into categories, high grade and not otherwise specified (NOS), with the most common being DLBCL (NOS). DLBCL-NOS is further categorized based on cell of origin (COO) and these subtypes include: germinal center B-cell like (GCB)-DLBCL, and activated B-cell like (ABC)-DLBCL.2 The GCB-DLBCL originate from light zone B-cells and express BCL6 and CD10, compared to the ABC subtype which expresses the MYC translocation.1, 2 This case is a GCB-DLBCL and expresses BCL6 phenotype.

Clinical Features:

The most common clinical presentation for Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma is progressive lymphadenopathy.1 Other clinical presentations include primary extranodal disease, which manifests as rapidly growing tumors in lymph nodes, liver, spleen, bone marrow, and other solid organs.1, 2 Primary extranodal disease most commonly affects elderly patients who are 65-70 years old with no sexual predilection.1

In our case, the patient presented with shortness of breath, cough, fatigue, and pain upon exertion. This initial clinical presentation prompted the patient to be consulted to pulmonology where a CT scan revealed a large main carina mass. Clinically, this patient has primary extranodal disease and falls within the typical age range. The patient was also found to have a mass in the right kidney as well as a hypodensity in the spleen.

Treatment and Prognosis:

The treatment and prognosis for DLBCL varies greatly from patient to patient and relies on stage and subtype. The 5-year prognosis for DLBCL is favorable (approximately 60-80%) since the introduction of R-CHOP immunochemotherpy.3 In general, patients are treated with various cycles of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), regardless of molecular subtype and immunohistochemical profile.1 Previously, 8 cycles of CHOP alone was the normal chemotherapeutic regimen for DLBCL, until the addition of an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, rituximab, led to a significant increase in overall survival making R-CHOP the preferred method.1

The different subtypes of DLBCL respond differently to the R-CHOP regimen. Patients with GCB-DLBCL, as described in this case, usually respond significantly better and have a more favorable 5- year survival rate compared to the ABC subtype of DLBCL.2 Patients with the ABC-DLBCL subtype have a poor prognosis when treated with R-CHOP alone due to this subtype being more aggressive.2 After initial diagnosis, patients with DLBCL are typically placed on numerous R-CHOP cycles, depending on the extent of disease. The patient is monitored through routine lab tests, PET/CT, and optional bone marrow biopsy to determine the effectiveness of treatment and the possibility of metastasis.1 If patients have a complete response to treatment or have achieved remission, they will be continually monitored for relapse.

Cytology:

DLBCL specimens have certain cytomorphologic criteria that can help aid in achieving an accurate diagnosis. Upon microscopic evaluation, DLBCL will display a predominantly large, uniform population of malignant cells with a high proliferation rate. 2, 4 The nucleus is 2.5-5 times larger than a small lymphocyte and has irregular nuclear outlines with vesicular chromatin and distinct large nucleoli.4 Cells will have moderate to scant basophilic cytoplasm and the background may contain lymphoglandular bodies, variable numbers of tingible body macrophages, and an absence of dendritic lymphocytic aggregates.2,4 In this case, the cells presented as a population of dyshesive, medium to large-sized malignant cells with irregular nuclear outlines, small prominent nucleoli and scant cytoplasm. The criteria described here match that of common DLBCL.

Cytomorphology can aid in the diagnosis of DLBCL, but it is not used alone, given that other tumors with similar morphology enter the differential diagnosis. Cytomorphology is paired with ancillary testing and correlated with clinical presentation. Immunohistochemistry (IHC), flow cytometry, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), and molecular testing are also used in combination with morphology. The most common ancillary test used to confirm the presence of lymphoma is flow cytometry. Flow characterizes mixed populations of cells from blood, bone marrow, and solid tissues.5 For smaller cell lymphomas, flow is a great way to detect abnormal populations of lymphoid cells; however, larger cell lymphomas may not survive the processing involved in flow cytometry because they are composed of fragile cells, or are considered to be outside the lymphoid gate range and are not detected.4 Therefore, a high grade lymphoma could come back with a negative flow result, such as in the case described here.4

Besides flow cytometry, IHC can be useful in the diagnosis of DLCBL. The lymphoid B-cells typically stain positively for CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, PAX5.1 In this case the cells were positive for CD20, and were negative for AE1/AE3, CAM 5.2, CD3, synaptophysin, chromogranin, INSM1, and TTF-1. The stains that were negative in the malignant cells were used to rule out the possibility of a small cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and other carcinomas. Ki-67 is a proliferation marker and is used as a prognostic and predictive marker in various tumors of the human body.6 In terms of DLBCL, Ki-67 may aid in determining non-GCB-type DLBCL versus GCB-type, as non-GCB type lymphomas, such as the ABC-type, have a higher Ki-67 index, and are associated with poorer prognosis and a higher proliferation rate.6

