The breast is composed of fat and stroma that support glandular tissue, a branching ductal system that leads to 6-10 main ducts, which open onto the nipple. Both benign and malignant lesions develop in the breast. In young women fibroadenomas are common lesions but as women get older, fibrocystic changes tend to be more common. Other benign lesions include fat necrosis and inflammatory conditions such as breast abscess and mastitis. Less common benign lesions such as hamartomas and pseudoangiomatous hyperplasia can occur. Ductal hyperplasia forms part of fibrocystic changes. Atypical ductal hyperplasia can be difficult to distinguish from low grade ductal carcinoma in situ and these lesions represent a spectrum of disease that can develop into breast carcinoma. Radiation changes can produce a mass, which may appear atypical on aspiration cytology. Similarly, pregnancy and lactational changes can also be mistaken for malignancy on aspirates hence clinical information is essential for an accurate cytological diagnosis.

Malignancies in the breast may be primary or metastatic Those metastatic to the breast include lymphoma, malignant melanoma and other secondary tumors such as renal, bronchial, ovarian or pulmonary carcinomas. Most significant from a diagnostic perspective is primary breast carcinoma is the ductal type, not otherwise specified (NOS). The second most common primary mammary neoplasm is lobular carcinoma. Ductal carcinoma in situ and lobular carcinoma in situ are easily diagnosed on excision biopsies but are more difficult to diagnose with confidence on cytology.

Breast cytology has a role for both screening and diagnostic purposes. Any lesion detected on mammographic screening can be sampled with a fine needle, by direct aspiration if palpable or by stereotactic or ultrasound guidance if non-palpable. If the cytology sample is unsatisfactory or equivocal, core biopsy or frozen section can be utilized. Palpable breast masses are easily aspirated and can be quickly processed for a rapid diagnosis.

Fine-needle aspiration cytology is a useful tool in the diagnosis of breast lesions, both palpable and non-palpable. It is a safe, quick, inexpensive (as compared to core biopsies), and relatively painless procedure, and can be performed by clinicians as well as pathologists. In the hands of cytopathologists the inadequacy rate is low as rapid stains can be performed to evaluate specimen adequacy and the procedure repeated if necessary. Cyto-histological correlation is excellent in the hands of experienced cytopathologists. One minor disadvantage of fine-needle aspirates is that it is not always possible to distinguish between invasive and in situ lesions, but core biopsies too have similar problems in some cases.

The material aspirated is either smeared on a glass slide or expelled into Cytolyt® solution, and the needle is rinsed with the same solution for each pass made. The fluid can be used to make several almost identical slides thus enabling the lab to save material for special stains such as estrogen and progesterone receptors and HER2/neu protein over-expression.

There are also special types of ductal carcinoma that occur such as tubular, colloid (mucinous), metaplastic, medullary, apocrine and squamous. The definition of many of these special types of breast tumors is based on evidence that more than 90% of the lesion shows the typical characteristics of that type. As cytology samples only part of the tumor it is not accurate to categorize these tumors as tubular or mucinous cytologically. The suspicion can be raised in the report by including a description such as “ductal carcinoma with mucinous or tubular features” rather than a definite type, which might possibly differ from that of the excision specimen. Tubular carcinomas are composed of tubular and acinar structures. Mucinous carcinoma aspirates are often grossly mucoid and show abundant mucin on the smear. Certain rarities such as adenoid cystic carcinoma, identical to that seen in the salivary gland, may also develop. This tumor mimics benign collagenous spherulosis in that it also contains extracellular hyaline material with the same staining characteristics, but in the form of both globules and tubular or cylindrical structures. The accompanying tumor cells are small and bland with little cytoplasm, but benign ductal, apocrine and metaplastic cells are not seen.

Reminder: You may click on any slide image

for an enlarged view.

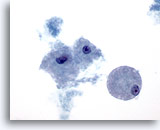

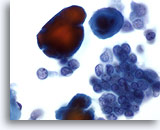

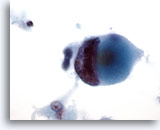

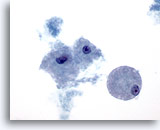

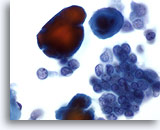

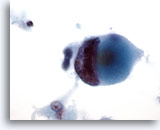

Figure 1

Breast FNA, Fat.

Fat cells, or adipocytes, are large spherical cells with translucent cytoplasm and small eccentric nuclei. They are seen in both benign and malignant aspirates. 40x

Figure 1

Breast FNA, Fat.

Fat cells, or adipocytes, are large spherical cells with translucent cytoplasm and small eccentric nuclei. They are seen in both benign and malignant aspirates.

