Case Presentation

Case Presentation – July 2021

Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma (LCNEC) of the Cervix Presenting in a Cervical Pap Test

Written by: Sarah Kline, student, Cleveland Clinic School of Cytotechnology, Cleveland, Ohio

Patient Age: 29-year-old female

Specimen Type: Cervical ThinPrep® Pap test

Patient History: This patient presented with post coital bleeding for several months and was found to have a large polypoid cervical mass on pelvic examination. A Pap test and cervical biopsy were performed.

Cytologic Diagnosis: Satisfactory for interpretation. Epithelial cell abnormality. Positive for malignant cells. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Biopsy Diagnosis: Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (CIN2)

Case provided by: Cleveland Clinic

Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Cervix Presenting in a Cervical Pap Test

Etiology:

Approximately 13,800 cases of invasive cervical cancer were diagnosed in 2020 with 4,290 deaths. The majority of these cancers were squamous cell carcinomas. Cervical high grade neuroendocrine carcinomas account for less than 1.5% of cervical carcinomas and encompass small cell carcinoma and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) is a high-grade carcinoma with a poor prognosis. It is composed of large tumor cells with neuroendocrine differentiation.1-2 LCNEC has been found to be associated with smoking and may coexist with other carcinomas.3-7 LCNECs of the cervix have been most commonly associated with HPV 18 and occasionally HPV types 16, 31 and 33.8

Clinical Features:

LCNEC presents as a cervical mass or polyp. Similar to other cervical cancers, the patients may experience symptoms such as vaginal discharge, post-coital bleeding, pelvic pain, weight loss, abdominal bloating, or symptoms related to metastatic disease.9 Sometimes a cervical polyp found on examination is noted.10 Patients present over a wide range in age 21-75 years with a median age of 37.11 The most common locations of metastasis are the lung and liver.10,11

Treatment and Prognosis:

While the majority of patients present with stage 1 disease, median overall survival is poor (16.5 months).11 Patients with this tumor are likely to have early, distant metastases and a worse prognosis than other tumors of the cervix in spite of treatment modality.12,13 Survival rates for patients with LCNEC decrease from 16.5 months to 1.5 months depending on stage.11 Early staging along with radical hysterectomy and platinum-based combination chemotherapy has been shown to allow patients to be disease and symptom free up to 5 years later.10 Improved prognosis and survival have been correlated with an early stage diagnosis, chemotherapy, and surgery, especially a radical hysterectomy.11 Chemotherapy regimens including platinum or platinum and etoposide were associated with improved survival versus chemotherapy regimens without these drugs. However, it is still expected that around seventy percent of women will develop a recurrence.11,14

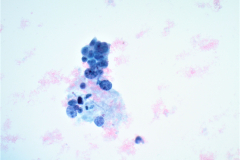

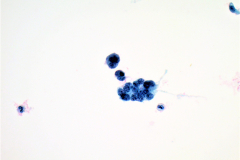

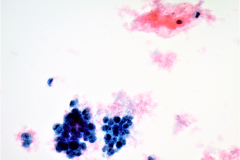

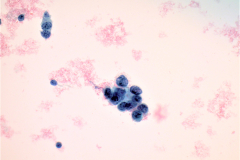

Cytology:

LCNECs share some of the same features of small cell carcinoma but in LCNEC the cells are larger, have abundant cytoplasm, are polygonal in shape, and show less nuclear molding then the cells of small cell carcinoma. The neoplastic cells are pleomorphic with vesicular nuclei and neuroendocrine type “salt and pepper” chromatin and irregular chromatin clumping. LCNEC cells display molding and cupping. The nuclei may appear more pyknotic and smudged due to degeneration. LCNECs have a very high mitotic rate, with 8-19 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields. Prominent nucleoli are also identified. Necrotic debris is seen, and tumor cells are present in 3D clusters as well as in single cell arrangement. Streaks of nuclear debris and apoptotic bodies are generally not found.

Differential Diagnosis:

Immunohistochemical stains are important in differentiating LCNEC from other neoplasms. LCNECs stain positively with neuroendocrine markers including CD56, chromogranin, synaptophysin, and INSM1.15 These tumors are also diffusely positive for p16 and cytokeratins. High risk HPV may be identified using chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH).