Molecular testing for BCL6 is used in determining if the DLBCL is of germinal center B-cell origin (GCB) or non-germinal center origin (NGC). This classification is very important as it greatly affects the treatment and prognosis for the patient. The expression of BCL6, as seen in this case, favors a germinal center origin.7 BCL6, BCL2, MYC, IRF4, IGH, IGK, and IGL translocations are detected by using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).7 FISH is used to classify lymphomas as double-hit, containing MYC/BCL6 translocations, or triple-hit, containing all three translocations MYC/BCL2/BCL6.7 This result is very important as it greatly affects treatment and overall survival for the patient.

Differential Diagnosis:

Definitely diagnosing a DLBCL in a patient can be rather challenging. Relying on clinical presentation, morphology, and correlation with ancillary tests is the key to an accurate diagnosis. Cytomorphologically, the differentials of DLBCL include small cell carcinoma, myeloid sarcoma, and thoracic SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated tumor. Clinically, small cell carcinoma and the SMARCA4 tumors would be unlikely in this patient due to his limited smoking history. However, morphologically they fall under the differential diagnosis for DLBCL.

Small cell carcinoma is a neuroendocrine carcinoma that can closely mimic DCBCL, but morphological features can help distinguish these two entities. Small cell carcinoma contains cells that are loosely aggregated, have scant cytoplasm, display nuclear molding, have “salt and pepper” neuroendocrine-type chromatin, a background of necrosis and crush artifact, paranuclear blue bodies, and a small to indistinct nucleolus.4 Small cell carcinoma can be distinguished from lymphoma by its tendency to form clusters while lymphoma will display prominent irregularly shaped nucleoli.4 The cells of small cell carcinoma stain positively for keratins, as well as neuroendocrine markers such as synaptophysin and chromogranin.

Myeloid sarcoma, synonymous with granulocytic sarcoma and chloroma, are tumors of immature myeloblasts and are either primary or in combination with acute myeloid leukemia.4 These myeloid blasts are large single cells that are dyshesive, with folded irregular nuclear membranes, dispersed chromatin, and nucleoli, and can exhibit a background of lymphoglandular bodies.4 IHC stains are positive for CD13, and CD123.4 Clinically and morphologically this case is not a myeloid sarcoma due to its features of non-blastoid cells expressing B-cell lineage markers.

Thoracic SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated tumors are poorly differentiated aggressive thoracic malignancies characterized by loss of function of the tumor suppressor gene BRG1. They typically stain negatively for keratins and show loss of staining with the SMARCA4 antibody by IHC.4,8 These cells are dyshesive and monomorphic with irregular nuclear borders and inconspicuous nucleoli in a background of extensive necrosis.4,8 Clinically they usually present as a large mediastinal mass in male smokers.4,8 The case presented here is not a Thoracic SMARCA4-deficient tumor because the patient did not have a loss of BRG1 expression and was a never-smoker.

References:

- Sehn LH, Salles G. Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(9):842-858. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2027612

- Camicia R, Winkler HC, Hassa PO. Novel drug targets for personalized precision medicine in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a comprehensive review. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:207. Published 2015 Dec 11. doi:10.1186/s12943-015-0474-2

- Frood R, Burton C, Tsoumpas C, et al. Baseline PET/CT imaging parameters for prediction of treatment outcome in Hodgkin and diffuse large B cell lymphoma: a systematic review. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48(10):3198-3220. doi:10.1007/s00259-021-05233-2

- Cibas ES, Ducatman BS. Cytology: Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2021

- McKinnon KM. Flow Cytometry: An Overview. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2018;120:5.1.1-5.1.11. Published 2018 Feb 21. doi:10.1002/cpim.40

- Hashmi AA, Iftikhar SN, Nargus G, et al. Ki67 Proliferation Index in Germinal and Non-Germinal Subtypes of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Cureus. 2021;13(2):e13120. Published 2021 Feb 4. doi:10.7759/cureus.13120

- Frauenfeld L, Castrejon-de-Anta N, Ramis-Zaldivar JE, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas in adults with aberrant coexpression of CD10, BCL6, and MUM1 are enriched in IRF4 rearrangements. Blood Adv. 2022;6(7):2361-2372. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006034

- Roden AC. Thoracic SMARCA4-deficient undifferentiated tumor-a case of an aggressive neoplasm-case report. Mediastinum. 2021;5:39. Published 2021 Dec 25. doi:10.21037/med-20-15