40x

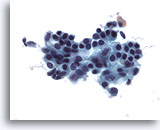

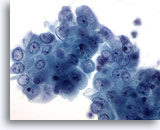

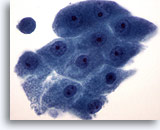

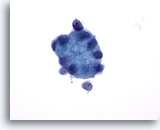

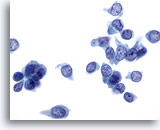

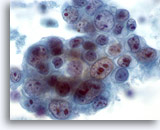

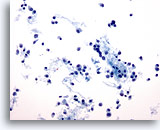

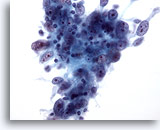

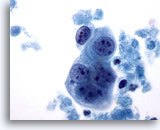

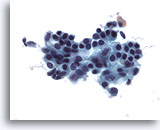

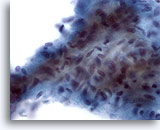

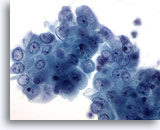

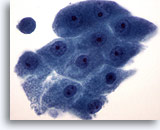

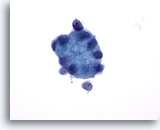

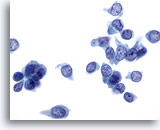

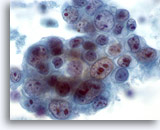

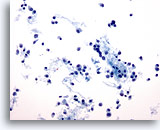

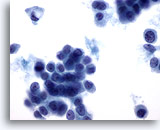

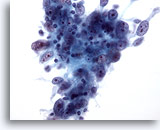

Figure 2

Breast FNA, Benign ductal cells.

Normal breast aspirates yield benign ductal cells, often accompanied by myoepithelial cells. 40x

Figure 2

Breast FNA, Benign ductal cells.

Normal breast aspirates yield benign ductal cells, often accompanied by myoepithelial cells.

40x

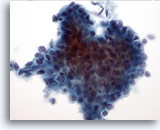

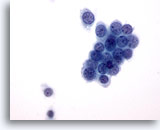

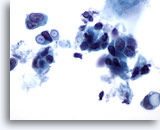

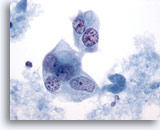

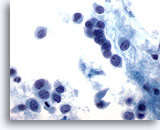

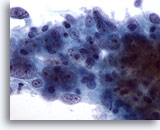

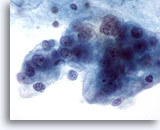

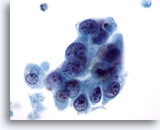

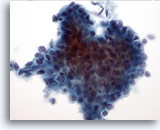

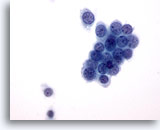

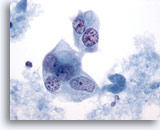

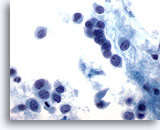

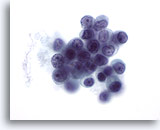

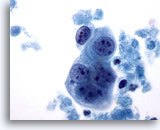

Figure 3

Breast FNA, Abscess.

Fine-needle aspirates of breast abscesses do not usually show epithelial cells. Cellular debris, lysed red cells and neutrophils are common features. 40x

Figure 3

Breast FNA, Abscess.

Fine-needle aspirates of breast abscesses do not usually show epithelial cells. Cellular debris, lysed red cells and neutrophils are common features.

40x

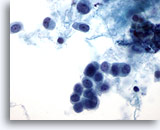

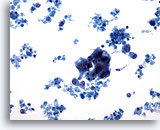

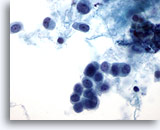

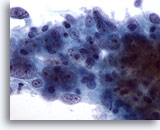

Figure 4: Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma. A large stromal fragment is present, containing a few small spindle-shaped nuclei. Stromal fragments may be seen in aspirates of benign breast tissue as well as in fibroepithelial lesions such as fibroadenoma. Stromal fragments from phyllodes tumors are much more cellular. Note the small group of benign ductal cells also present. 40x

Figure 4

Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma.

A large stromal fragment is present, containing a few small spindle-shaped nuclei. Stromal fragments may be seen in aspirates of benign breast tissue as well as in fibroepithelial lesions such as fibroadenoma. Stromal fragments from phyllodes tumors are much more cellular. Note the small group of benign ductal cells also present.

40x

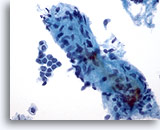

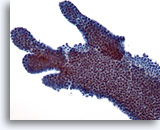

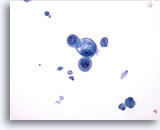

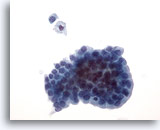

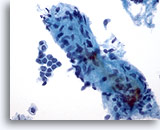

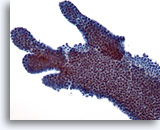

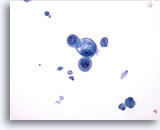

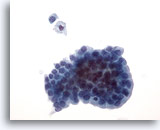

Figure 5

Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma.

A large branching sheet of cohesive, uniform benign ductal cells is seen overlying a stromal fragment. Note the small, somewhat spindled stromal cell nuclei within the stromal fragment. 20x

Figure 5

Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma.

A large branching sheet of cohesive, uniform benign ductal cells is seen overlying a stromal fragment. Note the small, somewhat spindled stromal cell nuclei within the stromal fragment.

