Case Presentation

Case Presentation – October 2025

Paraduodenal (Groove) Pancreatitis

Written by: Joanna DeSalvo, student, Cleveland Clinic Cytology Program, Cleveland, Ohio

Patient Age: 52-year-old female

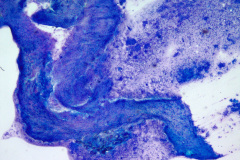

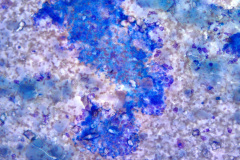

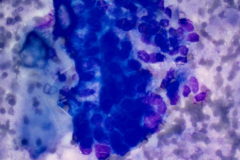

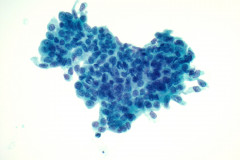

Specimen Type: Pancreatic head mass, fine needle aspirate: Modified Romanowsky-stained smears, Pap-stained ThinPrep® Non-Gyn slide, and Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E)-stained Cellient® cell block. Pancreatectomy, surgical resection specimen: H&E-stained tissue

Patient History: Patient presented with epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. History of recurrent pancreatitis, appendectomy, cholecystectomy. Multiple emergency department visits in the preceding year with a 1-cm lesion in the pancreatic head unchanged over the previous 3 months.

Cytologic Diagnosis: Pancreas, head, FNA: Rare atypical cells favor neoplastic. See comment.

“The rare atypical cells are predominantly seen on the needle rinse sample. The smears show mostly calcification/ crystalline debris, amorphous material, few ductal cells and gastrointestinal tract contaminant. Fibrous stroma are also present. While the rare atypical cells are favored to be neoplastic, correlation with the clinical/ radiologic findings is recommended.”

A repeat pancreatic head/uncinate FNA after a month was diagnosed as negative for malignancy, with “Acute and chronic inflammation, histiocytes and fragments of inflamed fibrous tissue.”

Pathologic Diagnosis: Pancreas, Whipple procedure: “Chronic and paraduodenal (“groove”) pancreatitis with cystic degeneration and acinar atrophy.”

Case provided by: Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

Paraduodenal (Groove) Pancreatitis

Etiology:

Paraduodenal (groove) pancreatitis (PGP) is a form of chronic pancreatitis commonly involving the groove-like space between the duodenum, the head of the pancreas, and the common bile duct.1,2 It occurs predominantly in middle-aged males with a history of alcohol abuse and/ or cigarette smoking, which are thought to increase the viscosity of pancreatic fluid secretions, leading to obstructions at the pancreaticoduodenal junction.1 Variations in pancreatic duct anatomy and the presence of pancreatic parenchyma in the wall of the duodenum are factors that may predispose individuals to PGP through increased sensitivity to alcohol-induced changes.1,3 Genetic variants in the expression and modulation of pancreatic enzymes have also been implicated in the development of various forms of pancreatitis.4

Clinical Features:

Symptoms commonly include severe upper abdominal pain, weight loss, diarrhea, and recurrent postprandial vomiting due to stenosis of the duodenum or occlusion of the minor papilla.1,2 Jaundice does not typically occur unless there is an occlusion of the bile duct and is seen later in the course of disease.3

Imaging by CT and MRI typically reveal a thickening of the duodenal wall, which can be caused by underlying Brunner gland hyperplasia, smooth muscle proliferation, fibroinflammatory processes, or the presence of nodular, often cystic, lesions.1,5

Treatment and Prognosis:

The symptoms of paraduodenal pancreatitis can be severe and can last for months or years.2 Complications can include gastrointestinal hemorrhage and malignant transformation of heterotopic pancreatic tissue.6 Effective treatments range from behavior modifications to surgical removal of the pancreas and duodenum.4,6

Conservative approaches include analgesic management of pain, cessation of alcohol and/or smoking, and fasting or dietary changes.6 EUS-mediated treatments can include drainage of cystic lesions, placement of stents for duct occlusions, or nerve blocks at the celiac plexus for relief of abdominal pain.2 Surgical intervention may be required to remove obstructions in the minor papilla, pancreatic duct, or common bile duct.2 Surgical resection of the pancreas and duodenum (pancreaticoduodenectomy or the Whipple procedure) is performed when malignancy cannot be excluded or when other measures have been inadequate in addressing symptoms. Up to 25% of such resections are identified as paraduodenal pancreatitis post-operatively.3 One advantage of surgical resection over EUS for diagnosis is avoiding the risk of tumor needle seeding in cases of malignancy.7

