Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology – Head, Neck and Lymph Nodes

HEAD, NECK AND LYMPH NODES

Stan A. Lightfoot, MD

Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) of the head and neck can be organized in many ways but preferentially divided into two groups: lumps and bumps and salivary gland lesions.

Lumps and Bumps

History and age are very important. In children the vast majority of these lesions are benign and inflammatory. In adults the majority of lesions are malignant, with the most common cause being metastatic squamous cell carcinoma. History is essential here. Most metastatic squamous cell carcinomas in the neck come from the oropharynx but can uncommonly come from the lung and even less often from a squamous cell carcinoma of the head or face. In the latter case, the diagnosis of the skin cancer has already been made and it is one that has invaded deeply into the dermis or is of longstanding duration.

Lung cancer does not usually metastasize to neck nodes, so that leaves the oropharynx as the site of the primary lesion. Again history is important as at least 80% of these will already have a prior diagnosis of oropharyngeal cancer thus prompting an FNA for staging purposes or assessment of recurrence. At our institution, 20% of the time the patient’s primary presentation is metastatic squamous cell carcinoma in a neck lymph node. If the squamous cell in the node is in intimate contact with mature lymphocytes, this is strongly suggestive of a nasopharyngeal primary. Otherwise morphologic features are of little help with regard to location of the primary. When this 20% is worked up, a certain number will have no symptoms or signs that help determine the primary lesion. In these cases blind biopsies of the nasopharynx, tonsil and vocal cords are performed. At our institution, if no tumor is found the patient receives irradiation of the entire head and neck region. This results in a 70% 5 year survival.

Lumps and bumps may also be metastatic malignant melanoma particulary in southern rural populations with high sun exposure. The neck is a favorite site for this lesion and it must be remembered because it can mimic lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease and carcinoma. We will revisit this when we talk about salivary gland lesions below.

If the FNA exhibits an atypical lymphoid proliferation the specimen should be taken for flow cytometry examination. Examination of the case is facilitated by preparing at least one Wright stained slide in addition to several Pap-stained ThinPrep slides in all lymphoid lesions. Several things assist with regard to lymphoid lesions and the FNA. Are the lymphocytes of monotonous or heterogeneous morphology? Are there notches and cuts into the nuclear membrane? Are nucleoli present? The utility of these features is discussed in the attached illustrations.

Lumps and bumps may also be due to benign cysts. In the neck the two most common benign cysts are a branchial cleft cyst or a thyroglossal duct cyst. Both contain many macrophages and a variety of other cells. Cysts may contain atypical squamous cells which may lead to a false positive diagnosis of metastatic disease. If the cyst is tense, and it frequently is, it may feel very firm to the touch. So be wary in the presence of macrophages that you are not dealing with a benign cyst even if there are occasional atypical squamous cells!

I have left the Salivary Gland FNA’s for the last discussion, because it is the most difficult topic, requiring experience. FNA’s of the salivary gland may be very easy, as in a Warthin tumor or difficult, as in an adenoid cystic carcinoma. However, to be proficient in this area requires abundant experience that cannot be acquired by reading a book. There are several key points regarding the cytology of these glands. The parotid is a favorite site for metastatic disease, notably squamous cell carcinoma. So if the FNA has only well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, it is almost always metastatic to the parotid. Similar to the neck, lung carcinomas rarely go to the parotid, so a small cell carcinoma in the parotid may indeed be a primary lesion. The lung must be ruled out, but in our experience small cell carcinoma in the parotid is usually primary. And malignant melanoma, true to its name as the great imitator, can complicate the diagnosis of parotid lesions. As an example, recent cases of presumed primary parotid carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma were in fact metastatic malignant melanomas.

I would like to thank Susan Townsend, CT(ASCP), and Vala Williams, Preparatory Technician, for their help with this project.

References

- Al-Khafaji BM, Afify AM: Salivary gland fine needle aspiration using the ThinPrep technique. Acta Cytol 2001; 45:567-74.

- Ford L, Rasgon BM, Hilsinger RL, Cruz RM, Axelsson K, Rumore GJ, Schmidtknecht TM, Puligandla B, Sawicki J, Pshea W: Comparison of ThinPrep versus conventional smear cytopreparatory techniques for fine-needle aspiration specimens of head and neck masses. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002; 126(5):554-61.

- Leon ME, Deschler D, Wu SS, Galindo LM: Fine needle aspiration diagnosis of lipoblastoma of the parotid region. Acta Cytol 2002; 46(2): 395-404.

- Chen VS M, Qizilbash A , and Young JE : Guides to Clinical Aspiration Biopsy, Head and Neck, 2nd edition. Igaku-shoin Ltd; Tokyo, 1996.

What role does the ThinPrep® technology play in the diagnosis of FNA’s from this area? The best way to answer that is to look at the examples:

Reminder: You may click on any slide image

for an enlarged view.

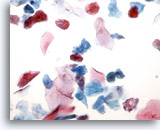

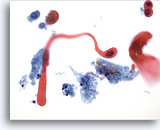

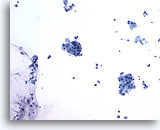

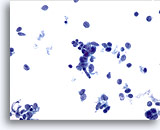

Figure 1

Neck FNA, benign cyst.

An admixture of cells including benign squamous cells and smaller inflammatory cells are present. Also abundant keratin is seen. 20x

Neck FNA, benign cyst.

An admixture of cells including benign squamous cells and smaller inflammatory cells are present. Also abundant keratin is seen.

20x

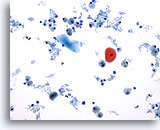

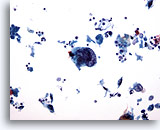

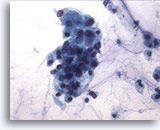

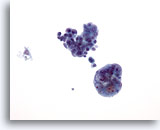

Figure 2

Neck FNA, benign cyst.

Benign squamous cells, inflammatory cells and keratin are seen in this aspirate. Note the benign metaplastic squamous cells . These are frequently found in the aspiration of cysts. 40x

Neck FNA, benign cyst.

Benign squamous cells, inflammatory cells and keratin are seen in this aspirate. Note the benign metaplastic squamous cells . These are frequently found in the aspiration of cysts.

40x

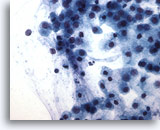

Neck FNA, branchial cleft cyst.

Mature squamous cells, keratin debris and anucleated squamous cells indicate a benign cystic process. 10x

Neck FNA, branchial cleft cyst.

Mature squamous cells, keratin debris and anucleated squamous cells indicate a benign cystic process.

10x

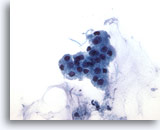

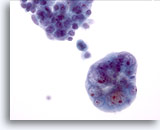

Figure 4

Neck FNA, branchial cleft cyst.