20x

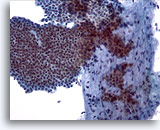

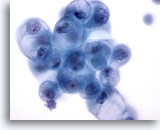

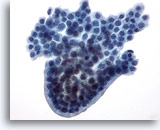

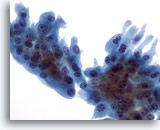

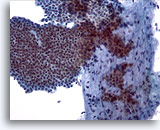

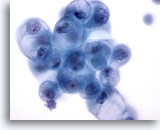

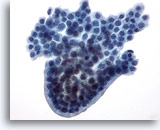

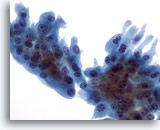

Figure 6

Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma.

Typically, fibroadenoma aspirates contain large branching sheets of benign ductal cells as seen in this illustration. 20x

Figure 6

Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma.

Typically, fibroadenoma aspirates contain large branching sheets of benign ductal cells as seen in this illustration.

20x

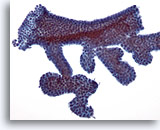

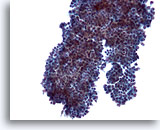

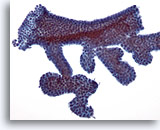

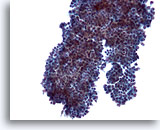

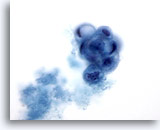

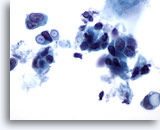

Figure 7

Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma.

This is another example of the branching appearance of ductal cells in fibroadenoma. 20x

Figure 7

Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma.

This is another example of the branching appearance of ductal cells in fibroadenoma.

20x

Figure 8

Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma.

In some instances the ductal cell groups have small rounded projections as seen here rather than the long branches noted in the prior two figures. 20x

Figure 8

Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma.

In some instances the ductal cell groups have small rounded projections as seen here rather than the long branches noted in the prior two figures.

20x

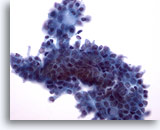

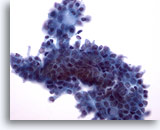

Figure 9: Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma. In this field the edges of the ductal group are not smooth as the previous two images above, possibly due to the liquid-based processing. Within the group of ductal cells, and at the upper edge, a few myoepithelial cells are noted. With ThinPrep processing myoepithelial cells tend to be seen adjacent to the ductal groups rather than scattered in the background as seen in conventional smears. 40x

Figure 9

Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma.

In this field the edges of the ductal group are not smooth as the previous two images above, possibly due to the liquid-based processing. Within the group of ductal cells, and at the upper edge, a few myoepithelial cells are noted. With ThinPrep processing myoepithelial cells tend to be seen adjacent to the ductal groups rather than scattered in the background as seen in conventional smears.

40x

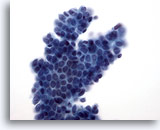

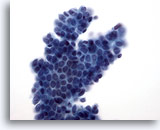

Figure 10

Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma.

A branching sheet of benign ductal cells with overlying myoepithelial cells produce the characteristic ‘sesame seed on a bun’ appearance. 40x

Figure 10

Breast FNA, Fibroadenoma.

A branching sheet of benign ductal cells with overlying myoepithelial cells produce the characteristic ‘sesame seed on a bun’ appearance.

40x

Figure 11: Breast FNA, Low grade phyllodes tumor. Phyllodes tumors are, like fibroadenomas, also fibroepithelial lesions. However even the low grade lesions have the capability of recurring if not excised with a wide margin. The glandular component is similar to that seen in fibroadenoma although it can be much more cellular and hyperplastic appearing. This illustration shows a three-dimensional group of ductal cells showing nuclear overlapping and crowding, suggestive of hyperplastic changes. 40x

Figure 11

Breast FNA, Low grade phyllodes tumor.

Phyllodes tumors are, like fibroadenomas, also fibroepithelial lesions. However even the low grade lesions have the capability of recurring if not excised with a wide margin. The glandular component is similar to that seen in fibroadenoma although it can be much more cellular and hyperplastic appearing. This illustration shows a three-dimensional group of ductal cells showing nuclear overlapping and crowding, suggestive of hyperplastic changes.

40x

Figure 12

Breast FNA, Low grade phyllodes tumor.

This stromal fragment is hypercellular and contains crowded plump spindle cells. Many single spindled stromal cells may also be seen in the background in this lesion. 60x

Figure 12

Breast FNA, Low grade phyllodes tumor.

This stromal fragment is hypercellular and contains crowded plump spindle cells. Many single spindled stromal cells may also be seen in the background in this lesion.

60x

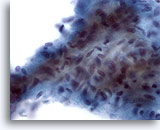

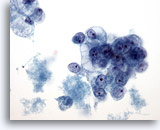

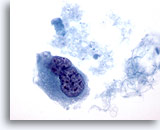

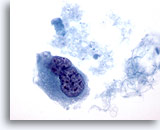

Figure 13

Breast FNA, Fibrocystic changes.

This field shows a tight cluster of benign ductal cells with foamy macrophages at each end, with secretory material in the background. 40x

Figure 13

Breast FNA, Fibrocystic changes.

This field shows a tight cluster of benign ductal cells with foamy macrophages at each end, with secretory material in the background.

40x

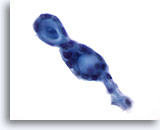

Figure 14

Breast FNA, Fibrocystic changes.

This small group of benign ductal cells is from an aspirate of fibrocystic changes. 40x

Figure 14

Breast FNA, Fibrocystic changes.