Cytology:

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) can be used in combination with radiological and clinical features to diagnose paraduodenal pancreatitis.2,5 Given the anatomic site, diverse histopathological presentations of this entity, and variations inherent to FNA sampling, the range of cytological features that can be seen on FNA is broad.2 Since fibrosis and stromal proliferation are a key feature of PGP, commonly reported findings on FNA are chronic inflammatory infiltrates, fibrotic tissue fragments, spindled stromal cells, and proteinaceous debris.8,9 Cellular elements frequently include smooth muscle, myofibroblasts, and Brunner gland cells.5,8,10 Eosinophils and plasma cells may be seen, although large numbers of plasma cells are more typical of autoimmune pancreatitis.2,11 Multinucleated giant cells may also be present and are thought to constitute a foreign body reaction to the abundant deposits of mucoprotein material associated with PGP pathology.1,5,12

The FNA specimen for this case featured low to moderate cellularity with a predominance of fibrotic stroma, chronic inflammation, proteinaceous debris, and ductal epithelium ranging from benign to atypical cells (loss of polarity, mild anisonucleosis, and conspicuous small nucleoli). A subsequent FNA was negative for malignancy with acute and chronic inflammation, histiocytes, and inflamed fibrous tissue. In retrospect, and on review of the pancreatectomy specimen, the initial diagnosis of cytologic atypia represents a reactive change given the presence of chronic inflammation and extensive fibrosis. Given that atypia could be a potential pitfall, familiarity with the cytologic findings of pancreatitis, such as seen in PGP (fibrotic tissue fragments, chronic inflammatory cells, and proteinaceous debris), will be helpful.

Differential Diagnosis:

The diagnosis of paraduodenal pancreatitis can be challenging, with other inflammatory entities, benign neoplasms, and malignancies among the differentials. Due to numerous overlapping cytological and radiological features, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), particularly well-differentiated PDAC, is a major differential in the diagnosis of PGP.9,11 Cytologically, both PGP and PDAC typically feature abnormal fibrotic stroma and abnormal ductal epithelium.9,13 PDAC criteria include four-fold or greater nuclear enlargement within a group, hyperchromatic nuclei, nuclear membrane irregularities, and a disordered or drunken honeycomb arrangement in glandular groups.9,14 In well-differentiated variants of PDAC, nuclear and architectural atypia may be more subtle, with bland nuclei and less pronounced anisonucleosis presenting a considerable challenge for differentiation from the reactive ductal changes in PGP.9 Sampling of hyperplastic Brunner glands in PGP can also suggest well-differentiated PDAC, specifically a foamy variant characterized by abundant microvesicular cytoplasm.10 To aid in this distinction, foamy gland PDAC may feature a thin chromophilic band at the apical cytoplasmic border, and Brunner gland origin can be identified by positive MUC6 immunostaining.10,15 Generally, in considering well-differentiated PDAC as a differential of PGP, anisonucleosis without nuclear membrane irregularities supports a benign diagnosis.14,15 The presence of both acinar and ductal components on a smear should also favor PGP.11 Mitoses and nucleoli can be present among PGP-induced epithelial changes and do not assure malignancy.9,13

Conversely, the presence of single malignant cells and necrosis favors PDAC over PGP.13,14 A granular background with abundant debris in PGP aspirates may suggest necrosis.5 In combination with multinucleated giant cells and markedly atypical single cells, the differential might include undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclastic giant cells (UDCOGC). 9,12 UDCOGC is a rare subtype of undifferentiated pancreatic carcinoma classified as a variant of PDAC. While most UDCOGC occur in the body or tail of the pancreas, they can also arise in the pancreatic head or hepatopancreatic ampulla.16 UDCOGC is characterized by the presence of non-neoplastic multinucleated “osteoclast-like” giant cells in combination with two populations of mononuclear epithelial tumor cells—large, pleomorphic tumor cells and smaller malignant cells that can be ovoid to spindle-shaped.9,12,16 To rule out UDCOGC, the presence of multinucleated giant cells in pancreas FNAs should prompt a search for this atypical epithelioid component.9,12 The multinucleated giant cells in chronic pancreatitis tend to contain relatively few nuclei (2-5) compared with those of UDCOGC.9