Also known as lymphoepithelial cysts, these usually occur along the lateral aspects of the neck. 40x

Neck FNA, branchial cleft cyst.

Also known as lymphoepithelial cysts, these usually occur along the lateral aspects of the neck.

40x

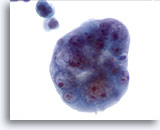

Figure 5

Neck FNA, thyroglossal duct cyst.

Cystic debris, histiocytes and benign squamous cells indicate a benign cystic process. 20x

Neck FNA, thyroglossal duct cyst.

Cystic debris, histiocytes and benign squamous cells indicate a benign cystic process.

20x

Figure 6

Neck FNA, thyroglossal duct cyst.

Located along the neck’s midline, these cysts are lined with columnar or squamous epithelium which may or may not be seen upon aspiration. 40x

Neck FNA, thyroglossal duct cyst.

Located along the neck’s midline, these cysts are lined with columnar or squamous epithelium which may or may not be seen upon aspiration.

40x

Figure 7

Neck FNA, thyroglossal duct cyst.

This cyst contained mature squamous epithelium. Some FNA’s may not be diagnostic. 40x

Neck FNA, thyroglossal duct cyst.

This cyst contained mature squamous epithelium. Some FNA’s may not be diagnostic.

40x

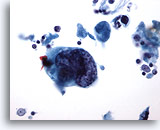

Figure 8

Neck FNA, suspicious for squamous carcinoma.

In the center of the photo is a squamous cell with a slightly enlarged, atypical nucleus. It is surrounded by inflammatory cells, keratin and necrotic material. 20x

Neck FNA, suspicious for squamous carcinoma.

In the center of the photo is a squamous cell with a slightly enlarged, atypical nucleus. It is surrounded by inflammatory cells, keratin and necrotic material.

20x

Figure 9

Neck FNA, suspicious for squamous carcinoma.

The atypical cell is more clearly seen. The nucleus is enlarged but has an absolutely smooth nuclear membrane and is perfectly oval. It is again surrounded by keratin, inflammatory cells and necrotic debris. 40x

Neck FNA, suspicious for squamous carcinoma.

The atypical cell is more clearly seen. The nucleus is enlarged but has an absolutely smooth nuclear membrane and is perfectly oval. It is again surrounded by keratin, inflammatory cells and necrotic debris.

40x

Figure 10

Neck FNA, suspicious for squamous carcinoma.

Cells with similar morphology can occur in a benign cyst. Thus, this finding alone does not support an unequivocal diagnosis of malignancy. 60x

Neck FNA, suspicious for squamous carcinoma.

Cells with similar morphology can occur in a benign cyst. Thus, this finding alone does not support an unequivocal diagnosis of malignancy.

60x

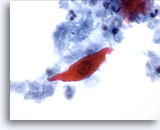

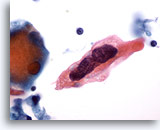

Figure 11

Neck FNA, suspicious for squamous carcinoma. A highly atypical squamous metaplastic cell is present. The cell is rounded and the cytoplasm contains keratin The nuclear membrane is irregular and the chromatin is separated into small discrete bundles. This type cell may lead to a strong recommendation that the lesion be excised. 60x

Neck FNA, suspicious for squamous carcinoma.

A highly atypical squamous metaplastic cell is present. The cell is rounded and the cytoplasm contains keratin. The nuclear membrane is irregular and the chromatin is separated into small discrete bundles. This type cell may lead to a strong recommendation that the lesion be excised.

60x

Figure 12

Neck FNA, suspicious for squamous carcinoma.

The central cell is a small metaplastic squamous cell with an enlarged oval nucleus with a smooth nuclear membrane. 60x

Neck FNA, suspicious for squamous carcinoma.

The central cell is a small metaplastic squamous cell with an enlarged oval nucleus with a smooth nuclear membrane.

60x

Figure 13

Neck FNA, suspicious for squamous carcinoma.

A large squamous cell with a large degenerated nucleus . Keratin filaments are near the periphery of the cell. 60x

Neck FNA, suspicious for squamous carcinoma.

A large squamous cell with a large degenerated nucleus . Keratin filaments are near the periphery of the cell.

60x

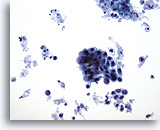

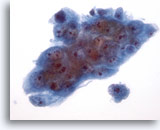

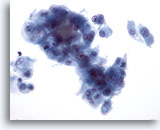

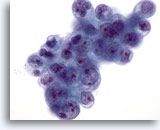

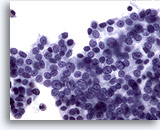

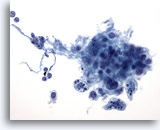

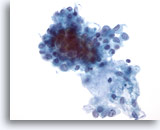

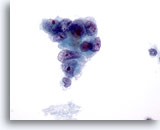

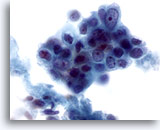

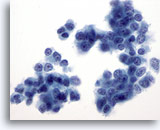

Figure 14

Neck FNA, poorly differentiated carcinoma. Two clusters of cells are noted. The large, irregular cluster has irregular borders and pleomorphic nuclei . The cells of the smaller group exhibit loss of cohesiveness and have an increased N/C ratio at this magnification. The background contains necrotic debris. 20x

Neck FNA, poorly differentiated carcinoma.

Two clusters of cells are noted. The large, irregular cluster has irregular borders and pleomorphic nuclei . The cells of the smaller group exhibit loss of cohesiveness and have an increased N/C ratio at this magnification. The background contains necrotic debris.

20x

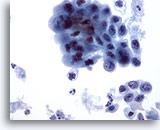

Figure 15

Neck FNA, poorly differentiated carcinoma.

The pleomorphism and hyperchromasia of the larger group of cells is clearer than at 20x. Neither the cytoplasmic nor the nuclear differentiation give evidence of the primary site. 40x

Neck FNA, poorly differentiated carcinoma.

The pleomorphism and hyperchromasia of the larger group of cells is clearer than at 20x. Neither the cytoplasmic nor the nuclear differentiation give evidence of the primary site.

40x

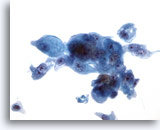

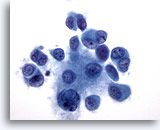

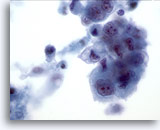

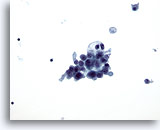

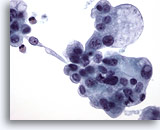

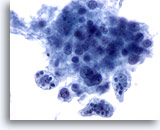

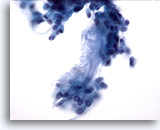

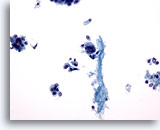

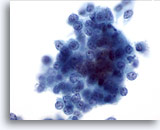

Figure 16

Neck FNA, poorly differentiated carcinoma.