This small group of benign ductal cells is from an aspirate of fibrocystic changes.

40x

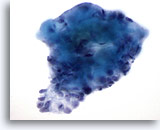

Figure 15

Breast FNA, Fibrocystic changes.

Background secretion, blood and apocrine metaplastic cells are seen in fibrocystic changes. 20x

Figure 15

Breast FNA, Fibrocystic changes.

Background secretion, blood and apocrine metaplastic cells are seen in fibrocystic changes.

20x

Figure 16

Breast FNA, Breast cyst.

This cluster of benign ductal cells shows mild atypia in the form of visible nucleoli and slight nuclear enlargement. Such minimal changes are often noted in breast cyst fluids. 60x

Figure 16

Breast FNA, Breast cyst.

This cluster of benign ductal cells shows mild atypia in the form of visible nucleoli and slight nuclear enlargement. Such minimal changes are often noted in breast cyst fluids.

60x

Figure 17

Breast FNA, Breast cyst.

This field shows a small group of benign epithelial cells, one vacuolated, with cyst debris in the background. 40x

Figure 17

Breast FNA, Breast cyst.

This field shows a small group of benign epithelial cells, one vacuolated, with cyst debris in the background.

40x

Figure 18

Breast FNA, Breast cyst.

Benign ductal cells in cyst fluid may show degenerative vacuolization as illustrated here. These changes should not be interpreted as being diagnostic of carcinoma. 60x

Figure 18

Breast FNA, Breast cyst.

Benign ductal cells in cyst fluid may show degenerative vacuolization as illustrated here. These changes should not be interpreted as being diagnostic of carcinoma.

60x

Figure 19

Breast FNA, Apocrine metaplasia.

Benign apocrine cells are often seen in flat sheets. They are commonly seen in breast cyst fluids and in fine-needle aspirates from areas of fibrocystic change. 40x

Figure 19

Breast FNA, Apocrine metaplasia.

Benign apocrine cells are often seen in flat sheets. They are commonly seen in breast cyst fluids and in fine-needle aspirates from areas of fibrocystic change.

40x

Figure 20

Breast FNA, Apocrine metaplasia.

Apocrine cells display abundant granular cytoplasm and round nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Their cytoplasmic borders are usually clearly defined. 60x

Figure 20

Breast FNA, Apocrine metaplasia.

Apocrine cells display abundant granular cytoplasm and round nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Their cytoplasmic borders are usually clearly defined.

60x

Figure 21: Breast FNA, Cystic papillary lesion. Aspirates from cystic papillary lesions contain epithelial cells as well as foamy macrophages. The benign ductal cells in this group are uniform in size and shape and display palisading along one edge. Note the foamy macrophage and single benign ductal cell above the group. If mild cellular atypia is present it can be difficult to distinguish a benign lesion from a malignant papillary lesion. 40x

Figure 21

Breast FNA, Cystic papillary lesion.

Aspirates from cystic papillary lesions contain epithelial cells as well as foamy macrophages. The benign ductal cells in this group are uniform in size and shape and display palisading along one edge. Note the foamy macrophage and single benign ductal cell above the group. If mild cellular atypia is present it can be difficult to distinguish a benign lesion from a malignant papillary lesion.

40x

Figure 22

Breast FNA, Cystic papillary lesion.

This group of benign ductal cells has a rounded, palisaded edge, giving the appearance of a papillary structure, although no fibrovascular core is seen. 40x

Figure 22

Breast FNA, Cystic papillary lesion.

This group of benign ductal cells has a rounded, palisaded edge, giving the appearance of a papillary structure, although no fibrovascular core is seen.

40x

Figure 23: Breast FNA, Cystic papillary lesion. A rounded papillary cluster of degenerating, vacuolated ductal cells is seen in this field, accompanied by secretory material. This appearance is best reported as atypical as it is not always possible to distinguish between benign and malignant papillary lesions. The presence of apocrine metaplastic cells is usually a clue to a benign process. 60x

Figure 23

Breast FNA, Cystic papillary lesion.

A rounded papillary cluster of degenerating, vacuolated ductal cells is seen in this field, accompanied by secretory material. This appearance is best reported as atypical as it is not always possible to distinguish between benign and malignant papillary lesions. The presence of apocrine metaplastic cells is usually a clue to a benign process.

60x

Figure 24

Breast FNA, Cystic papillary lesion.

Foamy macrophages, as illustrated here, are noted in both benign and malignant cystic lesions, whether papillary or not. 60x

Figure 24

Breast FNA, Cystic papillary lesion.

Foamy macrophages, as illustrated here, are noted in both benign and malignant cystic lesions, whether papillary or not.

60x

Figure 25: Breast FNA, Collagenous spherulosis. This is a benign lesion which is usually an incidental finding in breast biopsies. Rarely does it form a palpable mass. The aspirate contains evidence of benign ductal hyperplasia, benign ductal and apocrine metaplastic cells, myoepithelial cells, and globules of extracellular material surrounded by small benign epithelial cells. A similar picture is seen in aspirates from adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast. 60x

Figure 25

Breast FNA, Collagenous spherulosis.