Spindled cells are commonly seen in paraduodenal pancreatitis aspirates, and tissue sampled from or near the pancreas might suggest a spindle cell neoplasm, especially when stromal cells are abundant or atypical.3,5 Mesenchymal neoplasms that can present as cystic lesions near the pancreas include Schwannomas and Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST).6 GIST arising from the duodenum typically have cystic changes and imaging features similar to paraduodenal pancreatitis.3,6 A dual stain for the immunohistochemical markers CD117 and DOG1 will positively identify 98% of GIST, and one or both markers can be used to support the diagnosis.17

References:

- Adsay NV, Zamboni G. Paraduodenal pancreatitis: a clinico-pathologically distinct entity unifying “cystic dystrophy of heterotopic pancreas,” “para-duodenal wall cyst,” and “groove pancreatitis.” Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology. 2004;21(4):247-254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semdp.2005.07.005

- Raman SP, Salaria SN, Hruban RH, Fishman EK. Groove Pancreatitis: Spectrum of Imaging Findings and Radiology-Pathology Correlation. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 2013;201(1):W29-W39. doi:https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.12.9956

- Neto C, Palmela C, Soares AS, Antunes ML, Fidalgo CA, Luísa Glória. Groove Pancreatitis: Clinical Cases and Review of the Literature. GE Portuguese Journal of Gastroenterology. 2022;30(6):437-443. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000526855

- Whitcomb DC. Genetic Risk Factors for Pancreatic Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(6):1292-1302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.069

- Chute DJ, Stelow EB. Fine-needle aspiration features of paraduodenal pancreatitis (groove pancreatitis): a report of three cases. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2012;40(12):1116-1121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.21722

- Pallisera-Lloveras A, Ramia-Ángel J, Vicens-Arbona C, Cifuentes-Rodenas A. Groove pancreatitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107(5):280-288. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/diges/v107n5/revision.pdf

- Kitano M, Kosuke Minaga, Keiichi Hatamaru, Ashida R. Clinical dilemma of endoscopic ultrasound‐guided fine needle aspiration for resectable pancreatic body and tail cancer. Digestive Endoscopy. 2021;34(2):307-316. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/den.14120

- Basturk O, Askan G. Benign Tumors and Tumorlike Lesions of the Pancreas. Surgical Pathology Clinics. 2016;9(4):619-641. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.path.2016.05.007

- Wang Q, Reid MD. Cytopathology of solid pancreatic neoplasms: An algorithmic approach to diagnosis. Cancer Cytopathology. 2022;130(7):491-510. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cncy.22597

- Ortiz Requena D, Rojas C, Garcia‐Buitrago M. Cytological diagnosis of Brunner’s gland adenoma (hyperplasia): A diagnostic challenge. Diagnostic Cytopathology. 2020;49(6). doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.24680

- Pitman MB, Deshpande V. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology of the pancreas: a morphological and multimodal approach to the diagnosis of solid and cystic mass lesions. Cytopathology. 2007;18(6):331-347. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2303.2007.00457.x

- Brosens, L.A.A, Leguit RJ, Vleggaar FP, Veldhuis WB, Leeuwen van, G. J. A. Offerhaus. EUS‐guided FNA cytology diagnosis of paraduodenal pancreatitis (groove pancreatitis) with numerous giant cells: conservative management allowed by cytological and radiological correlation. Cytopathology. 2014;26(2):122-125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cyt.12140

- Reid M. Cytology of the Pancreas: A Practical Review for Cytopathologists. Surgical pathology clinics. 2011;4(2):651-691. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.path.2011.03.006

- Lin F, Staerkel G. Cytologic criteria for well differentiated adenocarcinoma of the pancreas in fine-needle aspiration biopsy specimens. Cancer. 2002;99(1):44-50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11012

- Adsay V, Logani S, Sarkar F, Crissman J, Vaitkevicius V. Foamy Gland Pattern of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2000; 24 (4): 493-504. Accessed March 9, 2025. https://journals.lww.com/ajsp/abstract/2000/04000/foamy_gland_pattern_of_pancreatic_ductal.3.aspx

- Abid H, Gnanajothy R. Osteoclast Giant Cell Tumor of Pancreas: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus. 2019;11(5). doi:https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4710

- Wu CE, Tzen CY, Wang SY, Yeh CN. Clinical Diagnosis of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST): From the Molecular Genetic Point of View. Cancers. 2019;11(5):679. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11050679