This carcinoma clearly exhibits loss of cohesiveness. The nuclei are irregular and have clumping of chromatin. There is a large increase in the N/C ratio. Nucleoli are prominent and differ in number from cell to cell. 60x

Neck FNA, poorly differentiated carcinoma.

This carcinoma clearly exhibits loss of cohesiveness. The nuclei are irregular and have clumping of chromatin. There is a large increase in the N/C ratio. Nucleoli are prominent and differ in number from cell to cell.

60x

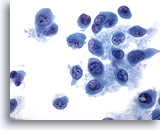

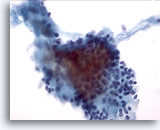

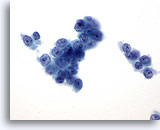

Figure 17

Neck FNA, poorly differentiated carcinoma.

This large cluster has all the primary characteristics of malignancy. Irregular nuclear membranes and notches can be plainly seen as well as clumping of chromatin and parachromatin clearing. 60x

Neck FNA, poorly differentiated carcinoma.

This large cluster has all the primary characteristics of malignancy. Irregular nuclear membranes and notches can be plainly seen as well as clumping of chromatin and parachromatin clearing.

60x

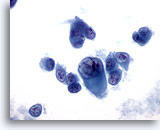

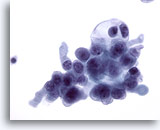

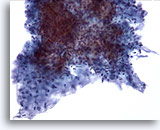

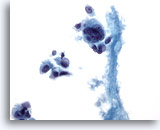

Figure 18

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

A large malignant cell is surrounded by small benign squamous cells, debris, inflammation and keratin. 20x

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

A large malignant cell is surrounded by small benign squamous cells, debris, inflammation and keratin.

20x

Figure 19

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

This malignant cell with a large, centrally placed nucleus has dense cyanophilic cytoplasm indicative of keratinzation and characteristic of a squamous cell. 40x

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

This malignant cell with a large, centrally placed nucleus has dense cyanophilic cytoplasm indicative of keratinzation and characteristic of a squamous cell.

40x

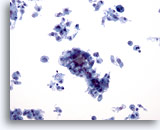

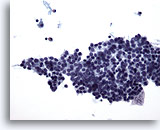

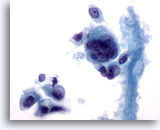

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma. This is a poorly differentiated malignancy and classification is helped by the fact that keratin is present in the background of malignant cells. (It is not uncommon to see both well-differentiated and poorly differentiated squamous cells in a FNA of the neck. The well-differentiated cells establish the identity.) There are two large clusters of cells and a necrotic background. 20x

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

This is a poorly differentiated malignancy and classification is helped by the fact that keratin is present in the background of malignant cells. (It is not uncommon to see both well-differentiated and poorly differentiated squamous cells in a FNA of the neck. The well-differentiated cells establish the identity.) There are two large clusters of cells and a necrotic background.

20x

Figure 21

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

Note the large, irregular nucleolus in the lower central area of the group of malignant cells. The nuclear membranes are outlined by the chromatin clumping. 40x

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

Note the large, irregular nucleolus in the lower central area of the group of malignant cells. The nuclear membranes are outlined by the chromatin clumping.

40x

Figure 22

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

Note the excellent preservation of the malignant cells. The nuclear detail is exquisite. 60x

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

Note the excellent preservation of the malignant cells. The nuclear detail is exquisite.

60x

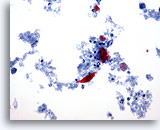

Figure 23

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma. The diagnosis is straightforward with the presence of a tadpole-shaped squamous cell with a cytologically malignant nucleus. Just above and to the right are two malignant squamous metaplastic cells. At the bottom right is another malignant squamous metaplastic cell. Tumor necrosis is present in the background. 20x

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

The diagnosis is straightforward with the presence of a tadpole-shaped squamous cell with a cytologically malignant nucleus. Just above and to the right are two malignant squamous metaplastic cells. At the bottom right is another malignant squamous metaplastic cell. Tumor necrosis is present in the background.

20x

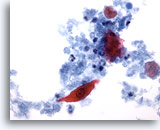

Figure 24

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

The malignant keratinizing tadpole-shaped squamous cell and the two malignant squamous metaplastic cells are clearly seen. Keratin is present and tumor necrosis surrounds the cells. 40x

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

The malignant keratinizing tadpole-shaped squamous cell and the two malignant squamous metaplastic cells are clearly seen. Keratin is present and tumor necrosis surrounds the cells.

40x

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma. In this photo there is an extremely large malignant cell. Note just above this cell are three lymphocytes which give an accurate size comparison of this huge cell. Additionally a scattering of other malignant cells along with some debris can also be seen. Squamous differentiation is evident in the smaller, orangeophilic cells that are in the field, and cling to the surface of this malignant cell. 20x

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

In this photo there is an extremely large malignant cell. Note just above this cell are three lymphocytes which give an accurate size comparison of this huge cell. Additionally a scattering of other malignant cells along with some debris can also be seen. Squamous differentiation is evident in the smaller, orangeophilic cells that are in the field, and cling to the surface of this malignant cell.

20x

Figure 26

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma. The large cell contrasts with the small lymphocytes in the photo. The small malignant squamous cell can be more clearly discerned. Above and to the right is a well formed malignant squamous cell with an intensely hyperchromatic nucleus and well defined thick cytoplasm. 40x

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

The large cell contrasts with the small lymphocytes in the photo. The small malignant squamous cell can be more clearly discerned. Above and to the right is a well formed malignant squamous cell with an intensely hyperchromatic nucleus and well defined thick cytoplasm.

40x

Figure 27

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

A huge malignant squamous cell is clearly portrayed. Again note the two lymphocytes in the photo. The nuclear chromatin appears raked in this photo. There is almost a three dimensional feel to this cell. 60x

Neck FNA, squamous cell carcinoma.

A huge malignant squamous cell is clearly portrayed. Again note the two lymphocytes in the photo. The nuclear chromatin appears raked in this photo. There is almost a three dimensional feel to this cell.

60x

Figure 28

Parotid FNA, high grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Cytologic criteria lead to a diagnosis of a poorly differentiated carcinoma. 40x

Parotid FNA, high grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Cytologic criteria lead to a diagnosis of a poorly differentiated carcinoma.

40x

Figure 29

Parotid FNA, high grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Intracellular mucin was demonstrated by mucicarmine stains. 40x

Parotid FNA, high grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Intracellular mucin was demonstrated by mucicarmine stains.

40x

Figure 30

Parotid FNA, high grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

A malignant population of squamous cells was present. 40x

Parotid FNA, high grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

A malignant population of squamous cells was present.

40x

Figure 31

Parotid FNA, high grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

A malignant cell adjacent to benign salivary tissue pinpoints the tumor location. 40x

Parotid FNA, high grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

A malignant cell adjacent to benign salivary tissue pinpoints the tumor location.