This is a benign lesion which is usually an incidental finding in breast biopsies. Rarely does it form a palpable mass. The aspirate contains evidence of benign ductal hyperplasia, benign ductal and apocrine metaplastic cells, myoepithelial cells, and globules of extracellular material surrounded by small benign epithelial cells. A similar picture is seen in aspirates from adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast.

60x

Figure 26

Breast FNA, Collagenous spherulosis.

This large globule of hyaline material is surrounded by small epithelial cells. 60x

Figure 26

Breast FNA, Collagenous spherulosis.

This large globule of hyaline material is surrounded by small epithelial cells.

60x

Figure 27

Breast FNA, Collagenous spherulosis/apocrine metaplasia.

A sheet of apocrine metaplastic cells with relatively abundant cytoplasm was present in the aspirate of the case pictured above showing collagenous spherulosis. 40x

Figure 27

Breast FNA, Collagenous spherulosis/apocrine metaplasia.

A sheet of apocrine metaplastic cells with relatively abundant cytoplasm was present in the aspirate of the case pictured above showing collagenous spherulosis.

40x

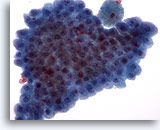

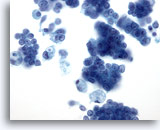

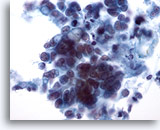

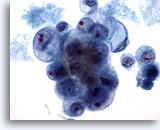

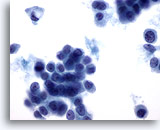

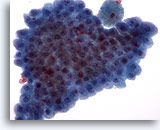

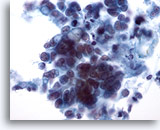

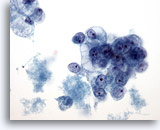

Figure 28: Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma in situ. This is a cellular aspirate showing clusters of tumor cells, single malignant cells and foamy macrophages. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) often shows myoepithelial cells overlying the malignant cell clusters. Tumor cells tend to be clustered rather than single as in invasive tumor. In addition, tubular structures are not associated with DCIS. Comedo DCIS is characteristically associated with necrosis and calcium. 40x

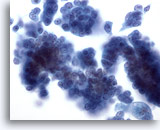

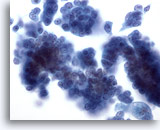

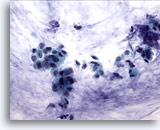

Figure 28

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma in situ.

This is a cellular aspirate showing clusters of tumor cells, single malignant cells and foamy macrophages. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) often shows myoepithelial cells overlying the malignant cell clusters. Tumor cells tend to be clustered rather than single as in invasive tumor. In addition, tubular structures are not associated with DCIS. Comedo DCIS is characteristically associated with necrosis and calcium.

40x

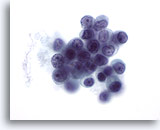

Figure 29

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma in situ.

Clusters of fairly bland tumor cells are noted. A vague impression of a fibrovascular core is noted in the cell group on the right. 40x

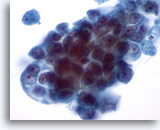

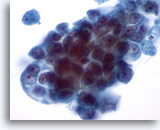

Figure 29

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma in situ.

Clusters of fairly bland tumor cells are noted. A vague impression of a fibrovascular core is noted in the cell group on the right.

40x

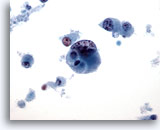

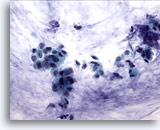

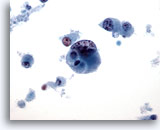

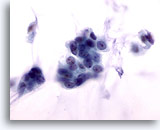

Figure 30

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma.

This low-power field shows abundant cellular necrosis with a tight cluster of cells in the center from a case of invasive ductal carcinoma. 20x

Figure 30

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma.

This low-power field shows abundant cellular necrosis with a tight cluster of cells in the center from a case of invasive ductal carcinoma.

20x

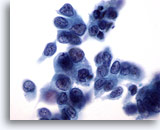

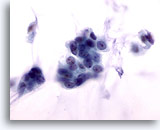

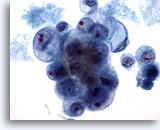

Figure 31

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma.

Under higher magnification the neoplastic cells show crowding and prominent nucleoli. The chromatin is abnormal though pale. 60x

Figure 31

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma.

Under higher magnification the neoplastic cells show crowding and prominent nucleoli. The chromatin is abnormal though pale.

60x

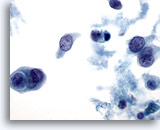

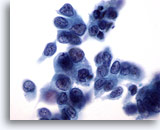

Figure 32

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma.

The tumor cells in this field show some dissociation, pleomorphism, nuclear irregularity, hyperchromasia and nucleoli. 60x

Figure 32

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma.

The tumor cells in this field show some dissociation, pleomorphism, nuclear irregularity, hyperchromasia and nucleoli.

60x

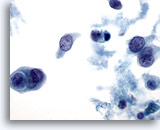

Figure 33

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma.

Necrosis, cannibalism within tumor cells and cell dissociation are illustrated in this image. 60x

Figure 33

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma.

Necrosis, cannibalism within tumor cells and cell dissociation are illustrated in this image.