Endometrial cells16 – Endometrial cells are a common benign finding in cervical cytology of women under 45 years of age. They are typically shed during menses and during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle. The small columnar cells form tight, overlapping, 3D clusters and the nuclei around the edges of the clusters may be cup-shaped. The nuclei are dark and slightly smaller than the nuclei of a normal intermediate squamous cell. Nucleoli are inconspicuous, mitoses are absent, and karyorrhexis is often seen. The cytoplasm of endometrial cells is scant and occasionally vacuolated and cell borders are ill defined. In atypical endometrials, the cell groupings will be smaller, containing around 5-10 cells. These cells will have mild hyperchromasia and occasional small nucleoli. Differentiation between atypical endometrials and benign is based on increased nuclear size in the atypical cells. The background may be bloody or inflammatory.

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL)16 – Cells of HSIL occur singly, in sheets, or in syncytial aggregates so hyperchromatic crowded groups can be seen. The cytoplasm can appear immature, lacy, and delicate or densely metaplastic. Nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios are high. Nuclei of HSIL are hyperchromatic with fine or coarsely granular and evenly distributed chromatin. The cells display anisonucleosis and irregular nuclear membrane contours with prominent indentations. Nucleoli are generally absent but can occasionally be seen. HSIL can often be found in a background of low-grade intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) and inflammation.

Lymphoma – Lymphomas, such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), typically lack cohesion and present in a single cell pattern. These cells are large and often pleomorphic with irregular nuclei. Cytoplasm is variable and occasionally vacuolized. Chromatin is coarse and small nucleoli are identified.17 DLBCL stains positive for lymphoid markers such as CD19 and CD20 but cytokeratin stains will be negative.18

References:

- Siegel R, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7-30.

- Brambilla E,Travis WD, Colby TV, Corrin B, Shimosato Y. The new World Health Organization classification of lung tumours. Eur Respir J. 2001;18(6):1059-1068.

- 3. Travis W, Nicholson S, Hirsch FR, et al. Small cell carcinoma. In: Travis W, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, et al., eds. Pathology and Genetics. Tumors of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. World Health Organization. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004:31–4.

- Gilks CB, Young RH, Gersell DJ, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathologic study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:905–14.

- Cetiner H, Kir G, Akoz I, et al. Large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix associated with cervical-type invasive adenocarcinoma: a report of case and discussion of histogenesis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:438–42.

- Manivel C, Wick MR, Sibley RK. Neuroendocrine differentiation in Mullerian neoplasms. An immunohistochemical study of a “pure” endometrial small cell carcinoma and a mixed Mullerian tumor containing small cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1986;86:438–43.

- Stahl R, Demopoulos RI, Bigelow B. Carcinoid tumor with a squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1981;11:387–92.

- Kuroda N, Wada Y, Inoue K, et al. Smear cytology findings of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;41(7):636-639.

- Barakat RR, M.M., Randall ME. Principles and Practice of Gynecologic Oncology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Martinez-Benitez B, Luevano E. Small cell carcinomas and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas of the endometrium and cervix: polypoid tumors and those arising in polyps may have a favorable prognosis. Int J of Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27:333-339.

- Embry JR, Kelly MG, Post MD, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: Prognostic factors and survival advantage with platinum chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;120:444-448.

- Sato Y, Shimamoto T, Amada S, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathologic study of six cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2003;22:226–30.

- Dikmen Y, Kazandi M, Zekioglu O, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Obstet Gynecol. 2003;270:185–8.

- Albores-Saavedra J, Gersell D, Gilks CB, et al. Terminology of endocrine tumors of the uterine cervix: results of a workshop sponsored by the College of American Pathologists and the National Cancer Institute. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121(1):34-9.

- Gilks CB, Young RH, Gersell DJ, et al. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a clinicopathologic study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:905–14.

- Nayar R, Wilbur DC, eds. The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology. 3rd ed. Chicago, IL: Springer; 2015.

- Mohiuddin Y, Hong H, Juskevicius R. Cytological features of diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma can mimic metastatic carcinoma on fine needle aspiration cytology. Cytopathol. 2012;24(5):340-342.

- Pathology Outlines. Stains (IHC & special) & molecular markers. https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/stains.html. Accessed February 26, 2021.