40x

Figure 32

Parotid FNA, suspicious for low grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Benign appearing salivary gland tissue, debris and mucin are apparent at low power. 20x

Parotid FNA, suspicious for low grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Benign appearing salivary gland tissue, debris and mucin are apparent at low power.

20x

Figure 33

Parotid FNA, suspicious for low grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Small nucleoli are present in the otherwise bland nuclei of cell clusters. 40x

Parotid FNA, suspicious for low grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Small nucleoli are present in the otherwise bland nuclei of cell clusters.

40x

Figure 34

Parotid FNA, suspicious for low grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Many single cells are floating in a mucinous background. The differential diagnosis includes a mucocele. 40x

Parotid FNA, suspicious for low grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Many single cells are floating in a mucinous background. The differential diagnosis includes a mucocele.

40x

Figure 35

Parotid FNA, suspicious for low grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

If the mucin is not noticed a benign diagnosis may be rendered causing a false negative. 40x

Parotid FNA, suspicious for low grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

If the mucin is not noticed a benign diagnosis may be rendered causing a false negative.

40x

Figure 36

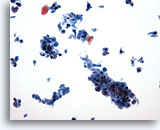

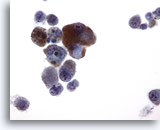

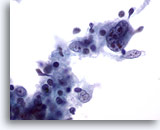

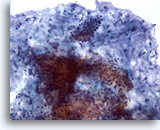

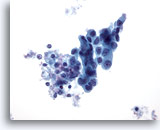

Neck FNA, malignant melanoma.

In this photo there are many single cells, and clusters of cells that contain pigment. In the center is a single plasmacytoid malignant cell, as well as naked nuclei. 20x

Neck FNA, malignant melanoma.

In this photo there are many single cells, and clusters of cells that contain pigment. In the center is a single plasmacytoid malignant cell, as well as naked nuclei.

20x

Figure 37

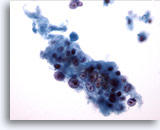

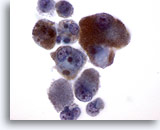

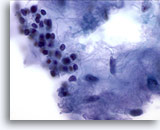

Neck FNA, malignant melanoma.

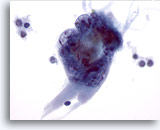

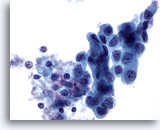

The two cell clusters seen at 20x contain brown melanin that distinguishes this as melanoma. The cell below is distinctly plasmacytoid with an oval nucleus and single nucleolus. 60x

Neck FNA, malignant melanoma.

The two cell clusters seen at 20x contain brown melanin that distinguishes this as melanoma. The cell below is distinctly plasmacytoid with an oval nucleus and single nucleolus.

60x

Figure 38

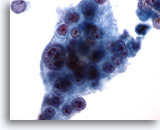

Neck FNA, malignant melanoma. Melanoma is a great mimicker of other malignancies. In this photo there is a group of loosely cohesive cells that are malignant, but whose identity would be obscure except that there is abundant cytoplasmic melanin. Note the excellent preservation of the cells and of the melanin granules. 60x

Neck FNA, malignant melanoma.

Melanoma is a great mimicker of other malignancies. In this photo there is a group of loosely cohesive cells that are malignant, but whose identity would be obscure except that there is abundant cytoplasmic melanin. Note the excellent preservation of the cells and of the melanin granules.

60x

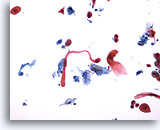

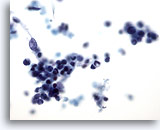

Axillary lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

There is a pleomorphic aggregate of single cells in this photo. Brownish pigment can be clearly discerned even at this magnification, especially in the center of the photo. Just below the bi-nucleated cell on the right is a plasmacytoid cell with a huge nucleolus. Even at this power the diagnosis of melanoma is easily made.

20x

Figure 40

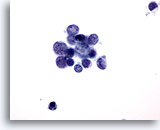

Axillary lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

The fine granularity of melanin and its coloration are easily appreciated at this magnification. The nuclei are eccentric with prominent nucleoli. The cells are single. 40x

Axillary lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

The fine granularity of melanin and its coloration are easily appreciated at this magnification. The nuclei are eccentric with prominent nucleoli. The cells are single.

40x

Figure 41

Axillary lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

The same cluster at higher magnification. Please note the characteristics of melanin. It is ideally represented in these malignant cells. 60x

Axillary lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

The same cluster at higher magnification. Please note the characteristics of melanin. It is ideally represented in these malignant cells.

60x

Figure 42

Axillary lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

A multinucleated giant melanoma cell is present. 60x

Axillary lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

A multinucleated giant melanoma cell is present.

60x

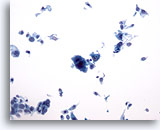

Figure 43

Lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

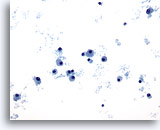

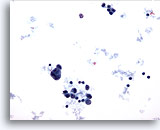

At this power there are three small groups of cells. Interspersed are numerous single cells with no cytoplasm or minimal cytoplasm. The pleomorphism and hyperchromasia strongly suggest malignancy but the type is not suggested. 20x

Lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

At this power there are three small groups of cells. Interspersed are numerous single cells with no cytoplasm or minimal cytoplasm. The pleomorphism and hyperchromasia strongly suggest malignancy but the type is not suggested.

20x

Figure 44

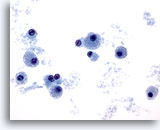

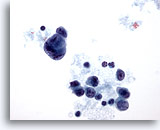

Lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma. Three cells have well defined cytoplasm. The rest seem to have almost a syncytial cytoplasm. The nuclei give no evidence as to site of origin. The three cells with the well defined cytoplasm could be called plasmacytoid and give a hint as to source of the primary. 40x

Lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

Three cells have well defined cytoplasm. The rest seem to have almost a syncytial cytoplasm. The nuclei give no evidence as to site of origin. The three cells with the well defined cytoplasm could be called plasmacytoid and give a hint as to source of the primary.

40x

Figure 45

Lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

A higher magnification reflecting the same characteristics as the prior photo. 60x

Lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

A higher magnification reflecting the same characteristics as the prior photo.

60x

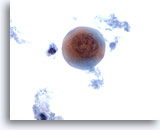

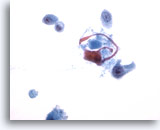

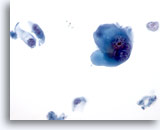

Figure 46

Lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

The cell lower right corner demonstrates an intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion a feature that is characteristic of, but not diagnostic for, malignant melanoma. 60x

Lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

The cell in the lower right corner demonstrates an intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion a feature that is characteristic of, but not diagnostic for, malignant melanoma.