60x

Figure 34

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, low grade. Carcinoma cells are seen here in clusters and singly, accompanied by calcium particles, which stain red with the Papanicoloau stain. The cells appear monomorphic, with smooth nuclear margins and micronucleoli, suggesting a low grade ductal carcinoma. 60x

Figure 34

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, low grade.

Carcinoma cells are seen here in clusters and singly, accompanied by calcium particles, which stain red with the Papanicoloau stain. The cells appear monomorphic, with smooth nuclear margins and micronucleoli, suggesting a low grade ductal carcinoma.

60x

Figure 35

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, low grade.

Many single carcinoma cells are seen in this field. The nuclei are pale but the chromatin pattern is distinctly abnormal. Nucleoli are not enlarged in this instance. 60x

Figure 35

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, low grade.

Many single carcinoma cells are seen in this field. The nuclei are pale but the chromatin pattern is distinctly abnormal. Nucleoli are not enlarged in this instance.

60x

Figure 36

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, low grade.

This is an example of a low grade ductal carcinoma. Some tumor cells are in a tight cluster with a few single cells. Note the round nuclear margins. 60x

Figure 36

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, low grade.

This is an example of a low grade ductal carcinoma. Some tumor cells are in a tight cluster with a few single cells. Note the round nuclear margins.

60x

Figure 37

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma.

This field shows tumor cells lying singly and in small clusters. Some cells appear to contain intracytoplasmic vacuoles. Nuclear size is variable within the clusters of cells. 40x

Figure 37

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma.

This field shows tumor cells lying singly and in small clusters. Some cells appear to contain intracytoplasmic vacuoles. Nuclear size is variable within the clusters of cells.

40x

Figure 38

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma. These malignant cells display clearly defined intracytoplasmic vacuoles, some of which are targetoid in appearance. Although this feature is usually described as being characteristic of lobular carcinoma, it may be seen in ductal carcinoma too. 60x

Figure 38

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma.

These malignant cells display clearly defined intracytoplasmic vacuoles, some of which are targetoid in appearance. Although this feature is usually described as being characteristic of lobular carcinoma, it may be seen in ductal carcinoma too.

60x

Figure 39

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, grade 2.

Clusters of vacuolated malignant cells are seen, with round nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Note the necrosis in the background. 40x

Figure 39

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, grade 2.

Clusters of vacuolated malignant cells are seen, with round nuclei and prominent nucleoli. Note the necrosis in the background.

40x

Figure 40

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, grade 2.

This is from the same case as Figure 39 above. The tumor cells show marked variation in nuclear and nucleolar size. Necrosis is present. The biopsy was reported as a moderately differentiated ductal carcinoma. 60x

Figure 40

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, grade 2.

This is from the same case as Figure 39 above. The tumor cells show marked variation in nuclear and nucleolar size. Necrosis is present. The biopsy was reported as a moderately differentiated ductal carcinoma.

60x

Figure 41

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, high grade. This field illustrates the variability in nuclear shape that can be seen in ductal carcinoma. Some nuclei are almost spindle-shaped. Most of the nuclei are much larger than the adjacent neutrophil and lymphocyte. The chromatin pattern shows clumping and clearing. 60x

Figure 41

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, high grade.

This field illustrates the variability in nuclear shape that can be seen in ductal carcinoma. Some nuclei are almost spindle-shaped. Most of the nuclei are much larger than the adjacent neutrophil and lymphocyte. The chromatin pattern shows clumping and clearing.

60x

Figure 42

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, high grade.

This is another example of pleomorphism in ductal carcinoma. This cluster of tumor cells contains nuclei of varying sizes. Some cells have multiple large nucleoli. Necrosis is seen in the background. 60x

Figure 42

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, high grade.

This is another example of pleomorphism in ductal carcinoma. This cluster of tumor cells contains nuclei of varying sizes. Some cells have multiple large nucleoli. Necrosis is seen in the background.

60x

Figure 43

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, high grade.

The malignant cells in this field are multinucleated with pale nuclei showing clumped and cleared chromatin. 60x

Figure 43

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, high grade.

The malignant cells in this field are multinucleated with pale nuclei showing clumped and cleared chromatin.

60x

Figure 44

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, high grade.

This is from the same case as Figure 43 above and shows a binucleated cell with hyperchromatic nuclei and clumped and cleared chromatin. 60x

Figure 44

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, high grade.

This is from the same case as Figure 43 above and shows a binucleated cell with hyperchromatic nuclei and clumped and cleared chromatin.

60x

Figure 45

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, high grade.

This is an example of a high grade, poorly differentiated ductal carcinoma. The cells are lying singly, abnormal chromatin and nucleoli are visible and there is cellular necrosis in the background. 40x

Figure 45

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, high grade.

This is an example of a high grade, poorly differentiated ductal carcinoma. The cells are lying singly, abnormal chromatin and nucleoli are visible and there is cellular necrosis in the background.

40x

Figure 46

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, high grade.

Note the marked clumping and clearing of chromatin in this malignant cell from the same case as in Figure 45 above.

Figure 46

Breast FNA, Ductal carcinoma, high grade.

Note the marked clumping and clearing of chromatin in this malignant cell from the same case as in Figure 45 above.

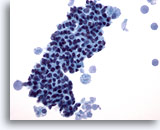

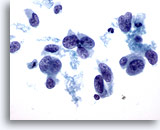

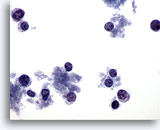

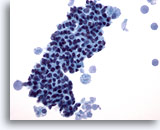

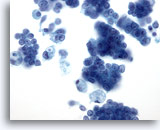

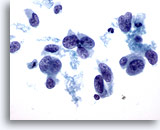

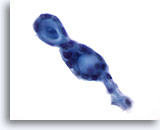

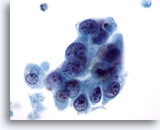

Figure 47

Breast FNA, Lobular carcinoma.

Lobular carcinoma aspirates tend to be sparsely cellular, but occasionally contain many cells as in this example. The tumor cells are single, but may form small aggregates, often with a single file appearance. 20x

Figure 47

Breast FNA, Lobular carcinoma.

Lobular carcinoma aspirates tend to be sparsely cellular, but occasionally contain many cells as in this example. The tumor cells are single, but may form small aggregates, often with a single file appearance.

20x

Figure 48

Breast FNA, Lobular carcinoma.

The neoplastic cells are usually small, with round to irregular nuclear margins and eccentric nuclei, producing a plasmacytoid appearance as illustrated in this field. 60x

Figure 48

Breast FNA, Lobular carcinoma.

The neoplastic cells are usually small, with round to irregular nuclear margins and eccentric nuclei, producing a plasmacytoid appearance as illustrated in this field.

60x

Figure 49

Breast FNA, Lobular carcinoma.

Cells with a plasmacytoid appearance and round nuclei are shown here. The background material appears to be proteinaceous in nature, rather than necrotic. A small single file of 3 cells is seen in the center of the field. 60x

Figure 49

Breast FNA, Lobular carcinoma.

Cells with a plasmacytoid appearance and round nuclei are shown here. The background material appears to be proteinaceous in nature, rather than necrotic. A small single file of 3 cells is seen in the center of the field.

60x

Figure 50

Breast FNA, Lobular carcinoma.

Intracytoplasmic vacuoles are commonly seen in lobular carcinoma aspirates, as seen in the single cell in the upper left of the field. Vacuoles are not exclusive to lobular carcinoma as they may also be seen in ductal carcinoma. 60x

Figure 50

Breast FNA, Lobular carcinoma.

Intracytoplasmic vacuoles are commonly seen in lobular carcinoma aspirates, as seen in the single cell in the upper left of the field. Vacuoles are not exclusive to lobular carcinoma as they may also be seen in ductal carcinoma.

60x

Figure 51

Breast FNA, Lobular carcinoma.

Although nucleoli are not a feature commonly seen in lobular carcinoma (except in pleomorphic lobular carcinoma), they may sometimes be noted. 60x

Figure 51

Breast FNA, Lobular carcinoma.

Although nucleoli are not a feature commonly seen in lobular carcinoma (except in pleomorphic lobular carcinoma), they may sometimes be noted.

60x

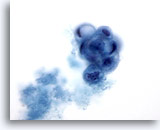

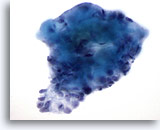

Figure 52

Breast FNA, Colloid (mucinous) carcinoma. Clusters of small cells and some single cells are shown in a background of mucin. It is preferable to report such cases as ductal carcinoma showing mucinous differentiation rather than colloid or mucinous carcinoma as the diagnosis is dependent upon the whole tumor showing mucin production. 40x

Figure 52

Breast FNA, Colloid (mucinous) carcinoma.

Clusters of small cells and some single cells are shown in a background of mucin. It is preferable to report such cases as ductal carcinoma showing mucinous differentiation rather than colloid or mucinous carcinoma as the diagnosis is dependent upon the whole tumor showing mucin production.

40x

Figure 53

Breast FNA, Colloid carcinoma.

The malignant cells in this lesion are bland, with smooth nuclear margins, evenly distributed chromatin and no visible nucleoli. If the mucin is not noted the cells may be misinterpreted as benign. 60x

Figure 53

Breast FNA, Colloid carcinoma.

The malignant cells in this lesion are bland, with smooth nuclear margins, evenly distributed chromatin and no visible nucleoli. If the mucin is not noted the cells may be misinterpreted as benign.

60x

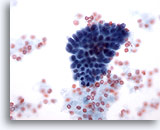

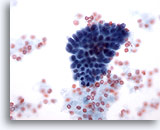

Figure 54

Breast FNA, Medullary carcinoma.

Fine-needle aspirates from these tumors typically show clusters of large pleomorphic tumor cells with prominent nucleoli, admixed with lymphocytes as seen here. Plasma cells may also be seen. 40x

Figure 54

Breast FNA, Medullary carcinoma.

Fine-needle aspirates from these tumors typically show clusters of large pleomorphic tumor cells with prominent nucleoli, admixed with lymphocytes as seen here. Plasma cells may also be seen.

40x

Figure 55

Breast FNA, Medullary carcinoma.

This cluster of cells shows large central nucleoli and abnormal chromatin. Lymphocytes are also noted. 60x

Figure 55

Breast FNA, Medullary carcinoma.

This cluster of cells shows large central nucleoli and abnormal chromatin. Lymphocytes are also noted.