60x

Figure 47

Lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

An intranuclear inclusion is present in the large plasmacytoid malignant cell and a huge nucleolus is present in a second malignant cell. Both are features of melanoma. 60x

Lymph node FNA, malignant melanoma.

An intranuclear inclusion is present in the large plasmacytoid malignant cell and a huge nucleolus is present in a second malignant cell. Both are features of melanoma.

60x

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic carcinoma consistent with lung primary.

The cell cluster in the middle of the slide is sufficient for the diagnosis of carcinoma, but the identification of the primary depends on additional clinical evaluation. Around the large group are cells with eccentric cytoplasm (plasmacytoid). The cohesive group coupled with these cells is consistent with lung carcinoma.

20x

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic lung carcinoma.

The cohesive group is a three dimensional configuration consistent with adenocarcinoma, lung primary.

40x

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic lung carcinoma.

The cohesive group is a three dimensional configuration consistent with adenocarcinoma, lung primary.

40x

Figure 50

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic lung carcinoma.

Note the cell in the center with a cytoplasmic vacuole and a single spot of mucin in its centrum. These features are consistent with primary lung adenocarcinoma. 60x

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic lung carcinoma.

Note the cell in the center with a cytoplasmic vacuole and a single spot of mucin in its centrum. These features are consistent with primary lung adenocarcinoma.

60x

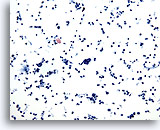

Figure 51

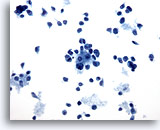

Supraclavicular lymph node FNA, small cell undifferentiated carcinoma. A very cellular specimen is pictured with a few clusters. The cells are slightly larger than a lymphocyte and are hyperchromatic. No cytoplasm can be seen. This pattern is consistent with small cell carcinoma. 20x

Supraclavicular lymph node FNA, small cell undifferentiated carcinoma.

A very cellular specimen is pictured with a few clusters. The cells are slightly larger than a lymphocyte and are hyperchromatic. No cytoplasm can be seen. This pattern is consistent with small cell carcinoma .

20x

Figure 52

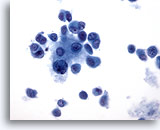

Supraclavicular lymph node FNA, small cell undifferentiated carcinoma.

The group in the center exhibits nuclear molding. The mild pleomorphism, the marked increase in N/C ratio and the lack of nucleoli all point to small cell carcinoma. 60x

Supraclavicular lymph node FNA, small cell undifferentiated carcinoma.

The group in the center exhibits nuclear molding. The mild pleomorphism, the marked increase in N/C ratio and the lack of nucleoli all point to small cell carcinoma.

60x

Figure 53

Supraclavicular lymph node FNA, small cell undifferentiated carcinoma.

Notice the lack of crush artifact. The cells are well preserved and again have all the features of small cell carcinoma. 60x

Supraclavicular lymph node FNA, small cell undifferentiated carcinoma.

Notice the lack of crush artifact. The cells are well preserved and again have all the features of small cell carcinoma.

60x

Figure 54

Lymph node FNA, metastatic endometrial adenocarcinoma.

This would be a staging FNA. It would not commonly be for an unsuspected tumor workup. Two large clusters of tightly cohesive cells that do not belong in a lymph node are present, thus establishing metastatic carcinoma. 20x

Lymph node FNA, metastatic endometrial adenocarcinoma.

This would be a staging FNA. It would not commonly be for an unsuspected tumor workup. Two large clusters of tightly cohesive cells that do not belong in a lymph node are present, thus establishing metastatic carcinoma.

20x

Figure 55

Lymph node FNA, metastatic endometrial adenocarcinoma.

The cluster in the lower half of the photo has pleomorphic nuclei with prominent nucleoli and nuclear material plastered against the nuclear membrane. The N/C ratio is high. 40x

Lymph node FNA, metastatic endometrial adenocarcinoma.

The cluster in the lower half of the photo has pleomorphic nuclei with prominent nucleoli and nuclear material plastered against the nuclear membrane. The N/C ratio is high.

40x

Figure 56

Lymph node FNA, metastatic endometrial adenocarcinoma.

The ball like feel to the cluster is present and the clarity of the cells is impressive. Note the clearing of the nuclear material, as it all seems to be located on the nuclear membrane. 60x

Lymph node FNA, metastatic endometrial adenocarcinoma.

The ball like feel to the cluster is present and the clarity of the cells is impressive. Note the clearing of the nuclear material, as it all seems to be located on the nuclear membrane.

60x

Figure 57

Lymph node FNA, metastatic endometrial adenocarcinoma.

This sheet of malignant cells again shows the same nuclear features and also displays cytoplasmic vacuolization. Note the irregularity of the nuclear membranes and prominent nucleoli that can be seen in this photo. 60x

Lymph node FNA, metastatic endometrial adenocarcinoma.

This sheet of malignant cells again shows the same nuclear features and also displays cytoplasmic vacuolization. Note the irregularity of the nuclear membranes and prominent nucleoli that can be seen in this photo.

60x

Figure 58

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid.

An irregular cohesive cluster of cells within a lymph node establishes the diagnosis of carcinoma. 20x

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid.

An irregular cohesive cluster of cells within a lymph node establishes the diagnosis of carcinoma.

20x

Figure 59

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid.

These malignant cells, while showing hyperchromasia, nucleoli, increased N/C ratio and clumping of chromatin, give no indication as to the primary site. 40x

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid.

These malignant cells, while showing hyperchromasia, nucleoli, increased N/C ratio and clumping of chromatin, give no indication as to the primary site.

40x

Figure 60

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. A large cohesive cluster of cells is present. The cells are mildly hyperchromatic and have some cytoplasm. Minimal pleomorphism is present. The diagnosis of carcinoma is established because this is a cohesive cell group is within a lymph node. 20x

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid.

A large cohesive cluster of cells is present. The cells are mildly hyperchromatic and have some cytoplasm. Minimal pleomorphism is present. The diagnosis of carcinoma is established because this is a cohesive cell group is within a lymph node.

20x

Figure 61

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. Notice the blandness of the nuclear chromatin which is characteristic of papillary thyroid carcinoma. An intra-cytoplasmic inclusion is present within one nucleus. At this magnification there is more pleomorphism than was seen at the lower power. 40x

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid.

Notice the blandness of the nuclear chromatin which is characteristic of papillary thyroid carcinoma. An intra-cytoplasmic inclusion is present within one nucleus. At this magnification there is more pleomorphism than was seen at the lower power.

40x

Figure 62

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid.

The nucleus with one intranuclear inclusion, the blandness of the nuclei and small nucleoli all are consistent with a papillary carcinoma metastasis. 40x

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid.

The nucleus with one intranuclear inclusion, the blandness of the nuclei and small nucleoli all are consistent with a papillary carcinoma metastasis.