60x

Figure 56

Breast FNA, Adenoid cystic carcinoma.

These tumors characteristically contain extracellular hyaline material in globular or cylindrical/tubular forms, surrounded by small, bland neoplastic cells. In this field two adjacent globular structures are seen. 60x

Figure 56

Breast FNA, Adenoid cystic carcinoma.

These tumors characteristically contain extracellular hyaline material in globular or cylindrical/tubular forms, surrounded by small, bland neoplastic cells. In this field two adjacent globular structures are seen.

60x

Figure 57

Breast FNA, Adenoid cystic carcinoma.

Here extracellular hyaline material is well illustrated, forming a vague tubule with two attached globular structures. 20x

Figure 57

Breast FNA, Adenoid cystic carcinoma.

Here extracellular hyaline material is well illustrated, forming a vague tubule with two attached globular structures.

20x

Figure 58

Breast FNA, Adenoid cystic carcinoma. This field illustrates a collection of hyaline globules with overlying small tumor cells. The differential diagnosis is collagenous spherulosis, a benign lesion in which the hyaline globules are accompanied by benign or hyperplastic ductal cells. 60x

Figure 58

Breast FNA, Adenoid cystic carcinoma.

This field illustrates a collection of hyaline globules with overlying small tumor cells. The differential diagnosis is collagenous spherulosis, a benign lesion in which the hyaline globules are accompanied by benign or hyperplastic ductal cells.

60x

Figure 59

Breast FNA, Malignant cyst.

Not all cysts are benign. Some ductal carcinomas can present as cystic lesions as in this example. The low power view shows proteinaceous material, blood and a cluster of hyperchromatic cells. 20x

Figure 59

Breast FNA, Malignant cyst.

Not all cysts are benign. Some ductal carcinomas can present as cystic lesions as in this example. The low power view shows proteinaceous material, blood and a cluster of hyperchromatic cells.

20x

Figure 60

Breast FNA, Malignant cyst.

On high power the cluster of cells seen in Figure 59 above shows pleomorphism, visible nucleoli and vacuolation. The excision biopsy showed ductal carcinoma. 60x

Figure 60

Breast FNA, Malignant cyst.

On high power the cluster of cells seen in Figure 59 above shows pleomorphism, visible nucleoli and vacuolation. The excision biopsy showed ductal carcinoma.

60x

Figure 61

Breast FNA, Malignant cyst.

This is another example of ductal carcinoma diagnosed on a cyst aspirate. This field shows markedly pleomorphic, vacuolated malignant cells with nucleoli and abnormal chromatin. 60x

Figure 61

Breast FNA, Malignant cyst.

This is another example of ductal carcinoma diagnosed on a cyst aspirate. This field shows markedly pleomorphic, vacuolated malignant cells with nucleoli and abnormal chromatin.

60x

Figure 62

Breast FNA, Malignant cyst.

This field shows a hyperchromatic cluster of epithelial cells with much cellular debris in the background, suspicious for carcinoma. 20x

Figure 62

Breast FNA, Malignant cyst.

This field shows a hyperchromatic cluster of epithelial cells with much cellular debris in the background, suspicious for carcinoma.

20x

Figure 63

Breast FNA, Malignant cyst.

A small group of tumor cells is seen here, with prominent nucleoli and fairly smooth nuclear margins. Note the surrounding necrosis. 60x

Figure 63

Breast FNA, Malignant cyst.

A small group of tumor cells is seen here, with prominent nucleoli and fairly smooth nuclear margins. Note the surrounding necrosis.

60x

Figure 64

Breast FNA, Malignant cyst.

This is from the same case as Figure 63 above. The cells show overlapping but also a hint of separation, irregular nuclear margins, abnormal chromatin and visible nucleoli. 60x

Figure 64

Breast FNA, Malignant cyst.

This is from the same case as Figure 63 above. The cells show overlapping but also a hint of separation, irregular nuclear margins, abnormal chromatin and visible nucleoli.

60x

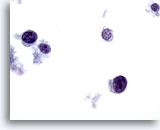

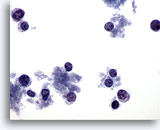

Figure 65

Breast FNA, Lymphoma.

This field shows scattered cells with very little cytoplasm. No clusters are present. The cells have round nuclei with a margin of cytoplasm at one side. The features appear lymphoid rather than epithelial. 40x

Figure 65

Breast FNA, Lymphoma.

This field shows scattered cells with very little cytoplasm. No clusters are present. The cells have round nuclei with a margin of cytoplasm at one side. The features appear lymphoid rather than epithelial.

40x

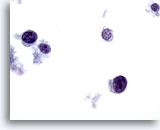

Figure 66

Breast FNA, Lymphoma. On high magnification the cells are seen to be lymphoid with a characteristic chromatin pattern. Immunocytochemical stains such as Leukocyte Common Antigen (LCA) performed on an unstained ThinPrep slide would confirm the diagnosis. 60x

Figure 66

Breast FNA, Lymphoma.

On high magnification the cells are seen to be lymphoid with a characteristic chromatin pattern. Immunocytochemical stains such as Leukocyte Common Antigen (LCA) performed on an unstained ThinPrep slide would confirm the diagnosis.

60x