40x

Figure 63

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid.

A large intranuclear inclusion is present. 60x

Neck lymph node FNA, metastatic papillary carcinoma of the thyroid.

A large intranuclear inclusion is present.

60x

Figure 64

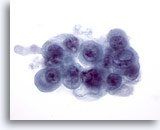

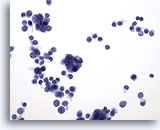

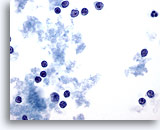

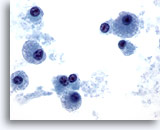

Lymph node FNA, reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. A FNA of a lymph node may yield small irregular clusters of macrophages and lymphocytes. These should not be misinterpreted as an epithelial neoplasm. There are two such clusters here along with many other small round cells of varying sizes. 20x

Lymph node FNA, reactive lymphoid hyperplasia.

A FNA of a lymph node may yield small irregular clusters of macrophages and lymphocytes. These should not be misinterpreted as an epithelial neoplasm. There are two such clusters here along with many other small round cells of varying sizes.

20x

Figure 65

Lymph node FNA, reactive.

One cluster contains macrophages with intracytoplasmic pigment, so called tingible body macrophages. 40x

Lymph node FNA, reactive.

One cluster contains macrophages with intracytoplasmic pigment, so called tingible body macrophages.

40x

Figure 66

Lymph node FNA, reactive.

The three tingible body macrophages are shown at high magnification. 60x

Lymph node FNA, reactive.

The three tingible body macrophages are shown at high magnification.

60x

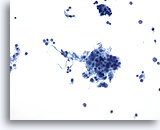

Figure 67

Lymph node FNA, reactive. There is a range of maturation of lymphocytes seen. Small mature lymphocytes, slightly larger and very large lymphocytes are present. A mitotic nucleus can be seen. Tingible body macrophages and a range of maturation make the diagnosis of reactive hyperplasia. 60x

Lymph node FNA, reactive.

There is a range of maturation of lymphocytes seen. Small mature lymphocytes, slightly larger and very large lymphocytes are present. A mitotic nucleus can be seen. Tingible body macrophages and a range of maturation make the diagnosis of reactive hyperplasia.

60x

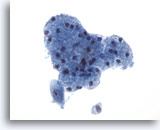

Figure 68

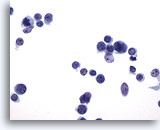

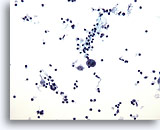

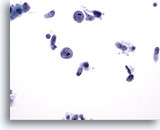

Lymph node FNA, atypical lymphoid proliferation.

The specimen is cellular and when compared to small lymphocyte a the majority of cells are slightly larger than this cell. The monotony of the sample is worrisome. 20x

Lymph node FNA, atypical lymphoid proliferation.

The specimen is cellular and when compared to a small lymphocyte the majority of cells are slightly larger than this cell. The monotony of the sample is worrisome.

20x

Figure 69

Lymph node FNA, atypical lymphoid proliferation.

Once again when a small lymphocyte is picked out, the majority of cells are larger. There is no range of maturity in this specimen. 40x

Lymph node FNA, atypical lymphoid proliferation.

Once again when a small lymphocyte is picked out, the majority of cells are larger. There is no range of maturity in this specimen.

40x

Figure 70

Lymph node FNA, atypical lymphoid proliferation.

A beautiful preparation. The nuclei are all oval with no nicks or cuts. The nucleoli are small and not hyperchromatic. 60x

Lymph node FNA, atypical lymphoid proliferation.

A beautiful preparation. The nuclei are all oval with no nicks or cuts. The nucleoli are small and not hyperchromatic.

60x

Figure 71

Lymph node FNA, atypical lymphoid proliferation.

Monotony, e.g. similar sized lymphocytes and the lack of tingible body macrophages, are the features of this atypical lymphoid proliferation. 60x

Lymph node FNA, atypical lymphoid proliferation.

Monotony, e.g. similar sized lymphocytes and the lack of tingible body macrophages, are the features of this atypical lymphoid proliferation.

60x

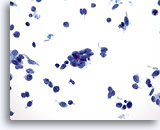

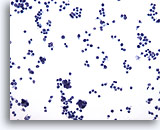

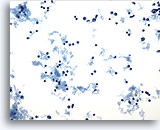

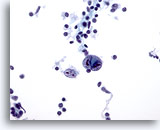

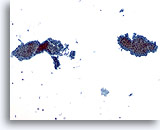

Figure 72

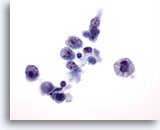

Lymph node FNA, malignant lymphoma.

This specimen is cellular with all cells scattered throughout the photo. Compare a small mature lymphocyte with the vast majority of the rest of the cells that are slightly enlarged. 20x

Lymph node FNA, malignant lymphoma.

This specimen is cellular with all cells scattered throughout the photo. Compare a small mature lymphocyte with the vast majority of the rest of the cells that are slightly enlarged.

20x

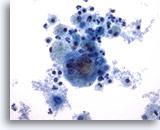

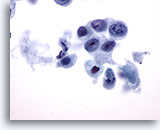

Figure 73

Lymph node FNA, malignant lymphoma.

At this magnification, irregularities can be seen in the nuclei and large red nucleoli are present in the majority of cells. All these cells are roughly the same size and are larger than the mature lymphocyte in the lower right corner. 40x

Lymph node FNA, malignant lymphoma.

At this magnification, irregularities can be seen in the nuclei and large red nucleoli are present in the majority of cells. All these cells are roughly the same size and are larger than the mature lymphocyte in the lower right corner.

40x

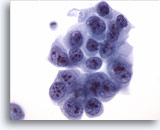

Figure 74

Lymph node FNA, malignant lymphoma.

Higher magnification exhibits the same features but with more clarity.

60x

Lymph node FNA, malignant lymphoma.

Higher magnification exhibits the same features but with more clarity.

60x

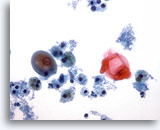

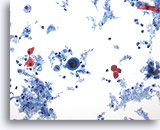

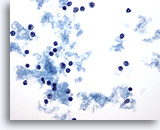

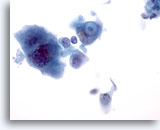

Figure 75

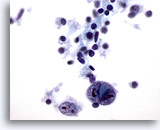

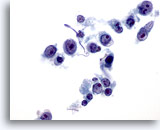

Lymph node FNA, Hodgkin’s disease.

A cellular specimen is pictured with the vast majority of cells being small round lymphocytes, but with two large bizarre cells that at this magnification are consistent with Reed-Sternberg cells. 20x

Lymph node FNA, Hodgkin’s disease.

A cellular specimen is pictured with the vast majority of cells being small round lymphocytes, but with two large bizarre cells that at this magnification are consistent with Reed-Sternberg cells.

20x

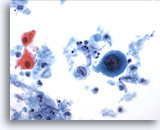

Figure 76

Lymph node FNA, Hodgkin’s disease.

Classic Reed Sternberg cells are diagnostic of Hodgkin’s disease with the associated characteristic background of inflammatory cells. 40x

Lymph node FNA, Hodgkin’s disease.

Classic Reed Sternberg cells are diagnostic of Hodgkin’s disease with the associated characteristic background of inflammatory cells.

40x

Figure 77

Lymph node FNA, Hodgkin’s disease.

The small lymphocytes present have no atypical features as would be expected. The two large bizarre cells have the « mirror image » features of Reed-Sternberg cells. 60x

Lymph node FNA, Hodgkin’s disease.

The small lymphocytes present have no atypical features as would be expected. The two large bizarre cells have the « mirror image » features of Reed-Sternberg cells.

60x

Figure 78

Lymph node FNA, Hodgkin’s disease.

A multinucleated, irregular, highly atypical cell is present. 60x

Lymph node FNA, Hodgkin’s disease.

A multinucleated, irregular, highly atypical cell is present.

60x

Figure 79

Lymph node FNA, Hodgkin’s disease.

Two large highly atypical cells are present. These are not diagnostic of Hodgkin’s disease but strongly suggest that the specimen should be carefully examined for more characteristic Reed-Sternberg cells. 60x

Lymph node FNA, Hodgkin’s disease.

Two large highly atypical cells are present. These are not diagnostic of Hodgkin’s disease but strongly suggest that the specimen should be carefully examined for more characteristic Reed-Sternberg cells.

60x

Figure 80

Neck FNA, plasmacytoma.

Single cells with abundant cytoplasm and an eccentric nucleus are present. 20x

Neck FNA, plasmacytoma.

Single cells with abundant cytoplasm and an eccentric nucleus are present.

20x

Figure 81

Neck FNA, plasmacytoma.

The nuclei are relatively small with smooth nuclear membranes and chromatin that is evenly dispersed. Small nucleoli are present in several of the cells. 40x

Neck FNA, plasmacytoma.

The nuclei are relatively small with smooth nuclear membranes and chromatin that is evenly dispersed. Small nucleoli are present in several of the cells.

40x

Figure 82

Neck FNA, plasmacytoma.

A higher magnification is shown here and it reflects the diagnosis of malignant plasma cells. 60x

Neck FNA, plasmacytoma.

A higher magnification is shown here and it reflects the diagnosis of malignant plasma cells.

60x

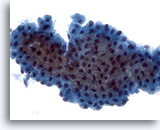

Figure 83

Parotid FNA, Warthin tumor (adenolymphoma).

Epithelial and lymphoid components of this benign neoplasm are seen at screening magnification. 10x

Parotid FNA, Warthin tumor (adenolymphoma).

Epithelial and lymphoid components of this benign neoplasm are seen at screening magnification.

10x

Figure 84

Parotid FNA, Warthin tumor (adenolymphoma).

Sheets of oxyphilic cells with abundant granular cytoplasm were present. 40x

Parotid FNA, Warthin tumor (adenolymphoma).

Sheets of oxyphilic cells with abundant granular cytoplasm were present.

40x

Figure 85

Parotid FNA, Warthin tumor (adenolymphoma).

Lymphocytes are admixed with oxyphilic cells in a background of amorphous debris. 95% of Warthin tumors occur in the parotid gland. 40x

Parotid FNA, Warthin tumor (adenolymphoma).

Lymphocytes are admixed with oxyphilic cells in a background of amorphous debris. 95% of Warthin tumors occur in the parotid gland.

40x

Figure 86

Salivary gland FNA, pleomorphic adenoma. At the central upper portion of the photo is an irregular grouping of epithelial cells with oval bland nuclei. Some have very tiny nucleoli. Immediately beneath this is stroma and a few single stromal cells. Pleomorphic adenoma is the most common salivary gland tumor. 40x

Salivary gland FNA, pleomorphic adenoma.

At the central upper portion of the photo is an irregular grouping of epithelial cells with oval bland nuclei. Some have very tiny nucleoli. Immediately beneath this is stroma and a few single stromal cells. Pleomorphic adenoma is the most common salivary gland tumor.

40x

Figure 87

Salivary gland FNA, pleomorphic adenoma.

The fibrillar nature of the stroma is clearly seen. There is a mixture of epithelium with stromal cells at the bottom of the stroma. 40x

Salivary gland FNA, pleomorphic adenoma.

The fibrillar nature of the stroma is clearly seen. There is a mixture of epithelium with stromal cells at the bottom of the stroma.

40x

Figure 88

Salivary gland FNA, pleomorphic adenoma.

Stroma can be seen both outside the cells (right side of the photo) and in intimate association with the cells. The epithelial nuclei appear organized and bland. 40x

Salivary gland FNA, pleomorphic adenoma.

Stroma can be seen both outside the cells (right side of the photo) and in intimate association with the cells. The epithelial nuclei appear organized and bland.

40x

Figure 89

Parotid FNA, pleomorphic adenoma.

In the center is a large cluster of crowded, difficult to see, epithelial cells. Those seen are bland. Around the epithelial cells is stroma in with embedded single stromal cells. The fibrillar nature of the stroma is appreciated. 20x

Parotid FNA, pleomorphic adenoma.

In the center is a large cluster of crowded, difficult to see, epithelial cells. Those seen are bland. Around the epithelial cells is stroma in with embedded single stromal cells. The fibrillar nature of the stroma is appreciated.

20x

Figure 90

Parotid FNA, pleomorphic adenoma.

Fibrillar stroma with epithelial cells is characteristic of pleomorphic adenoma. The association of epithelial cells and the fibrillar stroma is seen here. 20x

Parotid FNA, pleomorphic adenoma.

Fibrillar stroma with epithelial cells is characteristic of pleomorphic adenoma. The association of epithelial cells and the fibrillar stroma is seen here.

20x

Figure 91

Parotid FNA, pleomorphic adenoma.

Beautiful photo of the intimate association of epithelial cells, stromal cells and fibrillar stroma. Pleomorphic adenomas are slow growing tumors which may reoccur if not completely excised. 60x

Parotid FNA, pleomorphic adenoma.

Beautiful photo of the intimate association of epithelial cells, stromal cells and fibrillar stroma. Pleomorphic adenomas are slow growing tumors which may reoccur if not completely excised.

60x

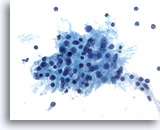

Figure 92

Parotid FNA, small cell carcinoma. When a small lymphocyte is picked out, the cluster of cells in the center and the smaller group just to the right of it both contain cells that are larger than the lymphocyte. Distinct hyperchromasia is present in both clusters. The background is necrotic. 20x

Parotid FNA, small cell carcinoma.

When a small lymphocyte is picked out, the cluster of cells in the center and the smaller group just to the right of it both contain cells that are larger than the lymphocyte. Distinct hyperchromasia is present in both clusters. The background is necrotic.

20x

Figure 93

Parotid FNA, small cell carcinoma.

The large cluster is a tightly bound, disordered group of cells. The nuclei are smudged and hyperchromatic. No cytoplasm is seen. 40x

Parotid FNA, small cell carcinoma.

The large cluster is a tightly bound, disordered group of cells. The nuclei are smudged and hyperchromatic. No cytoplasm is seen.

40x

Figure 94

Parotid FNA, small cell carcinoma.

The pleomorphism of small cell carcinoma is present here. Characteristic salt and pepper chromatin is present. No nucleoli are present. 60x

Parotid FNA, small cell carcinoma.

The pleomorphism of small cell carcinoma is present here. Characteristic salt and pepper chromatin is present. No nucleoli are present.

60x

Figure 95

Parotid FNA, lymphoma.

The specimen is cellular with a dirty background. Standing out are large single cells scattered within the photo. The cells are oval with minimal or no cytoplasm and have prominent nucleoli. 20x

Parotid FNA, lymphoma.

The specimen is cellular with a dirty background. Standing out are large single cells scattered within the photo. The cells are oval with minimal or no cytoplasm and have prominent nucleoli.

20x

Figure 96

Parotid FNA, lymphoma.

These large cells have minimal cytoplasm. One nucleus has a « bite » out of it. The nucleoli are large and not oval. 40x

Parotid FNA, lymphoma.

These large cells have minimal cytoplasm. One nucleus has a « bite » out of it. The nucleoli are large and not oval.

40x

Figure 97

Parotid FNA, lymphoma.

Single cells with large nuclei and large irregular nucleoli are present. The nuclear membranes are irregular. Minimal cytoplasm is present. A mitotic figure is shown. 60x

Parotid FNA, lymphoma.

Single cells with large nuclei and large irregular nucleoli are present. The nuclear membranes are irregular. Minimal cytoplasm is present. A mitotic figure is shown.

60x

Figure 98

Parotid FNA, lymphoma.

Large pleomorphic cells are arranged singly. Nuclei have nipples or noses. 60x

Parotid FNA, lymphoma.

Large pleomorphic cells are arranged singly. Nuclei have nipples or noses.

60x

Parotid FNA, lymphoma.

Single malignant cells are seen here.

60x

Figure 100

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma. A tight cluster of epithelial cells in the lymph node establishes that metastatic disease is present. The cells are large with irregular hyperchromatic nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Pleomorphism is marked. Nuclear membrane irregularity is present. 40x

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

A tight cluster of epithelial cells in the lymph node establishes that metastatic disease is present. The cells are large with irregular hyperchromatic nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Pleomorphism is marked. Nuclear membrane irregularity is present.

40x

Figure 101

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

Note the dense cytoplasm with a columnar look at the upper right corner. 60x

Figure 101

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

Note the dense cytoplasm with a columnar look at the upper right corner.

60x

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

Many cells that are not normal for a lymph node are present. Note the lymphocyte for size comparison. The largest cell is huge and clearly malignant. It appears to be a tumor giant cell at this power. A single cluster of cells is present in the upper portion that suggests the epithelial nature of this lesion. Several single cells with large nuclei and minimal cytoplasm are present in the lower portion of the photo.

20x

Figure 103

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

The tumor giant cell and the single malignant cells are more clearly visualized. 40x

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

The tumor giant cell and the single malignant cells are more clearly visualized.

40x

Figure 104

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

The epithelial nature of the malignancy is revealed by the clustering of the malignant cells. Notice the pleomorphism, marked irregularity of the nuclei and prominent nucleoli. 60x

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

The epithelial nature of the malignancy is revealed by the clustering of the malignant cells. Notice the pleomorphism, marked irregularity of the nuclei and prominent nucleoli.

60x

Figure 105

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

At the left is a cluster of epithelial cells that establishes the diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma. A tumor giant cell is present in the center. A scattering of other single malignant cells is present and the background is necrotic. 20x

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

At the left is a cluster of epithelial cells that establishes the diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma. A tumor giant cell is present in the center. A scattering of other single malignant cells is present and the background is necrotic.

20x

Figure 106

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

A closer look at the giant cell and the single malignant cell. 40x

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

A closer look at the giant cell and the single malignant cell.

40x

Figure 107

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

The tumor giant cell has large irregular nuclei. A slight plasmacytoid suggestion is present in some of the single cells. 60x

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

The tumor giant cell has large irregular nuclei. A slight plasmacytoid suggestion is present in some of the single cells.

60x

Figure 108

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

A cluster of malignant cells with the features of pleomorphism, nuclear membrane irregularity and mild hyperchromasia is present. Note the prominent nucleoli. 60x

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

A cluster of malignant cells with the features of pleomorphism, nuclear membrane irregularity and mild hyperchromasia is present. Note the prominent nucleoli.

60x

Figure 109

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma. Apart from the single cluster at the lower left, all the cells seen are arranged singly. By far the most impressive is the huge malignant giant cell in the center of the picture. However, note at its right, a nice plasmacytoid cell is also present. 20x

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

Apart from the single cluster at the lower left, all the cells seen are arranged singly. By far the most impressive is the huge malignant giant cell in the center of the picture. However, note at its right, a nice plasmacytoid cell is also present.

20x

Figure 110

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

A giant cell and the plasmacytoid cells are seen more clearly. 40x

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

A giant cell and the plasmacytoid cells are seen more clearly.

40x

Figure 111

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

The most important cell is the one in the center. A mucin drop in a vacuole is present in that malignant cell. 60x

Axillary lymph node FNA, metastatic breast carcinoma.

The most important cell is the one in the center. A mucin drop in a vacuole is present in that malignant cell.

60x

Figure 112

Thymus fine needle aspiration, atypical carcinoid.

At screening power the aspirate appears abundantly cellular. 20x

Thymus fine needle aspiration, atypical carcinoid.

At screening power the aspirate appears abundantly cellular.

20x

Figure 113

Thymus fine needle aspiration, atypical carcinoid.

Nuclei often display small nucleoli and stippled chromatin. 60x

Thymus fine needle aspiration, atypical carcinoid.

Nuclei often display small nucleoli and stippled chromatin.

60x

Figure 114

Thymus fine needle aspiration, atypical carcinoid.

Cells are arranged in small clusters or appear singly. 60x

Thymus fine needle aspiration, atypical carcinoid.

Cells are arranged in small clusters or appear singly.

60x

Figure 115

Thymus fine needle aspiration, atypical carcinoid.

Cytoplasm is scant to moderately abundant. 60x

Thymus fine needle aspiration, atypical carcinoid.

Cytoplasm is scant to moderately abundant.

60x